.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Your Website Creates the First Impression — Not Your Pitchbook

Real estate managers often assume the pitchbook is the primary place where LPs begin evaluating the story. In reality, the first exposure is nearly always digital. Before a call is scheduled or a deck is opened, LPs will search the firm, scan the homepage, and form an early impression based almost entirely on the website.

And because websites change far less frequently than pitchbooks — usually every four to six years — this digital first impression holds enormous weight. The website becomes the visual anchor of the entire brand. It’s where LPs get their bearings. It’s where they decide whether the firm looks organized, mature, and credible. And those judgments happen fast.

Within five seconds, LPs have already concluded whether the manager is worth learning more about. That is not because they are superficial. It is because they have learned to read early signals that correlate strongly with institutional readiness.

What LPs Look For Instantly

Real estate LPs do not begin by reading your content. In the first few seconds, they are scanning for category and coherence.

1. Does this firm look like an investor — or a developer?

This is the single biggest digital risk in the category.

Real estate managers unintentionally signal “developer” more often than they realize. They lead with full-bleed photos of individual buildings, interior shots, or project-specific imagery that feels like an offering memorandum.

Developer visuals signal:

- entitlement risk

- construction risk

- timing volatility

- project-specific uncertainty

If the LP is not explicitly looking for that exposure, they move on mentally before they’ve read a word.

Institutional real estate managers should lead with strategy, not assets. Photography should support the brand, not define it.

2. Does the digital brand stand on its own without property photos?

If removing the property imagery leaves you with nothing memorable, you don’t yet have a brand — you have a template.

LPs respond to websites that communicate identity through:

- color

- typography

- composition

- abstraction

- tone

These elements are what make the site feel sophisticated. Property photos can enhance the brand, but they cannot carry it.

3. How modern and organized does the site feel?

LPs interpret digital order as operational order.

When a site looks dated or overloaded — long walls of text, cluttered pages, outdated layouts — LPs subconsciously extend those impressions to the rest of the organization.

Conversely, clean hierarchy, disciplined white space, and thoughtful structure all signal that the firm is prepared for institutional scrutiny.

4. What does the tagline tell me?

The homepage headline is one of the highest-traffic brand assets the firm will ever create. LPs use it to determine:

- what the firm actually does

- whether the strategy is clear

- how the team sees its own value

- whether the thesis is generic or distinct

A strong tagline synthesizes property type, geography, value creation, and culture in a single line. A weak one creates instant sameness.

5. Do the visuals match the cycle?

Even without reading the content, LPs look for cues that the manager understands where the asset class sits in the cycle.

For example:

- industrial can get away with scale-centric photography

- office needs a thesis-driven opening narrative

- retail requires clarity around valuation and repositioning

- multifamily needs restraint to avoid signaling over-exuberance

LPs read these cues before they ever get to the words.

