.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

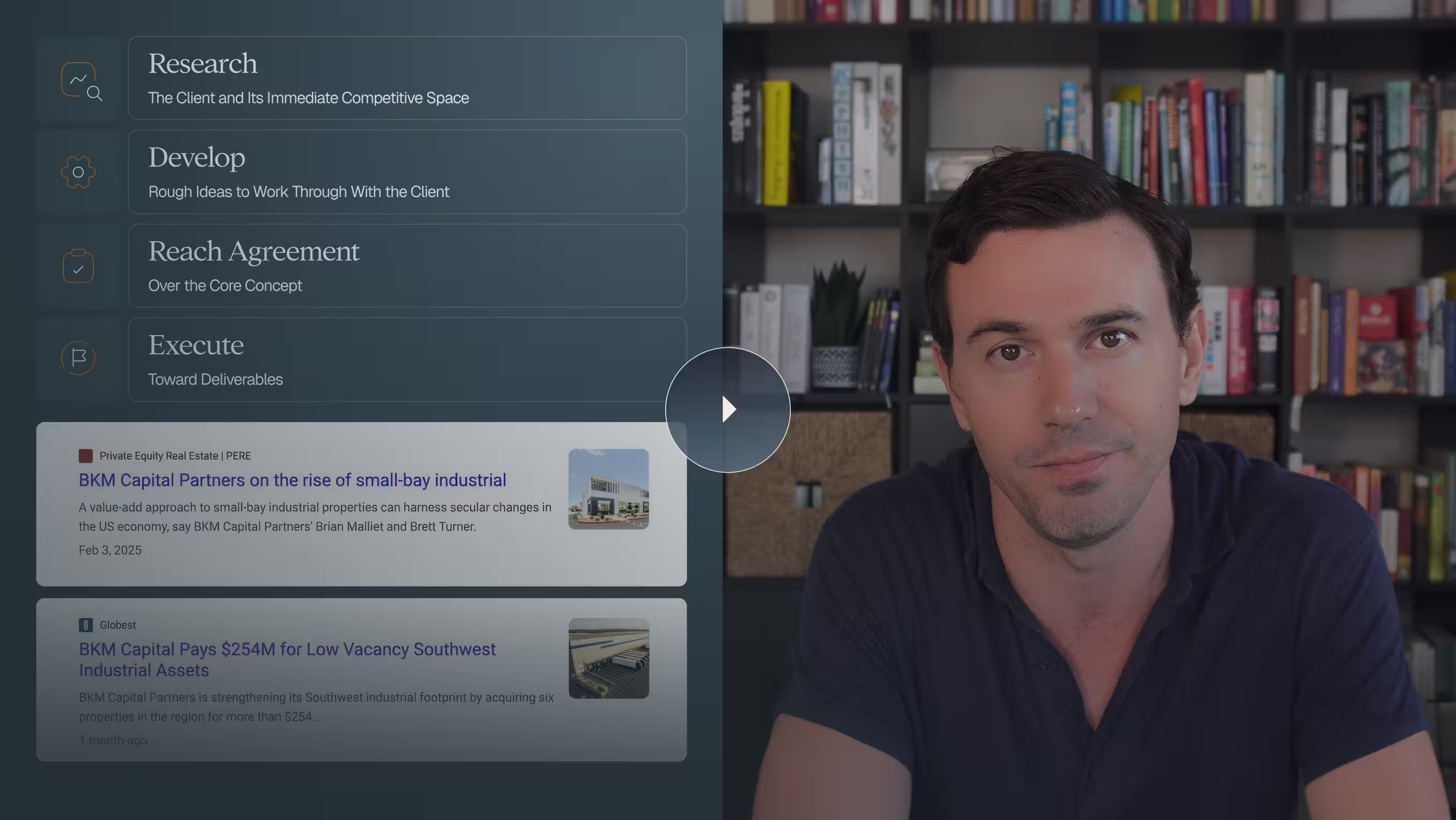

In every real estate fundraise, two core documents do most of the communication work: the pitchbook and the PPM. They sit next to each other in the diligence stack, but they serve entirely different purposes. When managers blur the lines between them — trying to make the pitchbook do the PPM’s job or vice versa — the result is almost always negative. Either the pitchbook becomes bloated and unreadable, or the PPM becomes strangely thin and incapable of supporting real diligence.

Institutional LPs don’t talk about these documents the way managers do. They’re not thinking about how many slides belong in each or which charts go where. They read both through the lens of process discipline. The pitchbook is the orientation tool: a clear guide to what the manager is doing and why. The PPM is the verification tool: the full legal and narrative record of the strategy, the risks, the governance, and the economics.

When the roles are respected, the fundraise feels coherent. When they’re not, LPs quietly question whether the manager understands how an institutional fund process works.

Below is a practical look at how the pitchbook and PPM should relate to each other — and why managers so often undermine themselves by confusing the two.

A Pitchbook Is a Story. A PPM Is an Archive.

This is the single most important distinction.

A pitchbook tells a story; a PPM documents everything that story requires.

A pitchbook is:

- short,

- skimmable,

- narrative-driven,

- focused on the decision frame,

- and designed for asynchronous reading.

A PPM is:

- long,

- comprehensive,

- legal in tone,

- compliance-heavy,

- and built to provide full, formal disclosure.

The pitchbook exists to create comprehension and interest. The PPM exists to protect both sides from misunderstanding and to satisfy the internal and external stakeholders involved in a capital commitment.

