.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

A real estate manager's website isn’t just another marketing asset. It quietly becomes the anchor of the entire visual brand. It defines the look, feel, and tone of everything else the firm produces — pitchbooks, quarterly updates, advisor materials, deal announcements, and even LinkedIn posts.

Most firms don’t choose this dynamic intentionally. It happens because the website is the one artifact that lasts the longest, reaches the widest audience, and is the hardest to change. Whether the firm realizes it or not, the website becomes the foundation upon which all future storytelling sits.

Why the Website Ends Up Becoming the Anchor

Real estate managers seldom rebuild their sites more than once every five to seven years. In some cases, it’s much longer. Few firms have dedicated marketing staff; the website becomes an occasional project handled by an IR professional, a CEO, or an outside partner during quieter periods. As a result, the decisions made during a redesign tend to persist far longer than anyone expects.

This longevity gives the website an outsized influence on the rest of the brand system.

Everything else must harmonize with it — not because of dogma, but because investors implicitly expect consistency.

A pitchbook may change with every fund.

Quarterly reporting updates four times a year.

Marketing documents evolve as the story evolves.

But the website remains.

Firms often don’t realize how much they’re depending on it until they’ve lived with a weak one for seven years.

The First 10–30 Seconds: What a Visitor Must Feel

Most people who visit a real estate website aren’t browsing. They’re assessing. In the first half-minute, the site needs to deliver a simple, confident impression:

- This manager is competent.

- This manager is professional.

- This manager has a clear identity.

- This manager has nothing messy or improvised hiding in the margins.

It also needs to be easy to use.

If someone arrives only to find a bio or check the portfolio, there should be zero friction. Navigation is a credibility signal in its own right.

What you want to avoid is the opposite: muddled messaging, dated visuals, generic statements, or anything that feels improvised. When a site is an 8 instead of a 9 or 10, investors feel it.

The Website Defines the Visual System for Everything Else

Pitchbooks, quarterly letters, updates, fact sheets — these materials all inherit the design logic of the website. Even within the constraints of PowerPoint, a designer can echo the website’s typography, spacing, color palette, tone, and layout rhythm. Professional investors notice when materials feel like part of the same system, even if they can’t articulate why.

Consistency creates familiarity.

Familiarity creates trust.

Trust creates ease.

The website doesn’t need to match everything perfectly — PowerPoint will never offer the same palette — but it must establish a system that downstream materials can follow. When that system is missing, every subsequent asset feels a little more improvised.

Permanence vs. an Evolving Market

Real estate cycles are fast-moving. Property types fall in and out of favor. Interest rates reshape the entire logic of value creation. Managers sometimes worry that their website will become outdated as the market turns.

It shouldn’t — at least not the parts that matter.

Core pages should be built around enduring truths: what the firm does, why its strategy makes sense, who leads it, and how it creates value. These elements shouldn’t change every time the Fed moves. If they do, the brand strategy was too tied to a moment in time.

Market commentary belongs elsewhere — in the Insights section, in letters, in articles.

The website is the permanent structure.

Content is the flexible layer that sits on top of it.

Real shifts to the website usually come from product expansion, not macro change. When a firm launches additional funds or new investment vehicles, the site must accommodate those additions cleanly. That’s where thoughtful structure matters.

What a Website Can Express That a Pitchbook Never Will

Unlike pitchbooks — which are linear, static, and fundamentally instructional — a website can create an experience. Motion, transitions, video, spacing, and interactivity all contribute to a sense of calm, intentionality, and sophistication.

A website also offers depth. Someone can skim the homepage and immediately understand the basics, but someone else can dive deeper into narrative, background, market rationale, team philosophy, or thought leadership. It accommodates both types of visitors without forcing either into the wrong path.

And increasingly, websites do something else:

They communicate with machines — search engines, LLMs, and discovery algorithms. A structured, technically sound, well-written site will surface more often, influence more decisions, and widen the top of the funnel. A weak one remains invisible.

The Quiet Constant That Shapes Everything Else

In real estate — where cycles shift, investment vehicles expand, and materials evolve — the website is the quiet constant. It holds the brand system together. It sets the tone for every first impression. It becomes the reference point for every subsequent deck, document, and digital touchpoint.

When it is strong, the rest of the communication ecosystem has somewhere solid to stand. When it is weak, everything downstream gets harder than it should be.

A website is not simply a digital brochure.It is the chassis on which the entire brand sits.