Why the Bar Is Surprisingly Low in Real Estate

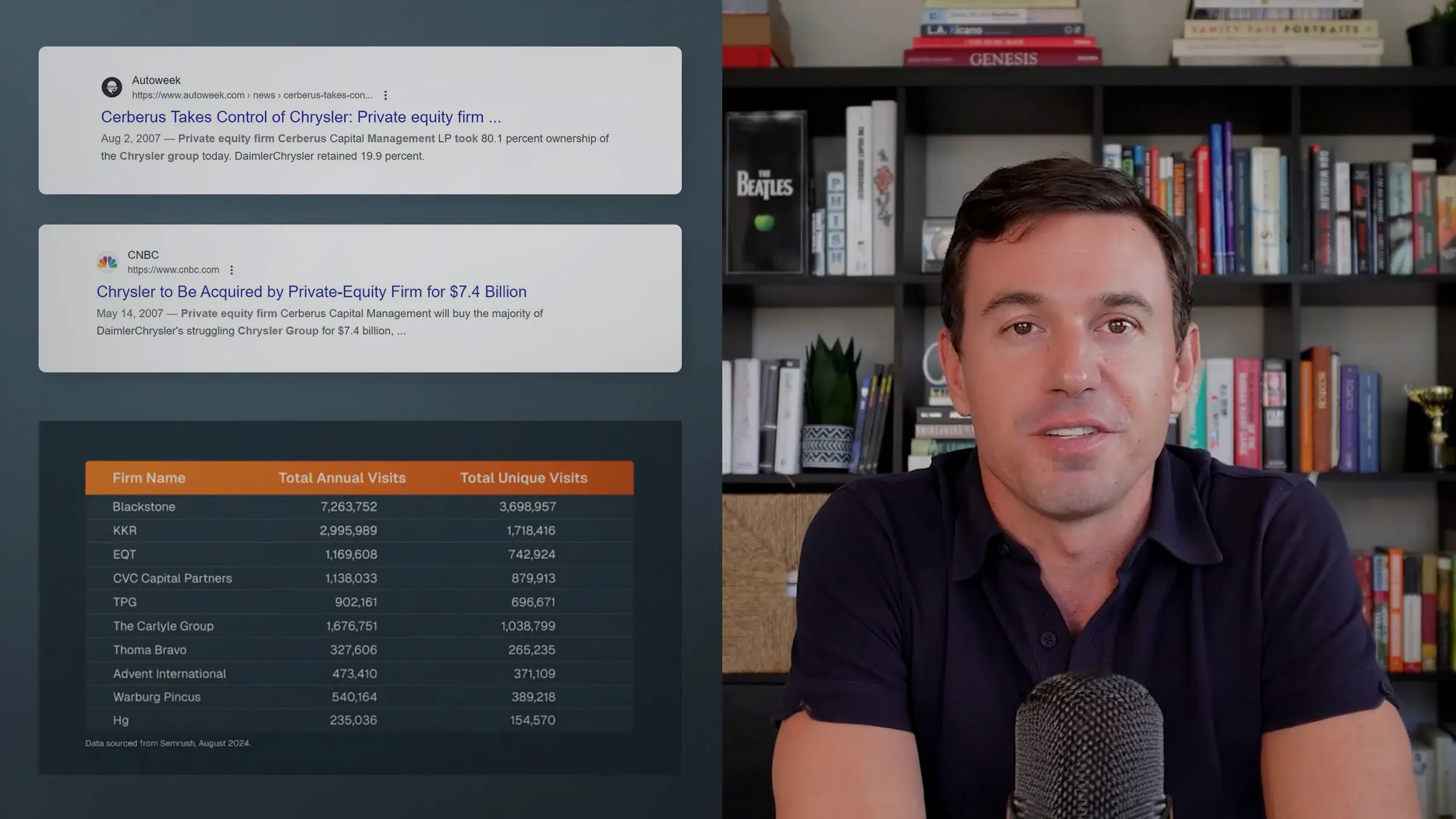

Unlike private equity, where web and brand sophistication is relatively standardized, real estate digital presence varies dramatically. Many firms still operate with sites that were built five to ten years ago. The layouts feel outdated. The typography feels generic. The content feels thin.

LPs notice all of this. But more importantly, they notice when a firm looks different. In a category where sameness is the default, even modest improvements in digital design create disproportionate impact.

This is why a modern website is one of the most powerful levers a real estate firm has to shape early perception. You do not need a revolutionary brand to stand out. You simply need a clear, uncluttered, well-structured site that reflects the way LPs naturally scan.

The Photography Question — Use It Only If It Helps You

Real estate assets are physical, so managers often assume photography must be central. Sometimes that’s true. Industrial, in particular, benefits from aerial photography because scale is part of the story.

But in most other property types, photography is a high-risk, high-reward tool. Poor-quality photos — or even average ones — degrade the entire brand. And some property types simply don’t photograph well, especially Class B and C multifamily or aging retail centers.

Managers must be honest about whether photography strengthens or weakens their brand. If the assets are ordinary, they should not carry the aesthetic weight of the site.

Great managers invest early in real asset photography. They make it part of annual operations. They treat documentation as brand infrastructure. The firms who treat photography as a strategic asset always stand out.