When managers try to load their pitchbook with pages from the PPM — twenty pages of macro, legal disclaimers repurposed as slide content, or highly detailed operational language — the pitchbook collapses under its own weight. Conversely, when managers attempt to use a thin PPM to “keep things simple,” LPs wonder what else might be missing.

These are not interchangeable documents. They are a narrative and its source material.

A Good Pitchbook Distills. A Good PPM Expands.

The instinct among newer managers — especially first-time fundraisers — is to treat both documents as comprehensive. They try to say everything everywhere. But institutional LPs don’t want comprehensive pitchbooks. They want coherent ones.

A strong pitchbook distills the fund’s essence into:

- the reason this asset class matters now,

- the reason this team is equipped to execute,

- the reason this strategy works in this environment,

- and the reason the LP should care.

It does not attempt to replicate all the data in the PPM. If something needs ten pages of exposition, it belongs in the PPM. If something can be communicated visually or summarized in a single slide, it belongs in the pitchbook.

One of the clearest mistakes in real estate fundraising is when managers take a consultant-written market section from the PPM (often 20–40 pages long), shrink it into tiny text, and drop it into the pitchbook. LPs don’t read it. It doesn’t persuade them. And it breaks the rhythm of the entire deck.

The pitchbook should read like a guided tour.

The PPM should read like a reference library.

LPs Don’t Confuse the Two — But They Judge Managers Who Do

LPs use pitchbooks and PPMs in different ways:

The pitchbook:

- shapes first impressions,

- structures the first meeting,

- orients the diligence process,

- and communicates the angle.

The PPM:

- supports internal memo-writing,

- provides legal grounding,

- governs compliance,

- and supplies depth where needed.

LPs know the difference instinctively. They are not confused about which document does what. But they absolutely judge managers who create ambiguous boundaries between the two.

A pitchbook cluttered with risk disclosures signals sloppiness.

A PPM missing risk disclosures signals something worse.

A pitchbook crammed with 15 pages of macro signals a lack of narrative control.

A PPM lacking macro context signals an underdeveloped thesis.

A manager who gets these wrong does not look “less institutional.” They look uncertain.

Why Too Much Detail Hurts the Pitchbook (But Helps the PPM)

Real estate managers tend to be operators at heart. They want LPs to understand the operational nuance: the property tours, the negotiation mechanics, the underwriting models, the property management efficiencies. These things do matter — but they don’t matter in the pitchbook.

Operational nuance belongs in:

- the PPM,

- the appendix,

- or the meeting itself.

When nuance overwhelms the pitchbook, LPs lose the thread. They skim, they disengage, or they mistakenly assume the strategy is more complicated than it needs to be. That’s not because complexity is inherently bad — it’s because complexity, when poorly sequenced, feels like obfuscation.

The PPM, on the other hand, is meant to absorb complexity. It is supposed to contain all the nuance, all the disclosures, all the detail that substantiate the claims in the pitchbook. It is the grounding document — dense but necessary.

The pitchbook persuades by clarity.

The PPM persuades by completeness.

Use the PPM to Protect the Manager’s Narrative Discipline

Counterintuitively, the PPM is the tool that allows the pitchbook to stay clean. When managers understand that every detail has a home — just not in the pitchbook — they feel freer to keep the deck focused. They can put the macro deep dive, the operational diagrams, and the technical nuance where they belong: in the PPM.

This is where the documents start to work together. The pitchbook sets the argument; the PPM backs it up. A well-written PPM prevents a pitchbook from ballooning into a 70-slide monster built out of fear that something might be “missing.”

One of the highest compliments LPs give — usually indirectly — is when they describe a pitchbook as “clean.” Clean does not mean simple. It means the manager had the discipline to put each piece of information in the right place.

The Pitchbook Should Be a Decision-Making Frame

The pitchbook is not the diligence. It’s the frame through which diligence flows.

A strong pitchbook answers five implicit questions:

- What is happening in the market?

- What is the strategy?

- Why this team?

- Why now?

- What will this look like in a portfolio context?

Everything else either lives in the appendix or the PPM.

When managers respect this boundary, the deck becomes a tool that LPs can use — not a burden LPs must sift through.

A pitchbook should create the motivation to read the PPM.

A PPM should validate the motivation created by the pitchbook.

Closing Thought: A Pitchbook Isn’t Short Because It’s Shallow. It’s Short Because It’s Sharp.

Real estate managers often assume that more detail equals more credibility. But institutional LPs don’t equate detail with conviction. They equate clarity with conviction. A pitchbook’s job is to make the story legible. A PPM’s job is to make the story defensible.

The separation between the two documents isn’t bureaucratic — it’s strategic.

It allows the manager to communicate the right amount of information to the right audience at the right moment in the process.

The managers who understand this distinction are the ones whose materials feel clean, confident, and genuinely institutional.