Real Estate Has the Widest Investor Universe of Any Asset Class You Serve

Unlike private equity, where the audience is unusually clean — management teams, sellers, and institutional LPs — real estate fundraising crosses a far larger and more varied spectrum. A single real estate manager might engage with pension funds, family offices, the wealth channel, HNW individuals, retail investors, or all of the above.

And although these groups often get discussed as though they’re monolithic, the reality is more nuanced. They differ in decision-making processes, risk orientation, communication preferences, and the way they interpret brand signals.

This is why real estate messaging can feel harder to calibrate than other asset classes. The audience is broader, the motivations are more varied, and the distribution channels influence how much information investors even see.

In most cases, the firms that succeed across multiple audiences are the ones that tailor the narrative appropriately — not by changing the fundamentals, but by understanding how each audience consumes information and what they look for early in the process.

Institutional LPs: Process, Preparation, and Pattern Recognition

Institutional LPs are often portrayed as uniformly risk-averse, but the truth is more complex. Some institutions are extremely sophisticated, comfortable with contrarian ideas, and willing to back new managers early. Others operate in rigid governance structures designed to avoid surprises.

Broadly speaking, institutional LPs look for three things immediately:

1. Process discipline

The materials must match the internal workflow these LPs use to evaluate managers. They want clarity, structure, and documentation that fits into their comparative frameworks.

Pitchbooks must be organized. DDQs must be complete. Data rooms must be navigable. Visual inconsistency across documents is interpreted as operational inconsistency.

2. Organizational maturity

Most institutions rely on teams of employees who are accountable for avoiding disaster more than capturing outlier upside. That means they look closely at the cues that signal readiness:

- consistency across brand and materials

- coherence in narrative structure

- clarity around strategy

- clean digital presence

- unified formatting and labeling

The majority of institutions judge readiness by how a manager presents themselves — because it’s the best early proxy for how they operate.

3. Contextualization of team and track record

Institutions want to understand the people behind the strategy and how they interpret the market. They will eventually scrutinize performance in detail through Preqin, consultant databases, or internal analytics. But early on, they want a well-packaged, well-argued rationale for why the strategy deserves their time.

For managers who are transitioning from syndicating deals to raising commingled funds, this is a ten-year journey in most cases. Only a small fraction complete it. Institutions “weed out” the underprepared with the same quiet rigor that medical schools use to filter pre-med majors — not intentionally, but through the sheer demands of discipline and consistency.

Family Offices: The Most Heterogeneous Audience of All

Family offices sit on the opposite end of the spectrum from institutions. They vary widely in sophistication, structure, and worldview. Some are led by deeply experienced CIOs with institutional backgrounds. Others are run by a handful of principals who make decisions based on intuition, relationship, or personal interest.

Yet, in most cases, a few consistent patterns emerge.

1. They respond to specificity

Family offices often gravitate toward managers who can articulate a clear angle. They want to understand what is interesting about the opportunity, what makes it distinct, and why it fits with the family’s worldview or personal interests.

This is why unique or story-rich strategies — ranchland, farmland, hospitality, niche industrial, redevelopment — can resonate strongly.

2. They react well to polished identity — as long as it’s not corporate wallpaper

Family offices don’t mind polish. In many cases, they appreciate it. But they’re turned off by generic, flavorless “big-company” branding. They prefer identity that feels deliberate and confident, not institutional sameness.

3. They move faster than institutions — usually

A meaningful share of family offices operate without committee structures. The CIO and principals can make a decision after a single meeting, provided the opportunity resonates.

The flip side: if the story feels overcomplicated, jargon-heavy, or indistinct, they disengage just as quickly.

High-Net-Worth Investors: Emotion, Simplicity, and Advisor Influence

HNW individuals span an even wider behavioral spectrum than family offices. Some are cautious. Some are adventurous. Many rely entirely on intermediaries. But as a pattern, a few things hold:

1. Emotional resonance matters

HNW investors often invest in what feels familiar or appealing. Ranchland. Storage. Hospitality. Land. These categories display identity and narrative texture that institutional strategies often mute.

The best analogy is consumer vs. B2B private equity: when someone recognizes a skincare brand they personally use, it creates rapport. Real estate has similar “identity hooks” that matter far more to individuals than institutions.

2. They frequently misunderstand fund mechanics

Not because they are unsophisticated — but because the distribution channels give them incomplete information.

Most HNW allocations are shaped by intermediaries:

- RIAs

- wealth managers

- advisory platforms

These professionals are often limited to the products available on their platform. They work with curated menus from major managers. They rely on summary sheets, not full decks. They are not evaluating the market; they are navigating the options they’re permitted to present.