Why the First Five Seconds Matter More Than the Rest of the Website

LPs rarely read deep into a site during early evaluation. What they are reacting to is coherence — not detail.

If the site feels disciplined, modern, and strategically composed, LPs assume the same about the platform. If it feels dated, generic, or developer-like, they assume the opposite.

These assumptions are not trivial. They influence:

- how LPs interpret the pitchbook

- whether they trust the team’s preparation

- how rigorous they expect the underwriting to be

- how they map the firm relative to peers

- whether the manager feels “ready” for institutional capital

The first five seconds of the website shape the frame through which everything else is understood.

The Goal Is Not Perfection — It’s Coherence

Real estate managers do not need cinematic websites or avant-garde design. LPs are not grading creativity. They are reading for order, maturity, and clarity.

A successful real estate website signals:

- “We know who we are.”

- “We know what investors care about.”

- “We understand where our strategy sits in the cycle.”

- “We are prepared.”

Those signals matter more than anything else a website can communicate.

In a category where strategies often overlap and portfolios often look similar, the firms who control the first five seconds control the narrative. And in real estate, controlling the narrative early is often the difference between being considered and being forgotten.

Most Real Estate Brands Miss the Point

In real estate, “institutional” is a word that gets thrown around casually. Firms describe themselves as institutional because they have a certain AUM threshold, or because they serve pension funds, or because they’ve moved beyond friends-and-family capital. But those criteria, on their own, do not create the perception of institutional quality. LPs define “institutional” through a different lens. They are reading for signals — subtle ones — that suggest maturity, preparedness, and credibility.

A real estate manager can have a billion dollars of assets and still look non-institutional. Another manager can be on Fund I and look far more polished. Institutional branding is not about size. It is about coherence, confidence, and the way the firm expresses its strategy and culture through design, language, and structure.

Real estate managers often underestimate how quickly LPs pick up on these signals. They assume investors will “see past” a dated website or a generic deck. But LPs do not interpret these artifacts as surface-level issues. They interpret them as indicators of how the rest of the platform operates.

Institutional branding is therefore not a layer added at the end. It is one of the clearest proxies an LP has for whether the manager is ready for institutional capital in the first place.

Why Real Estate Branding Lags Behind Private Equity

Real estate managers typically come from the operator side of the industry. They were developers, construction managers, acquisitions professionals, or brokers before launching a fund. Their instincts are rooted in execution, not presentation. And many have built successful track records without ever needing to communicate with LPs in an institutional format.

That background is not a flaw. It’s part of why the industry works. But it also creates a persistent gap between how managers think about their platform and how LPs expect to consume information. In private equity, the presentation of the firm has been part of the discipline for decades. In real estate, that discipline only emerges when a manager begins raising institutional capital for the first time.

This creates a wide spectrum of brand maturity across the industry. Some firms lean heavily into developer-style aesthetics, using photography and layout patterns that signal project-level risk. Others mirror private equity so closely that they lose the distinctive qualities of a real estate investor. The institutional middle is where the strongest brands live.

The Aesthetic Difference Between Developers and Investors

Most of the pitfalls in real estate branding come back to a single issue: many firms unintentionally present themselves as developers instead of investors. LPs react strongly to this distinction. Developer cues signal a different category of risk — entitlements, construction, timing, and project-level uncertainty. Investors, on the other hand, manage portfolios, not projects. Their role is to assess, acquire, operate, and harvest assets in a way that fits a defined strategy.

When a real estate manager’s website or pitchbook looks like a sales brochure for a single building, LPs immediately begin to question whether the platform is ready for institutional capital. They want abstraction, not literalism. They want a brand that can communicate ideas and strategy, not simply showcase square footage.

This is why trophy-asset photography can work at scale — and why almost everything else doesn’t. If the assets do not photograph well, or if the photography is inconsistent, it diminishes the entire brand. The default direction should be to build a visual identity that stands on its own even when the property photos are removed.

What Great Institutional Real Estate Brands Have in Common

Across the real estate firms that truly get this right, the same characteristics show up repeatedly:

1. A Visual System That Stands Alone

Color, typography, motion, and composition combine to create a recognizable identity. The brand is not carried by the properties; the properties are carried by the brand.