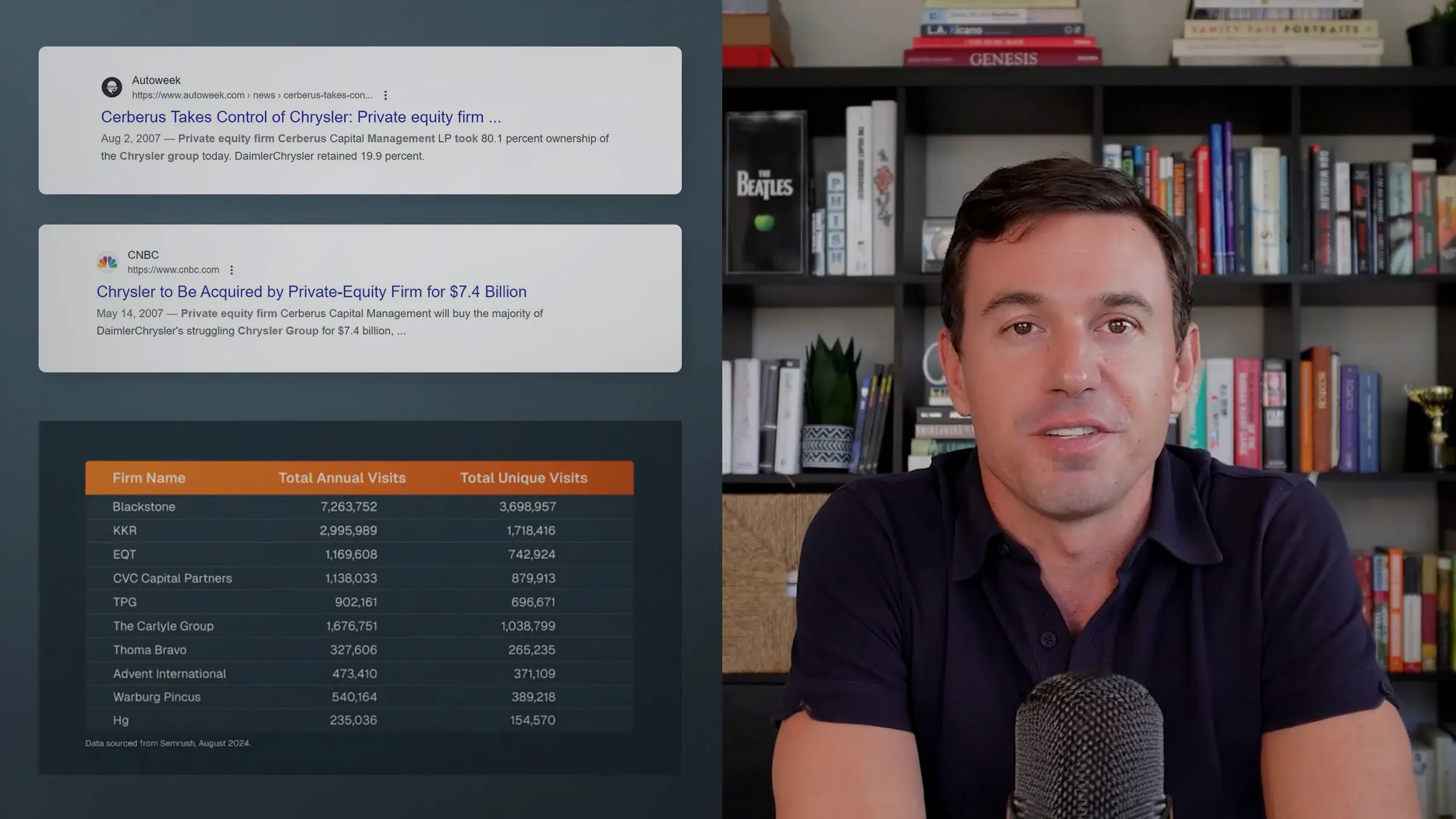

Spend enough time reviewing real estate pitchbooks and you start to see a consistent pattern: there are only two categories. Decks that look and feel institutional, and decks that don’t. And the divide has very little to do with design vocabulary or stylistic preference. It’s about the signals that design quality sends to an audience that reviews hundreds of these materials each year.

Institutional LPs don’t use the language of designers. They don’t talk about kerning or color theory. But they are exceptionally quick at making judgments about professionalism, discipline, and operational maturity. In a pitchbook, design is rarely the story — but it is always part of the psychology.

This creates a strange dynamic in real estate, a category where many managers come from operator or development backgrounds rather than allocator backgrounds. They may be excellent investors, but design is not a natural skill set. And when the pitchbook looks like a 10-year-old template or something assembled by whoever “knows PowerPoint,” LPs draw conclusions far beyond the aesthetic.

Below is a candid look at the design standards that actually matter to institutional LPs, why they matter, and how managers can present themselves with the level of polish investors instinctively expect.

Professional vs. Amateur: LPs Know the Difference Instantly

Most managers underestimate how quickly an LP can tell whether a deck was built professionally. They don’t need to identify the font or critique the color palette; they can simply feel whether the materials look and behave like institutional tools.

The most common red flag is not outdated taste — it’s dated templates. Slides that look like they came from a 2012 PowerPoint file. Generic gradients. Clipart-level icons. Mismatched shapes and colors. Charts pasted in from Excel without any reformatting. Image crops that are slightly off. A deck that looks “stitched together.”

These details may seem trivial, but they accumulate into a very clear impression:

If the manager didn’t invest in presenting their strategy cleanly, where else have they underinvested?

This reaction is not fair in every instance, but it is extremely common.

The good news is that professional design is not difficult or expensive to access. A manager doesn’t need a six-figure agency to create an institutional-grade pitchbook. They simply need someone — internal or external — who understands how to produce clean, modern slides. Someone who knows how to apply basic discipline. Someone who understands that design communicates far more than style.

Institutional Design Isn’t Ornate — It’s Clean

There is a misconception that institutional design means decorative design. In reality, institutional LPs respond to simplicity, not flair.

A premium, mature deck usually has the following characteristics:

- Clean slides with clear hierarchy.

Not walls of text, not ornamental shapes. - Charts that match the visual brand.