This is where DG’s clarity-first approach becomes critical: simple, clean, high-level communication that assumes less insider context.

3. Materials are drastically shorter

Individuals are rarely looking at full pitchbooks. They are looking at disclosure-heavy 2–4 page summaries that must do a lot with very little real estate.

RIAs and Wealth Advisors: Clarity Dominates Everything

For advisors, the question is almost always:

“Will this blow up on me?”

The majority of advisors are judged on:

- stability

- client satisfaction

- minimizing disasters

They care more about clarity, simplicity, and trust signals than deep detail.

Brand name matters disproportionately.

When the manager is not a household name, advisors need reassurance through:

- clean branding

- modern design

- straightforward strategy framing

- explicit risk language

- extreme succinctness

Microsites, minimalistic layouts, and simple language matter far more in this channel than in institutional fundraising.

Retail Vehicles: Trust, Simplicity, and Professional Restraint

Non-traded REITs, interval funds, Reg A offerings — these sit at the retail end of the spectrum.

In most cases, what works here is:

1. Professionalism above all else

Extreme clarity. Conservative tone. Clean presentation. No hype.

2. Simplicity as a design principle

Retail vehicles require heavy disclosures. Space is limited. Messaging must be distilled to essentials: what the fund is, what the fund does, and why it is structured the way it is.

3. Brand name as the anchor of trust

Starwood’s retail products work because the parent brand carries enormous weight. Smaller managers entering this channel face a steeper climb and must rely on design, clarity, and alignment with credible partners.

The Biggest Mistake: Trying to Speak to All Audiences at Once

Many managers assume they can build one website, one deck, and one set of materials that simultaneously serves:

- institutions

- family offices

- RIAs

- HNW individuals

- retail investors

This is the most consistent failure point.

Different investor types require different:

- depth

- tone

- sophistication

- structure

- compliance

- visual design

- messaging arcs

In general, the cleanest architecture is:

Parent website = institutional

Modern, strategic, thesis-forward.

Wealth/retail products = separate microsites

Distinct, simple, disclosure-aligned, clarity-first.

Trying to merge these in one place dilutes both.

What Stays Constant Across Audiences

Despite the variation, a few fundamentals apply everywhere:

- clarity always matters

- a clean website always signals maturity

- coherence across materials signals operational discipline

- a clear thesis always beats generic language

- consistency across visuals signals that the manager has their act together

Investors can differ, but confusion turns everyone away.

Why This Matters for Real Estate Managers

Real estate is unique in that a single platform can attract billion-dollar institutional allocations and $50k checks from individuals.

This range is an advantage — but only if the manager understands how to adjust the story, not abandon it.

The strongest brands in real estate are the ones who express the same strategy in different ways to different audiences. Not by hiding detail, not by spinning narratives, but by respecting the reality that investors evaluate opportunities through very different lenses.

And in a category as crowded and cyclical as real estate, that nuance becomes one of the few true differentiators a manager can control.

Most Real Estate Managers Don’t Realize They’re Sending Developer Signals

Real estate is a category where language and visuals often blur between sub-industries. Many managers come from development backgrounds — construction, entitlements, leasing, project management — and their early instincts around presentation tend to mirror that history.

The problem is simple: when a real estate investment manager unintentionally looks like a developer, LPs assume the manager takes developer-like risk, even if the strategy is purely income-oriented or value-add.

This is not about sophistication or prestige. It is about category misclassification. When the visual identity sends the wrong cues, LPs start evaluating the manager through the wrong mental model.

What Developer Branding Typically Signals

LPs associate developer aesthetics with specific types of risk:

- entitlement and zoning uncertainty

- ground-up construction

- unpredictable timing

- project-level volatility

- heavy capex cycles

- execution risk that can’t be diversified away

These exposures are perfectly reasonable in the right fund — opportunistic, higher-return profiles — but they are not what most LPs want in a core, core-plus, or even traditional value-add mandate.

A firm may not touch development risk at all, but if the brand looks like an offering memorandum for a specific building, the impression is already set.

How Real Estate Managers Accidentally Look Like Developers

Most mis-signaling falls into a handful of patterns.

1. Leading with property photos instead of strategy

Full-bleed photos of single assets immediately create the sense of a project-specific pitch. LPs assume the firm is pushing a deal, not a strategy.

2. Using overly literal or interior-heavy photography

Developers showcase finishes, materials, and design details. Investors should not. Interiors signal micro-level risk, not platform-level strategy.