2. A Clear, Memorable Positioning Line

The homepage tagline encapsulates the thesis, the value creation method, and the tone of the organization. It is concise, distinct, and written in a way that a CIO could repeat effortlessly.

3. A Modern, Minimalist Digital Experience

Clean UX/UI, clear hierarchy, fast-loading pages, and restrained use of photography all create the impression of order. LPs interpret cleanliness as competence. Clutter creates uncertainty.

4. A Consistent, Mature Design Language Across All Materials

The pitchbook, website, tear sheets, and PPM should feel like components of the same system. This consistency signals that the firm is operationally organized — an attribute LPs care about deeply.

5. A Willingness to Avoid Generic Templates

The biggest differentiator between institutional and non-institutional brands is a willingness to abandon the clichés of the category. Cookie-cutter apartment photos, overused color palettes, and standard industry copy all contribute to the sense of sameness.

Hines: A Case Study in Institutional Real Estate Branding

Hines is one of the few real estate firms that has built a brand as recognizable as many private equity managers. Their use of a deep crimson red is bold, especially in a category where red is often avoided due to its financial associations. But it works because the entire identity is coherent. It feels global. It feels confident. And it aligns seamlessly with the scale and sophistication of the platform.

Equally important, Hines has invested heavily in content. Their insights, research, and thought leadership reinforce the brand in a way that many managers overlook. Content is not decoration. It is part of the credibility engine. And for LPs, a steady cadence of high-quality thinking signals maturity.

What Institutional Branding Is Really Signaling

At the end of the day, institutional branding is not about color palettes or fonts. It is about reducing friction in the diligence process. A well-executed brand does three things:

- It communicates that the manager understands LP expectations.

- It demonstrates organizational maturity.

- It reframes the strategy in a way that helps LPs understand the opportunity quickly.

LPs want confidence. They want clarity. And they want to feel that the manager they are considering is playing at a level appropriate for institutional capital.

The external brand is the proxy for all of that.

Institutional Is a Feeling, Not a Formula

The best institutional brands in real estate communicate something deeper than graphic design. They express conviction, coherence, and preparedness. They tell LPs that the manager has architected its platform thoughtfully. They make the story easier to understand and the opportunity easier to trust.

Institutional is not a checklist. It is a feeling LPs get when a manager has taken the time to articulate who they are and why their strategy matters. In real estate — an industry built on physical assets but driven by perception — that feeling is often the difference between being evaluated and being overlooked.

Most Real Estate Stories Start in the Wrong Place

Real estate managers often begin their pitchbooks and websites with a long description of the firm. They lead with the number of employees, total AUM, years in business, or a generic explanation of their strategy. This is understandable. Most real estate firms are operator-led, and operators instinctively talk about what they’ve built, what they own, or how they manage their properties.

But LPs aren’t looking for a chronology. They’re looking for a point of view. And the order in which you tell your story has a direct impact on how LPs understand the opportunity. A poorly structured narrative forces them to hunt for meaning. A well-structured one gives them a clear, immediate sense of whether the strategy deserves attention.

Real estate is highly cyclical and extremely sensitivity-driven. LPs evaluate managers through the lens of “why this strategy now,” often before they evaluate “why this team.” If you lead with the wrong section, you’re already fighting uphill.

The First Question LPs Want Answered

When LPs open a deck or a website, the question running through their mind is simple:

“Where are we in the cycle — and how does this strategy take advantage of it?”

Real estate does not behave like private equity, where GPs can sometimes transcend sector cycles with a strong operating framework or differentiated sourcing model. In real estate, the asset type and market context are part of the story. If the environment is against you, LPs want to understand whether you have a thesis that addresses it.

In other words, LPs evaluate the market first and the manager second.

The narrative must reflect that order.

Why Most Real Estate Firms Over-Explain the Basics

Another common misstep is spending too much time defining the property type or explaining obvious mechanics. LPs do not need a lecture on what workforce housing is, or how industrial cash flows work, or the difference between Class A and Class B assets. They already know all of this.