Not screenshots from other documents, not mismatched fonts. - Photography that is strong (or intentionally omitted).

Real estate is visual, but bad visuals hurt more than no visuals. - Consistency across slides.

Colors, spacing, image treatments, and layouts should feel coherent.

None of this requires a designer with an MFA. It requires good judgment and discipline. LPs are not looking for beauty — they are looking for maturity.

Photography: A Differentiator When Used Well, a Liability When It Isn’t

Real estate has an inherent advantage over private equity: the asset class is tangible. If the assets photograph well, photography is one of the fastest ways to build connection and credibility.

But this only works when the assets support the story. If the properties are tired, dated, or visually unappealing, showing them hurts more than it helps. Many managers underestimate this dynamic. They assume “showing the real thing” always wins. It doesn’t. LPs form impressions quickly, and mediocre imagery creates subconscious skepticism.

When the assets are strong, show them proudly. When they’re not, build a more abstract visual identity. This is one of the most important judgment calls in real estate materials — and one of the most overlooked.

Design Signals Something Deeper: Discipline

Pitchbooks do not need to be visually innovative. But they do need to be visually disciplined. Discipline is the underlying signal LPs are responding to. Clean decks imply clean thinking. Consistency suggests operational maturity. A professional visual system suggests a manager who is organized, structured, and attentive.

Messy design sends the opposite signal. LPs wonder:

- If the materials look disorganized, what does the underwriting process look like?

- If the visuals are sloppy, how tight is the property management discipline?

- If the pitchbook feels like a patchwork, what does this say about reporting?

None of these implications are necessarily accurate, but LPs make quick, subconscious leaps. In real estate especially — where operator competence is paramount — the leap is hard to avoid.

Avoid the “Broker Memo” Aesthetic at All Costs

Real estate operators often communicate using the same artifacts they use internally: deal memos, OM packets, broker marketing summaries, zoning diagrams, floor plans, maps with arrows. These materials serve a purpose inside the real estate ecosystem, but they are disastrous in fundraising.

Broker memos are dense, cluttered, and unfriendly to non-operators. They assume familiarity with local markets and deal mechanics. They make sense to someone who spends their days touring properties—not someone trying to evaluate an investment strategy across dozens of managers.

When a pitchbook resembles a broker packet, LPs silently categorize the manager as unsophisticated or underprepared. Even if the underlying strategy is compelling, the materials undermine it.

Pitchbooks must be decks, not OMs. They must feel investable, not transactional.

“Institutional Design” Does Not Require Design Vocabulary

Real estate managers sometimes worry they don’t have an eye for design, and they often don’t have a designer in-house. That’s fine. LPs are not grading aesthetic nuance—they’re grading whether the materials feel professional.

Institutional design is not:

- ornate,

- flashy,

- hyper-stylized, or

- filled with dramatic typography.

Institutional design is:

- clean,

- consistent,

- modern,

- unforced.

It is the absence of distraction.

It is the presence of coherence.

A pitchbook that feels effortless is usually the product of someone who knew what to remove, not what to add.

Use Design to Support Skimmability

LPs skim — sometimes aggressively. Good design helps them do this without missing the thread.

A skimmable pitchbook uses:

- clear, thesis-driven headlines,

- visual breathing room,

- layouts that reveal the point quickly,

- and slides that can be understood in a few seconds.

Bad design works against skimming. The eye doesn’t know where to go. Key points get buried. The hierarchy collapses. When LPs skim a messy deck, they lose the narrative — not because the story wasn’t good, but because the design didn’t help them find it.

Skimmability is not just about writing. It is about design that respects how people actually read.

Design Doesn’t Win the Mandate — But It Can Lose It

No LP commits to a fund because the pitchbook is beautiful. But LPs do walk away from managers whose materials feel amateurish or inconsistent. They don’t always say it directly, but you feel it in the lack of follow-up, the muted enthusiasm, or the subtle shift from curiosity to polite disengagement.

Design does not create conviction.

But it does create permission for conviction.

A good deck opens the door wide. A sloppy deck makes the LP second-guess whether they should step through it.

If you lined up 50 real estate pitchbooks from 50 different managers, you’d see something unsettlingly consistent: almost all of them sound the same. The phrases, the diagrams, the sequencing, even the vocabulary — much of it is interchangeable. “Vertically integrated.” “Hands-on value creation.” “Market knowledge.” “Proven team.” “Deep pipeline.” It’s no one’s fault. It’s just the gravitational pull of a category where many strategies look directionally similar.

But institutional LPs, family offices, and advisors aren’t evaluating managers as if they are equal. They are trying to understand who stands out in a category that often doesn’t differentiate itself. A pitchbook that reads like everyone else’s isn’t neutral — it’s negative. If everything sounds the same, the LP assumes (fairly or unfairly) that nothing is distinctive about the manager.

Differentiation in real estate is rarely about inventing a new vocabulary. It’s almost always about going one level deeper — past the surface-level language that everyone uses and into the underlying mechanics, culture, or track record that actually separates one firm from another.

Below is a practical look at how real estate managers can create pitchbooks that actually sound like them — not like a template the last ten managers used.

Start From the Assumption That You Sound Like Everyone Else

This may feel harsh, but it’s the most liberating starting point. Most real estate managers begin the pitchbook process from the wrong mental model: “Here’s what makes us different.” The problem is that many managers have very similar backgrounds, similar strategies, similar asset types, and similar processes. When the strategic DNA is similar, the language almost always converges unless you actively intervene.

So the better starting question is:

“What could we say that 50 other firms can’t?”