3. Organizing content around assets instead of ideas

When portfolio grids dominate the homepage, the platform feels secondary. LPs want to understand the thesis, not the past transactions.

4. Copy tone that reads like a project flyer

Language about “bringing properties to life,” “reimagining spaces,” or “transforming communities” is developer language. Investment-oriented LPs clock this immediately.

5. Visual hierarchy that puts the building above the firm

Developer brands elevate the building. Investor brands elevate the strategy, the market interpretation, and the team.

What Institutional Investors Expect Instead

Real estate LPs want to understand the lens through which the manager views the world. That lens should be visible immediately, and it should not rely on photography to carry the message.

Institutional cues come from:

- a confident but restrained color palette

- strong typography

- a clean, minimal layout

- a strategy-led homepage hero

- copy that signals clarity of thinking

- visuals that feel like a brand, not a flyer

These are the attributes LPs associate with managers they’ve backed before — not because of aesthetics alone, but because institutional brands correlate with platform maturity.

When Property Photography Actually Works

There are property types where photography can elevate rather than degrade:

- large-format industrial (scale communicates value)

- select urban office towers with architectural distinction

- hospitality, when design is part of the value story

- self-storage or niche industrial with drone imagery that conveys footprint

But even then, photography should be supporting, not leading. If the visual identity collapses without photos, the brand is fragile.

How to Fix Developer Mis-Signals

Managers can avoid developer cues by making targeted brand and design decisions.

1. Lead with strategy, not assets

The homepage should articulate the thesis. Photography can show up later, once the LP has context.

2. Use abstraction as your visual anchor

Color, geometry, and minimalistic art direction signal investment discipline more effectively than literal property imagery.

3. Create a tagline that expresses the platform, not the portfolio

A good line synthesizes property type, geography, and value creation method into a message LPs can immediately grasp.

4. Reframe asset visuals as evidence, not identity

Use properties to illustrate the strategy, not to define it. Put them in supporting slides, not the opening hero.

5. Build a visual system that stands even if you removed all photography

This is how real estate brands become memorable and truly institutional.

The Brand Question Every Real Estate Manager Should Ask

If you removed every image of every building from your materials, would a prospective LP still know who you are?

If the answer is no, the brand is not yet institutional. It is still anchored in the project-level identity of a developer.

LPs need to see maturity, intentionality, and clarity at the platform level. They need to understand the firm, not just the assets.

And above all else, they need to feel that the manager understands how to tell an investment story — not a construction story.

In a category where visual signals do much of the early sorting, getting this distinction right is not cosmetic. It is strategic. And it is often the difference between being perceived as a manager with a coherent thesis and being mistaken for something else entirely.

Your Website Creates the First Impression — Not Your Pitchbook

Real estate managers often assume the pitchbook is the primary place where LPs begin evaluating the story. In reality, the first exposure is nearly always digital. Before a call is scheduled or a deck is opened, LPs will search the firm, scan the homepage, and form an early impression based almost entirely on the website.

And because websites change far less frequently than pitchbooks — usually every four to six years — this digital first impression holds enormous weight. The website becomes the visual anchor of the entire brand. It’s where LPs get their bearings. It’s where they decide whether the firm looks organized, mature, and credible. And those judgments happen fast.

Within five seconds, LPs have already concluded whether the manager is worth learning more about. That is not because they are superficial. It is because they have learned to read early signals that correlate strongly with institutional readiness.

What LPs Look For Instantly

Real estate LPs do not begin by reading your content. In the first few seconds, they are scanning for category and coherence.

1. Does this firm look like an investor — or a developer?

This is the single biggest digital risk in the category.

Real estate managers unintentionally signal “developer” more often than they realize. They lead with full-bleed photos of individual buildings, interior shots, or project-specific imagery that feels like an offering memorandum.

Developer visuals signal:

- entitlement risk

- construction risk

- timing volatility

- project-specific uncertainty

If the LP is not explicitly looking for that exposure, they move on mentally before they’ve read a word.

Institutional real estate managers should lead with strategy, not assets. Photography should support the brand, not define it.

2. Does the digital brand stand on its own without property photos?

If removing the property imagery leaves you with nothing memorable, you don’t yet have a brand — you have a template.

LPs respond to websites that communicate identity through:

- color

- typography

- composition

- abstraction

- tone

These elements are what make the site feel sophisticated. Property photos can enhance the brand, but they cannot carry it.

3. How modern and organized does the site feel?

LPs interpret digital order as operational order.