What they want is the manager’s interpretation of the opportunity:

- What has changed in this market?

- What do you see that others don’t?

- Why does this geography matter right now?

- Why is this asset type compressed or mispriced?

- What structural forces are supporting or undermining this strategy?

A real estate investment story is not an encyclopedic overview. It is a curated argument.

The Right Structure for a Real Estate Investment Story

To give LPs what they want — quickly — real estate managers should structure their narrative around three sections.

1. The Market Thesis (Where the Opportunity Lives)

This is where most real estate stories need to start, because this is where LPs’ heads already are.

The market thesis should establish:

- the cycle position

- valuation dynamics

- supply-demand imbalances

- geographic specifics

- structural drivers (demographics, migration, policy, infrastructure)

This should be crisp, not sprawling. LPs don’t want twenty pages of macro research in a deck. But they do want a clear summary of why now is an attractive moment to deploy capital behind your strategy.

The best market theses are contrarian without being reckless, or consensus-aligned without sounding generic.

2. The Strategy Mechanics (How the Opportunity Is Captured)

Once LPs understand the opportunity, they want to understand how you take advantage of it.

This is where most managers revert to generic phrasing. Instead, this section should unpack the specific mechanics your team uses to create value:

- sourcing edge

- underwriting nuance

- operational philosophy

- technology enablement

- renovation or repositioning framework

- leasing and retention strategy

- defensive measures

This is where smaller and midsized managers often shine. They may not have the brand recognition of a large platform, but they often have richer detail and more direct experience. When expressed clearly, that detail becomes a differentiator.

3. The Team Edge (Why You Are the Right Jockey for This Horse)

Only after LPs understand the asset class and the strategy do they want to understand the people.

This section should emphasize:

- firm history

- team pedigree

- track record

- culture and alignment

- repeatable processes

- organizational maturity

This is also where the brand plays a subtle but important role. If the team slide looks dated, cluttered, or visually inconsistent, LPs read that as a proxy for operational maturity. A well-designed team section reinforces the sense that the firm is organized, thoughtful, and prepared for institutional scrutiny.

Why Visual Structure Matters as Much as Narrative Structure

Real estate stories are not just read; they are scanned.

LPs evaluate:

- the opening headline

- the first few slides

- the homepage hero

- the imagery

- the composition

- the tone

If your story is structured well but expressed through outdated visuals, LPs may never get to the substance. This is why the website, pitchbook design, and brand elements matter. They create the frame through which the entire story is interpreted.

The reverse is also true. A visually coherent and modern system makes even a complex or contrarian strategy feel more understandable and credible.

Avoiding Developer Vibes — And Why It Matters

Many real estate managers unintentionally create a narrative structure that resembles a development brochure. They lead with property photos, discuss individual assets too early, or present themselves as operators rather than investment managers.

LPs read this as a risk signal. They assume you are taking construction, entitlement, or project-level volatility unless you make a clear case otherwise.

The investment story should lead with strategy, not assets. Assets illustrate the story later; they should not define it.

The Goal of the Narrative: Coherence, Not Magnitude

LPs do not need to be overwhelmed. They do not need exhaustive data. What they want is coherence:

- a clear thesis

- a strategy that matches the thesis

- a team whose skills match the strategy

The story works when these pieces fit together without friction. When the market thesis, strategy mechanics, and team edge reinforce one another, LPs feel the logic internally. And when that happens, the manager doesn’t sound like everyone else — even if the strategy is similar to dozens of competitors.

A real estate investment story succeeds when it feels like it could not belong to anyone else.