Sometimes the answer is clear — unusual experience, an uncommon geographic footprint, a distinct sourcing method, or a market thesis that isn’t mainstream. Sometimes it’s more subtle — cultural DNA, a founding story, or a pattern of performance that tells a story other firms can’t replicate. And sometimes it’s not obvious until you dig: a specific operational capability, a technique in underwriting, a data-driven wrinkle, or some aspect of the team’s history that is quietly powerful.

You don’t need dozens of differentiators. You need one or two that are real and defensible. The pitchbook’s job is to elevate those above the noise.

The Best Differentiators Translate Strategy Into Investor Outcomes

This is one of the clearest gaps you identified: real estate managers often talk about their strategies in inward-facing terms. They describe what they do instead of what those actions mean for the investor. Operators, in particular, fall into this trap because they’re so used to speaking to lenders, brokers, developers, or other operators who already understand the mechanics.

Institutional LPs are reading for something different. They want to understand how your specific approach delivers outcomes that differ from the market’s baseline. They’re not trying to become experts in your process; they’re trying to understand the effect of your process on risk, return, and portfolio construction.

So instead of:

- “We are vertically integrated,”

try: - “Because our property management is in-house, we compress the timeline between operational issues and corrective action.”

Instead of:

- “We use a hands-on approach,”

try: - “Our team’s background in X–Y–Z enables faster improvements in NOI during the first 18 months of ownership.”

Instead of:

- “We have strong local relationships,”

try: - “We see off-market deals earlier, which affects both pricing and competitive posture.”

These are small shifts — but they change the deck from a list of internal competencies to a list of investor-relevant outcomes.

Make the Executive Summary Do the Hard Work

Differentiation usually succeeds or fails in the first two pages of a pitchbook. This is where institutional LPs begin to decide what your three “memorable things” are. If you don’t choose those for them, they choose for themselves — and the default choices are rarely flattering.

A strong executive summary:

- isolates the one or two differentiators that matter most,

- presents them directly, not buried inside paragraphs,

- ties them to the market context,

- and gives the reader a reason to care before they slog through the details.

For later-vintage managers, the summary must convey credibility and continuity. For first-time or second-time managers, it must convey legitimacy. For managers in crowded categories, it must convey a difference. For managers in emerging niches, it must convey investability.

The supporting slides can carry nuance. The opening slide must carry memory.

Property Images Aren’t Decoration — They’re Differentiation Tools

Real estate has one built-in advantage over private equity: tangibility. LPs can see what you're investing in. They can imagine themselves standing in front of the assets. The more the asset class lends itself to visual connection — industrial, multifamily, hospitality, office conversions — the more important it is to use that to your advantage.

But the rule is simple: If the assets photograph well, use them. If they don’t, don’t.

Few things undermine a pitchbook faster than mediocre images of mediocre assets. If your assets don’t elevate the brand, the visuals should become more abstract and more brand-led.

When the imagery is strong, it creates instant connection. When it isn’t, it creates doubt.

Understand What Differentiation Actually Looks Like to LPs

Differentiation is not about unusual vocabulary. It’s about unusual clarity.

LPs skim. They flip. They search for the thread that feels most real. They have a decade of experience with managers claiming the same things. And they’re trying to determine whether your story has any internal friction, any mismatches, or any false notes.

Differentiation sounds like:

- a market thesis that isn’t recycled,

- a sourcing angle others can’t plausibly claim,

- performance patterns that actually match the stated strategy,

- geographic focus that feels intentional instead of generic,

- or a firm history that creates a coherent narrative arc.

You don’t need all of these. You need one or two. But they must be hard-edged and specific, not vague or interchangeable.

The job of the pitchbook is to help the LP find that specificity without digging.

Differentiate by Restraint, Not Excess

One of the fastest ways to undermine differentiation is by overwhelming the reader with detail. Real differentiation requires editing. The pitchbook should avoid three common traps:

- Process bloat. Too many diagrams, too many arrows, too many bullet points.

- Market-section overreach. Macro is important, but 20 slides of macro overwhelm the story.

- Overuse of jargon. Some LPs know the category deeply—but many don’t want to decode technical language while skimming.

Great pitchbooks feel intentional. They show the manager understands not only what makes the strategy work but how to communicate it without drowning the reader.

The Most Important Differentiator: A Coherent Angle

Every manager has a story. The problem is that most stories are told indirectly or inconsistently. A differentiated pitchbook has an angle — a point of view that shapes the entire narrative.

That angle might be:

- a market dislocation the manager understands better than peers,

- a sourcing method that consistently uncovers mispriced assets,

- a capability gap the team fills uniquely well,

- or a long history of execution in a niche others find too small or too complex.

Whatever the angle is, it must be explicit. LPs cannot intuit it from between the lines. The pitchbook must introduce it early, reinforce it through the structure, and land it again at the close.

When the story is clear, differentiation feels effortless. When the story is fuzzy, everything sounds generic.

Closing Thought: Differentiation Lives in the Details LPs Actually Remember

Institutional LPs see hundreds of pitchbooks. They are not impressed by ornate phrasing or unusual adjectives. They don’t need a brand-new vocabulary. They read for coherence, confidence, and specificity. They want to know what is genuinely yours and why it matters.

Differentiation in real estate is about finding the one or two things that no one else in the room can plausibly claim — and building the pitchbook around them. Not loudly, not theatrically, but with enough clarity that the LP walks away remembering exactly why the manager matters.

That is the real work of differentiation.