When a site looks dated or overloaded — long walls of text, cluttered pages, outdated layouts — LPs subconsciously extend those impressions to the rest of the organization.

Conversely, clean hierarchy, disciplined white space, and thoughtful structure all signal that the firm is prepared for institutional scrutiny.

4. What does the tagline tell me?

The homepage headline is one of the highest-traffic brand assets the firm will ever create. LPs use it to determine:

- what the firm actually does

- whether the strategy is clear

- how the team sees its own value

- whether the thesis is generic or distinct

A strong tagline synthesizes property type, geography, value creation, and culture in a single line. A weak one creates instant sameness.

5. Do the visuals match the cycle?

Even without reading the content, LPs look for cues that the manager understands where the asset class sits in the cycle.

For example:

- industrial can get away with scale-centric photography

- office needs a thesis-driven opening narrative

- retail requires clarity around valuation and repositioning

- multifamily needs restraint to avoid signaling over-exuberance

LPs read these cues before they ever get to the words.

Why the Bar Is Surprisingly Low in Real Estate

Unlike private equity, where web and brand sophistication is relatively standardized, real estate digital presence varies dramatically. Many firms still operate with sites that were built five to ten years ago. The layouts feel outdated. The typography feels generic. The content feels thin.

LPs notice all of this. But more importantly, they notice when a firm looks different. In a category where sameness is the default, even modest improvements in digital design create disproportionate impact.

This is why a modern website is one of the most powerful levers a real estate firm has to shape early perception. You do not need a revolutionary brand to stand out. You simply need a clear, uncluttered, well-structured site that reflects the way LPs naturally scan.

The Photography Question — Use It Only If It Helps You

Real estate assets are physical, so managers often assume photography must be central. Sometimes that’s true. Industrial, in particular, benefits from aerial photography because scale is part of the story.

But in most other property types, photography is a high-risk, high-reward tool. Poor-quality photos — or even average ones — degrade the entire brand. And some property types simply don’t photograph well, especially Class B and C multifamily or aging retail centers.

Managers must be honest about whether photography strengthens or weakens their brand. If the assets are ordinary, they should not carry the aesthetic weight of the site.

Great managers invest early in real asset photography. They make it part of annual operations. They treat documentation as brand infrastructure. The firms who treat photography as a strategic asset always stand out.

Why the First Five Seconds Matter More Than the Rest of the Website

LPs rarely read deep into a site during early evaluation. What they are reacting to is coherence — not detail.

If the site feels disciplined, modern, and strategically composed, LPs assume the same about the platform. If it feels dated, generic, or developer-like, they assume the opposite.

These assumptions are not trivial. They influence:

- how LPs interpret the pitchbook

- whether they trust the team’s preparation

- how rigorous they expect the underwriting to be

- how they map the firm relative to peers

- whether the manager feels “ready” for institutional capital

The first five seconds of the website shape the frame through which everything else is understood.

The Goal Is Not Perfection — It’s Coherence

Real estate managers do not need cinematic websites or avant-garde design. LPs are not grading creativity. They are reading for order, maturity, and clarity.

A successful real estate website signals:

- “We know who we are.”

- “We know what investors care about.”

- “We understand where our strategy sits in the cycle.”

- “We are prepared.”

Those signals matter more than anything else a website can communicate.

In a category where strategies often overlap and portfolios often look similar, the firms who control the first five seconds control the narrative. And in real estate, controlling the narrative early is often the difference between being considered and being forgotten.

Most Real Estate Brands Miss the Point

In real estate, “institutional” is a word that gets thrown around casually. Firms describe themselves as institutional because they have a certain AUM threshold, or because they serve pension funds, or because they’ve moved beyond friends-and-family capital. But those criteria, on their own, do not create the perception of institutional quality. LPs define “institutional” through a different lens. They are reading for signals — subtle ones — that suggest maturity, preparedness, and credibility.

A real estate manager can have a billion dollars of assets and still look non-institutional. Another manager can be on Fund I and look far more polished. Institutional branding is not about size. It is about coherence, confidence, and the way the firm expresses its strategy and culture through design, language, and structure.

Real estate managers often underestimate how quickly LPs pick up on these signals. They assume investors will “see past” a dated website or a generic deck. But LPs do not interpret these artifacts as surface-level issues. They interpret them as indicators of how the rest of the platform operates.

Institutional branding is therefore not a layer added at the end. It is one of the clearest proxies an LP has for whether the manager is ready for institutional capital in the first place.