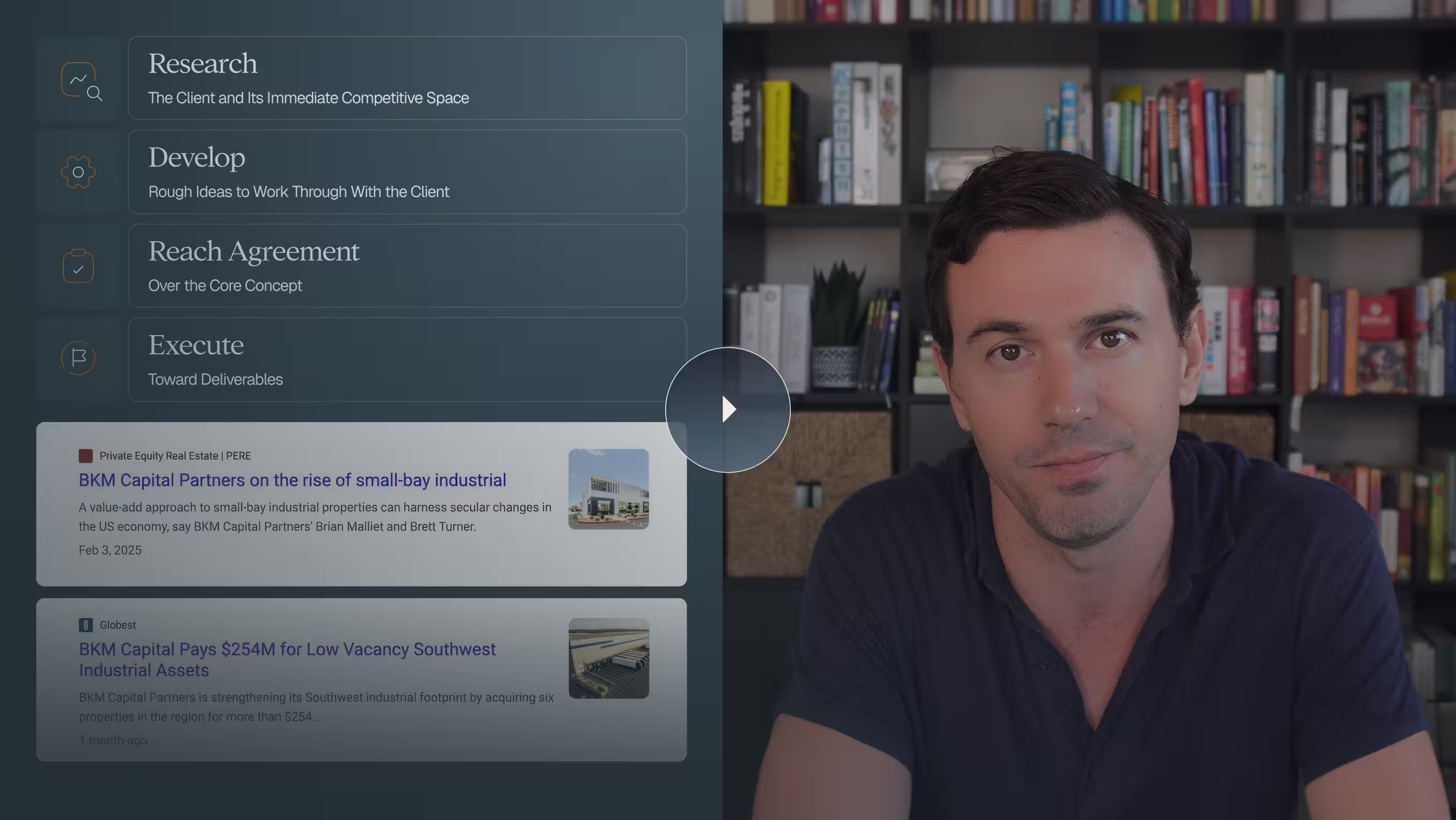

How site architecture, naming, and narrative structure influence clarity during a pivotal growth moment

As real estate managers expand from a single fund to a multi-product platform, their website becomes one of the first places where the transition either feels seamless or confusing. DG has seen this evolution across managers of varying sizes, and while the strategic path differs for each firm, the digital challenges they encounter tend to fall into familiar patterns.

The core issue is not the number of products; it’s the lack of a structural system that helps users understand how everything fits together. Without intentional design and narrative choices, the website can inadvertently mask the firm’s strengths or create friction before an investor or advisor has the chance to engage meaningfully.

Below are the four mistakes that appear most consistently, and the principles that help avoid them.