Real estate fundraising sits in a strange middle space. Institutional LPs know the asset class well enough to read materials quickly, but the category is specialized enough that structure, clarity, and rhythm matter. And unlike private equity — where most pitchbooks are built for one uniform audience — real estate fundraising spans a range of sophistication and context. When we focus on institutional LPs, though, the patterns become clearer. They’re not monolithic, but the way they consume and evaluate pitchbooks follows certain familiar cues.

The best real estate pitchbooks understand these cues instinctively. They don’t drown the reader. They don’t hide the angle. They move in a sequence that institutional LPs immediately recognize. And they avoid the structural mistakes that quietly cause managers to lose credibility long before the in-person meeting.

Below is a practical view of how institutional LPs read pitchbooks — and how managers can structure them in a way that actually supports the fundraising process.

Start With the Market, Not the Manager

In most cases, a real estate pitchbook should begin with the market overview. It’s not because LPs care more about macro than management — it’s because real estate is cyclical, contextual, and timing-sensitive. A strategy is only understandable inside the environment it intends to exploit.

A pitchbook that opens with team bios or process flows puts the cart before the horse. LPs want to understand the setting before they evaluate the characters and plot. When the first few slides frame the macro landscape clearly — where we are in the cycle, why this property type matters now, what’s shifting in supply, demand, and valuation — the audience is better prepared to understand the strategy itself. Without this groundwork, everything that follows floats in abstraction.

For most managers, the right length for this section is surprisingly modest: a handful of well-curated exhibits, 3–4 moderately dense slides or 6–8 streamlined ones. Enough to establish conviction, but not enough to test patience. LPs see hundreds of these decks every year; they know instantly when a manager has a real view of the landscape versus repeating recycled talking points.

Strategy Comes Next — The “Plot” of the Narrative

Once the stage is set, the strategy becomes the plot. This is where managers explain how they source, how they buy, how they create value, and how they think about portfolio construction. In most real estate shops, this is the content the team knows best. The challenge is not expertise — it’s discipline.

Real estate managers often overload the strategy section because they’re trying to anticipate every possible question. But institutional LPs already understand the mechanics of sourcing and asset management at a high level. They don’t need elaborate process diagrams unless the strategy is genuinely esoteric or unusually complex. In those edge cases—heavy data-driven sourcing, a vertically integrated structure that needs unpacking, or strategies where the workflow is itself the differentiator — a dedicated process section makes sense. For the majority of managers, it adds weight without adding clarity.

A good strategy section shows how the manager thinks. A bad one overwhelms the reader with detail that belongs in a PPM.

Team Belongs at the End — Not the Beginning

One of the most consistent structural errors in real estate decks is putting the team among the first ten slides. It’s intuitive but counterproductive. When an LP doesn’t yet understand the market context or the strategy, a wall of headshots and credentials communicates nothing. In many decks, the biographies feel like a collection of résumés in search of a story.

Once the reader understands what the strategy is, the team suddenly matters. The person running construction oversight becomes relevant once the deck explains why construction is central to value creation. The CIO’s background becomes meaningful once the market thesis is established. Context turns credentials into comprehension. Without context, it’s just noise.

This is especially important because most LPs read decks asynchronously. They’re flipping through a PDF alone at their desk, not listening to a founder walk them through slide by slide. Putting the team early forces them to evaluate people without understanding why those people are important. Putting the team later creates narrative coherence.

The Executive Summary Is Often the Weakest Slide

Ironically, the most important slide in a pitchbook is often the worst one. Many executive summaries are overstuffed, cluttered, or so generic that they might as well belong to any manager in the category.

This is a costly mistake. After a first meeting with a new manager, most LPs will remember three things, maybe fewer. The executive summary should define those things and shape the way the LP reads the entire deck.

What those three things are depends on the firm’s position in the market. Later-vintage managers need to convey consistency and momentum. Newer managers need to establish legitimacy. Crowded sectors demand sharp differentiation. And newer asset classes require the manager to make the category feel both investable and compelling.

A good executive summary makes decisions for the reader. A weak one makes the reader work too hard.

Why “Broker Memo” Style Decks Undermine Institutional Credibility

Many real estate managers come from operator backgrounds. Their instincts are shaped by property-level work, not allocator-level communication. This often leads to pitchbooks that resemble broker packages — dense maps, zoning diagrams, aerials, interior unit photos, and slide after slide of operational detail.

Broker memos are designed for real estate professionals, not LPs. They present information without hierarchy because the audience already understands how to interpret it. Pitchbooks serve a different purpose. They need to create a structured, digestible narrative that makes sense to someone who is not inside the day-to-day mechanics of the asset class.

When a pitchbook looks like a broker memo, LPs quietly assume the manager has underinvested not only in design, but in communication — and perhaps in organizational discipline more broadly. It lands more harshly than managers expect.

Design Still Matters — A Lot

Institutional LPs don’t speak in design vocabulary, but they recognize design quality instantly. They know when a deck was built by a professional versus someone in-house who “knows PowerPoint.” And because LPs review hundreds of decks per year, they form impressions rapidly.

Good design is not ornamentation. It’s a trust signal. It conveys discipline, attention to detail, and coherence across the organization. In real estate specifically, photography, geography, and cycle clarity matter more than in private equity, because the asset class is tangible and has deep visual context. When the photography is strong, use it. When it isn’t, leave it out. Mediocre images dilute professionalism.