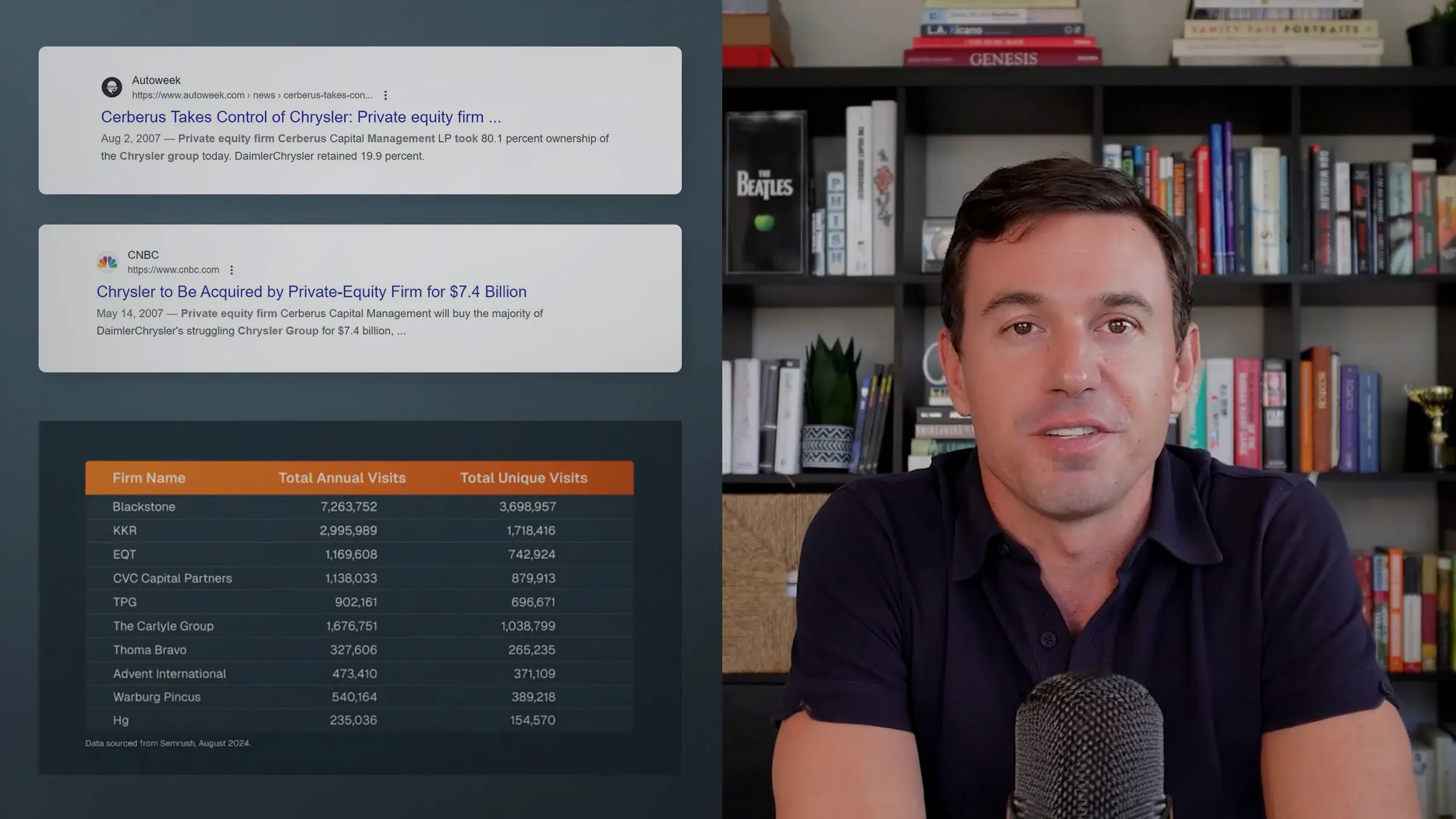

Why Real Estate Branding Lags Behind Private Equity

Real estate managers typically come from the operator side of the industry. They were developers, construction managers, acquisitions professionals, or brokers before launching a fund. Their instincts are rooted in execution, not presentation. And many have built successful track records without ever needing to communicate with LPs in an institutional format.

That background is not a flaw. It’s part of why the industry works. But it also creates a persistent gap between how managers think about their platform and how LPs expect to consume information. In private equity, the presentation of the firm has been part of the discipline for decades. In real estate, that discipline only emerges when a manager begins raising institutional capital for the first time.

This creates a wide spectrum of brand maturity across the industry. Some firms lean heavily into developer-style aesthetics, using photography and layout patterns that signal project-level risk. Others mirror private equity so closely that they lose the distinctive qualities of a real estate investor. The institutional middle is where the strongest brands live.

The Aesthetic Difference Between Developers and Investors

Most of the pitfalls in real estate branding come back to a single issue: many firms unintentionally present themselves as developers instead of investors. LPs react strongly to this distinction. Developer cues signal a different category of risk — entitlements, construction, timing, and project-level uncertainty. Investors, on the other hand, manage portfolios, not projects. Their role is to assess, acquire, operate, and harvest assets in a way that fits a defined strategy.

When a real estate manager’s website or pitchbook looks like a sales brochure for a single building, LPs immediately begin to question whether the platform is ready for institutional capital. They want abstraction, not literalism. They want a brand that can communicate ideas and strategy, not simply showcase square footage.

This is why trophy-asset photography can work at scale — and why almost everything else doesn’t. If the assets do not photograph well, or if the photography is inconsistent, it diminishes the entire brand. The default direction should be to build a visual identity that stands on its own even when the property photos are removed.

What Great Institutional Real Estate Brands Have in Common

Across the real estate firms that truly get this right, the same characteristics show up repeatedly:

1. A Visual System That Stands Alone

Color, typography, motion, and composition combine to create a recognizable identity. The brand is not carried by the properties; the properties are carried by the brand.

2. A Clear, Memorable Positioning Line

The homepage tagline encapsulates the thesis, the value creation method, and the tone of the organization. It is concise, distinct, and written in a way that a CIO could repeat effortlessly.

3. A Modern, Minimalist Digital Experience

Clean UX/UI, clear hierarchy, fast-loading pages, and restrained use of photography all create the impression of order. LPs interpret cleanliness as competence. Clutter creates uncertainty.

4. A Consistent, Mature Design Language Across All Materials

The pitchbook, website, tear sheets, and PPM should feel like components of the same system. This consistency signals that the firm is operationally organized — an attribute LPs care about deeply.

5. A Willingness to Avoid Generic Templates

The biggest differentiator between institutional and non-institutional brands is a willingness to abandon the clichés of the category. Cookie-cutter apartment photos, overused color palettes, and standard industry copy all contribute to the sense of sameness.

Hines: A Case Study in Institutional Real Estate Branding

Hines is one of the few real estate firms that has built a brand as recognizable as many private equity managers. Their use of a deep crimson red is bold, especially in a category where red is often avoided due to its financial associations. But it works because the entire identity is coherent. It feels global. It feels confident. And it aligns seamlessly with the scale and sophistication of the platform.

Equally important, Hines has invested heavily in content. Their insights, research, and thought leadership reinforce the brand in a way that many managers overlook. Content is not decoration. It is part of the credibility engine. And for LPs, a steady cadence of high-quality thinking signals maturity.

What Institutional Branding Is Really Signaling

At the end of the day, institutional branding is not about color palettes or fonts. It is about reducing friction in the diligence process. A well-executed brand does three things:

- It communicates that the manager understands LP expectations.

- It demonstrates organizational maturity.

- It reframes the strategy in a way that helps LPs understand the opportunity quickly.

LPs want confidence. They want clarity. And they want to feel that the manager they are considering is playing at a level appropriate for institutional capital.

The external brand is the proxy for all of that.

Institutional Is a Feeling, Not a Formula

The best institutional brands in real estate communicate something deeper than graphic design. They express conviction, coherence, and preparedness. They tell LPs that the manager has architected its platform thoughtfully. They make the story easier to understand and the opportunity easier to trust.

Institutional is not a checklist. It is a feeling LPs get when a manager has taken the time to articulate who they are and why their strategy matters. In real estate — an industry built on physical assets but driven by perception — that feeling is often the difference between being evaluated and being overlooked.

Most Real Estate Stories Start in the Wrong Place

Real estate managers often begin their pitchbooks and websites with a long description of the firm. They lead with the number of employees, total AUM, years in business, or a generic explanation of their strategy. This is understandable. Most real estate firms are operator-led, and operators instinctively talk about what they’ve built, what they own, or how they manage their properties.

But LPs aren’t looking for a chronology. They’re looking for a point of view. And the order in which you tell your story has a direct impact on how LPs understand the opportunity. A poorly structured narrative forces them to hunt for meaning. A well-structured one gives them a clear, immediate sense of whether the strategy deserves attention.