The Pitchbook’s Real Role in Diligence

Managers often underestimate how widely a pitchbook circulates inside an LP organization. It shapes the first impression. It structures the first meeting. Analysts use it when preparing memos. Committee members skim it to understand the argument. It becomes the artifact that survives the pitch long after the meeting has ended.

In other words, the pitchbook is not just a marketing document. It is an internal selling tool — for people the manager may never meet.

That alone should change how managers think about structure and clarity.

LPs Skim, So Skimmability Dictates Success

Most LPs will not read every slide. They skim. They read headlines. They look for structure. They want to understand the logic quickly. They don’t want to decode a complicated layout. The more skimmable the deck, the more likely it is to be understood — and the more likely the manager is to get a second meeting.

It’s tempting to think that LPs will sit with a pitchbook and absorb it like a case study. They won’t. The attention economy has changed the way everyone reads. Pitchbooks must adapt. Clarity wins.

Clarity Beats Complexity

Institutional LPs don’t need to be dazzled. They need to be oriented. They need a coherent structure. They need a sense of momentum, logic, and organizational maturity. When the deck’s structure supports the argument — and not the other way around — LPs stay with you. When the story is clear, the reader remembers the right things.

That is the difference between materials that look institutional — and materials that are institutional.

Real estate managers often underestimate how many different types of visitors arrive on their website. Institutional LPs, family offices, RIAs and advisors, high-net-worth individuals, and transaction audiences all come with different goals, levels of sophistication, and expectations. Most managers try to accommodate everyone at once and end up appealing to no one in particular.

The good news is that you don’t need separate sites for separate audiences unless you’re running substantially different vehicles (such as a private equity-style fund alongside a retail product). For most firms, the website should perform a simpler job: tell a coherent story, do so professionally, and make it easy for each audience to find what they came for.

Every category of investor ultimately wants the same three things: credibility, clarity, and a story that holds together. The differences between audiences are real, but they mostly affect framing, not content. When the core story is strong, everyone can follow it.

Everyone Is Looking for the Same Signal First: Credibility

Sophisticated LPs, entrepreneurial family offices, RIAs advising end-clients — all of them approach an unfamiliar manager’s website with a similar question:

“Do these people look legitimate?”

They’re making a judgment call before they ever study the strategy. The impressions they form come from things as simple as:

- clarity of language

- a clean, modern layout

- consistent visual identity

- current information

- evidence that the firm knows how to present itself

None of this requires a large team. It requires a coherent story and a website that isn’t fighting against it.

If the site can communicate competence and professionalism quickly, most audiences will give the manager a longer look. If it can’t, very few will.

Institutions, Family Offices, and Advisors Aren’t Looking for Separate Stories — Just Different Emphases

Institutional LPs are methodical. They’re looking for the scaffolding: strategy, team, track record, and organizational discipline. They want to understand the architecture of the firm before anything else.

Family offices often move more fluidly. They care about the same fundamentals, but they may respond more quickly to specificity — an unusual niche, a unique sourcing advantage, a philosophy they can intuitively connect to. They are sometimes more open to off-the-run strategies, and a well-articulated story can matter as much as scale.

RIAs and advisors occupy a different place entirely. They’re intermediaries. Their job is to retell the story to end-clients in plain language. Anything that feels overly technical, crowded, or loaded with industry jargon makes the downstream communication harder. Their bar is: “Can I take what I’m seeing here and explain it faithfully to someone else?”

High-net-worth individuals, when they arrive directly, behave the way any consumer behaves online: they skim. They glance at the visuals. They look for the one idea that tells them who you are. They are, in many cases, responding emotionally before anything else.

But none of these groups needs a different version of the truth. They simply need the truth arranged cleanly, without noise, and without excess complexity.

Why Trying to Speak to Every Audience Simultaneously Usually Fails

The biggest mistake firms make is assuming they must announce themselves to each audience on the homepage. That instinct almost always produces a jumble of competing statements — one line written for institutions, another for advisors, another for HNW, all stacked in a way that forces the visitor to decode the hierarchy themselves.

If you feel tempted to add qualifying lines like “for institutional and high-net-worth investors,” the problem is not the audience — it’s the structure.

A well-built real estate website does not require three or four parallel messages. It requires a single, durable narrative that explains:

- what the firm does,

- how it creates value, and

- why its approach is credible.

Different audiences will take what they need from that core narrative. If you need to support multiple vehicles — for example, a private real estate fund and a non-traded REIT — those should be separated structurally (as distinct pages or microsites), not blended at the homepage.

Starwood and Blackstone are both examples of firms that maintain a unified parent brand while supporting multiple audience types. Their sites do not try to speak to each audience individually; they simply maintain enough clarity and hierarchy for each visitor to find their lane quickly.

Navigation and Structure Are What Make Multi-Audience Storytelling Possible

If you do need to support several audience types, navigation does almost all of the work. The site should route each group toward what they came for without forcing them to absorb everything else.

Clean top-level structure — strategy, portfolio, team, and fund pages — allows visitors to self-select. Advisors know where to look. Institutions know where to dive deeper. High-net-worth visitors can orient themselves immediately. No one is overwhelmed.

Any site that needs a modal pop-up asking, “Are you an institutional investor, a high-net-worth investor, or a retail investor?” is actually telling you something else: the firm needs different websites, or at least different sub-sites, for fundamentally different products.

Most firms don’t operate in that world. Most firms need a single site that is simply structured well.

A Strong Core Story Solves Most Multi-Audience Problems

When a firm has a clear definition of what it does and a point of view that sits above the cycle, the rest becomes much easier. Investors remember only a few things after an initial meeting — perhaps two or three ideas at most. A website should work the same way. It should frame the story in a way that is natural to repeat.