Real estate is highly cyclical and extremely sensitivity-driven. LPs evaluate managers through the lens of “why this strategy now,” often before they evaluate “why this team.” If you lead with the wrong section, you’re already fighting uphill.

The First Question LPs Want Answered

When LPs open a deck or a website, the question running through their mind is simple:

“Where are we in the cycle — and how does this strategy take advantage of it?”

Real estate does not behave like private equity, where GPs can sometimes transcend sector cycles with a strong operating framework or differentiated sourcing model. In real estate, the asset type and market context are part of the story. If the environment is against you, LPs want to understand whether you have a thesis that addresses it.

In other words, LPs evaluate the market first and the manager second.

The narrative must reflect that order.

Why Most Real Estate Firms Over-Explain the Basics

Another common misstep is spending too much time defining the property type or explaining obvious mechanics. LPs do not need a lecture on what workforce housing is, or how industrial cash flows work, or the difference between Class A and Class B assets. They already know all of this.

What they want is the manager’s interpretation of the opportunity:

- What has changed in this market?

- What do you see that others don’t?

- Why does this geography matter right now?

- Why is this asset type compressed or mispriced?

- What structural forces are supporting or undermining this strategy?

A real estate investment story is not an encyclopedic overview. It is a curated argument.

The Right Structure for a Real Estate Investment Story

To give LPs what they want — quickly — real estate managers should structure their narrative around three sections.

1. The Market Thesis (Where the Opportunity Lives)

This is where most real estate stories need to start, because this is where LPs’ heads already are.

The market thesis should establish:

- the cycle position

- valuation dynamics

- supply-demand imbalances

- geographic specifics

- structural drivers (demographics, migration, policy, infrastructure)

This should be crisp, not sprawling. LPs don’t want twenty pages of macro research in a deck. But they do want a clear summary of why now is an attractive moment to deploy capital behind your strategy.

The best market theses are contrarian without being reckless, or consensus-aligned without sounding generic.

2. The Strategy Mechanics (How the Opportunity Is Captured)

Once LPs understand the opportunity, they want to understand how you take advantage of it.

This is where most managers revert to generic phrasing. Instead, this section should unpack the specific mechanics your team uses to create value:

- sourcing edge

- underwriting nuance

- operational philosophy

- technology enablement

- renovation or repositioning framework

- leasing and retention strategy

- defensive measures

This is where smaller and midsized managers often shine. They may not have the brand recognition of a large platform, but they often have richer detail and more direct experience. When expressed clearly, that detail becomes a differentiator.

3. The Team Edge (Why You Are the Right Jockey for This Horse)

Only after LPs understand the asset class and the strategy do they want to understand the people.

This section should emphasize:

- firm history

- team pedigree

- track record

- culture and alignment

- repeatable processes

- organizational maturity

This is also where the brand plays a subtle but important role. If the team slide looks dated, cluttered, or visually inconsistent, LPs read that as a proxy for operational maturity. A well-designed team section reinforces the sense that the firm is organized, thoughtful, and prepared for institutional scrutiny.

Why Visual Structure Matters as Much as Narrative Structure

Real estate stories are not just read; they are scanned.

LPs evaluate:

- the opening headline

- the first few slides

- the homepage hero

- the imagery

- the composition

- the tone

If your story is structured well but expressed through outdated visuals, LPs may never get to the substance. This is why the website, pitchbook design, and brand elements matter. They create the frame through which the entire story is interpreted.

The reverse is also true. A visually coherent and modern system makes even a complex or contrarian strategy feel more understandable and credible.

Avoiding Developer Vibes — And Why It Matters

Many real estate managers unintentionally create a narrative structure that resembles a development brochure. They lead with property photos, discuss individual assets too early, or present themselves as operators rather than investment managers.

LPs read this as a risk signal. They assume you are taking construction, entitlement, or project-level volatility unless you make a clear case otherwise.

The investment story should lead with strategy, not assets. Assets illustrate the story later; they should not define it.

The Goal of the Narrative: Coherence, Not Magnitude

LPs do not need to be overwhelmed. They do not need exhaustive data. What they want is coherence:

- a clear thesis

- a strategy that matches the thesis

- a team whose skills match the strategy

The story works when these pieces fit together without friction. When the market thesis, strategy mechanics, and team edge reinforce one another, LPs feel the logic internally. And when that happens, the manager doesn’t sound like everyone else — even if the strategy is similar to dozens of competitors.

A real estate investment story succeeds when it feels like it could not belong to anyone else.