The nuances of how that story is received vary by audience, but the underlying narrative doesn’t need to. High-net-worth investors may connect more quickly through emotion; institutions through structure; advisors through clarity. But they’re all deciding whether the manager seems credible, organized, and intentional.

A website that expresses those qualities cleanly — without trying to be all things to all people — stands out in a category where very few firms tell their story well.

Most real estate websites do not look institutional. They look like developer sites, or property manager sites, or small-business sites that have been lightly reskinned for the investment world. The gap isn’t just aesthetic — it’s a credibility gap. When a manager is unknown to an investor, much of the early evaluation happens through the website, and investors immediately sense whether a firm is operating at a high level or improvising.

What separates an institutional-quality website from everything else is not a specific color, or a specific typeface, or a specific layout pattern. It is the underlying quality of the design. And quality, in this space, is largely about clarity, restraint, spacing, and a point of view that feels considered rather than thrown together.

Real estate managers often want their website to communicate seriousness and sophistication. But many unintentionally communicate the opposite — not because they lack real institutional capability, but because the website carries visual cues that drift more toward “developer marketing collateral” than “investment manager.”

Getting this right matters. The website sets the tone for every other communication an investor will see.

Institutional Quality Is Not About a Specific Look — It’s About Execution

There is no single “institutional aesthetic.” Hines uses deep crimson, a color many investment managers would avoid entirely, and still delivers one of the strongest brand experiences in the industry. Blackstone and Starwood lean heavily on dark palettes and bold typography. Others take a lighter, more editorial approach.

Institutional quality comes from execution, not conformity. Good websites feel:

- properly spaced

- thoughtfully structured

- quiet rather than busy

- modern without being trendy

- confident without overstatement

The real test is simple: does the site feel like something built by design professionals who understand both the category and the audience? An investor senses the answer immediately.

Clients often want a rulebook — “which colors signal institutional?” or “which fonts should we avoid?” — but these questions miss the point. Institutional is not a style. It is a standard.

The Structure That Supports an Institutional Brand

Nearly every real estate manager ends up with a similar macro structure, because the structure reflects how investors look for information. The website should feel intuitive, even predictable, while still expressing a distinct identity.

A clean layout usually looks something like:

Homepage → About/Approach → Portfolio → Team → Insights (or News) → Contact

Managers can name these sections however they want — “Strategy,” “Platform,” “History,” “Organization,” “What We Do” — but the underlying logic should remain: the homepage as a precise summary of the firm, followed by a more detailed explanation of the strategy, then proof (the portfolio), then the people behind it.

Insights is optional, but increasingly valuable. Even a small body of content signals a level of thoughtfulness and engagement that most managers, frankly, do not invest in.

What matters most is that the structure feels effortless. The investor should never need to think about where to click next.

The Portfolio Section: Where Most Institutional Websites Break Down

Investors nearly always check the portfolio page, even if they are only preliminarily curious. And this is where many real estate websites feel the weakest.

A shallow grid with property photos and addresses tells an investor very little. It is a necessary catalog, but not a differentiator. Institutional-quality portfolio pages offer more texture: how the firm creates value, what the manager actually does to improve assets, what themes emerge across the portfolio, and where the team has repeatable competence.

This does not mean every firm needs 15 case studies, or a fully cinematic presentation. It simply means the portfolio should reflect more than ownership — it should convey capability.

If the firm lacks a deep portfolio, that is fine. Many emerging managers do. In those cases, the website should emphasize clarity, conviction, and strategy rather than trying to inflate limited history. Investors can sense when a manager is authentic about its stage of growth versus when it is trying to fill space.

How a Website Conveys “Modern” Without Chasing Trends

Website modernity is often misinterpreted. It’s not about futuristic animations or elaborate effects. A modern site is simply one that feels fresh, intentional, and current.

Older sites look older because they are older — their spacing is tight, their grids are uneven, their images are low-resolution, and their copy reflects another era. You can feel the age.

A modern site, by contrast, gives the impression of space and clarity. Text breathes. Images are crisp. The homepage feels composed, not crowded. Messaging is distilled rather than padded. And the site performs well on mobile, which is still surprisingly rare in the real estate category.

You do not need a radical design concept to look institutional. You need a clean design executed at a high level.

Why These Details Matter for Investors

Investors do not evaluate websites the way designers do. They don’t analyze grids, compare typefaces, or debate color theory. They sense whether the site works, and that sense becomes a proxy for the manager’s internal organization.

A site that is clean, modern, and coherent gives the impression of a firm that operates the same way. A site that is cluttered, dated, or generic suggests the opposite. Investors may not articulate this explicitly, but the inference happens quickly.

The website also shapes the “mental model” through which investors interpret downstream materials. A pitchbook that matches a strong website feels stronger. The same pitchbook, paired with a weak website, feels diminished. Consistency matters more than most managers realize.

The Opportunity for Managers Who Get This Right

When most real estate firms still rely on dated sites that feel more like developer brochures than institutional brands, any manager who commits to clarity and quality stands out immediately. Investors make up their minds quickly. A website that communicates competence and intentionality — without grandiosity or generic claims — earns a second look.

Institutional investors, family offices, RIAs, and HNW individuals may approach the category differently, but they share one expectation: they want to feel confident in who they’re dealing with. A strong website makes that confidence easier.

In a space where few firms do this well, the gap between “fine” and “excellent” is far wider than most managers think.