1. Menu Structures That Mirror Internal Organization Rather Than User Needs

When firms add new vehicles — separate share classes, co-invest sleeves, open-end programs, or wealth-channel offerings — the navigation often expands reactively. Internal teams know the differences intimately; visitors typically do not.

Common pitfalls include:

- Menus organized around internal team structures rather than strategy families

- Unclear distinctions between “funds,” “strategies,” and “products”

- Dropdowns that grow horizontally and vertically without hierarchy

- Product pages nested three or four levels deep

Users encountering this structure may not know where to start or may misinterpret product relationships.

What works instead

Effective multi-product menus typically:

- Group offerings by strategy intent (e.g., income, diversified, sector-focused), not by fund number

- Keep top-level navigation minimal and intuitive

- Use landing pages that orient the user before presenting product-specific detail

- Make wealth-channel and institutional pathways distinct when needed

2. Product Naming That Doesn’t Communicate Purpose

As firms grow, product naming often emerges organically: Fund I, Fund II, Capital Partners, Opportunity Fund, Development Fund, etc. While these names make sense internally, they may not clearly signal differences to external audiences.

Common naming issues include:

- Similar names for materially different strategies

- Numerical naming conventions that obscure purpose

- Acronyms that require inside knowledge

- Names that do not reflect product evolution across cycles or markets

The risk is not confusion for its own sake; it’s that unclear names can delay a user’s understanding of what the product does and who it is for.

What works instead

Strong multi-product naming conventions:

- Clarify the objective of each product (income, appreciation, sector exposure)

- Use consistent naming logic across all vehicles

- Avoid internal shorthand unless it serves a clear audience purpose

- Provide short descriptors or “micro-taglines” beneath each product name

Naming is not branding ornamentation; it is part of the comprehension system.

3. Audience Confusion When Institutional and Wealth-Channel Products Live Side by Side

As more managers expand into advisor-distributed or retail-accessible vehicles, the website must serve two or more distinct audiences, each with different expectations regarding depth, disclosure, and navigation.

Without intentional architecture, site visitors may encounter:

- Institutional materials appearing alongside advisor-oriented products

- Wealth-channel disclosures within institutional strategy explanations

- Unclear pathways to subscription mechanics or fact sheets

- Overlapping terminology across audience types

This can create uncertainty about which information applies to whom.

What works instead

Effective multi-audience sites often rely on:

- Distinct microsites for wealth-channel products

- Clear, visible entry points tailored to advisors vs. institutions

- Repeated visual cues that reinforce which audience a page is speaking to

- Disclosure frameworks aligned to each product type

This approach helps organize the user's experience on the website.

4. Homepage Narrative Clutter Caused by Growing Complexity

The homepage is often the last part of the website to be updated as firms add products. What begins as a clean narrative statement can accumulate:

- multiple strategies

- competing messages

- rotating banners

- dense performance or distribution information

- overlapping calls to action

The result is a homepage that feels crowded and unfocused, even when the underlying platform is strong.

What works instead

High-performing multi-product homepages usually share three characteristics:

A. A single, firm-level narrative anchor

This clarifies what the platform stands for, separate from any one vehicle.

B. Simple directional pathways

Examples: “Explore Our Strategies,” “For Advisors,” “For Institutions.”

C. A consistent visual system

New products fit into existing modules rather than requiring new homepage structures each time.

The homepage should introduce the platform clearly, then direct users to the right depth of information without overwhelming them.

Closing Thought

Evolving from a single product to a multi-product platform is a meaningful milestone for any real estate manager. The website can either reinforce that evolution or complicate it. With intentional architecture — clear menus, thoughtful naming, defined audience pathways, and a disciplined homepage narrative — managers create an environment where their capabilities are understood quickly and confidently.

A well-structured website does not just present the platform; it supports the strategy.

How development-forward and operations-heavy teams can reposition themselves as disciplined, investment-first platforms

Many real estate managers originate as operators — development groups, vertically integrated platforms, or teams built around deep local execution capability. This “operator DNA” is often a genuine competitive strength: it creates insight, informs underwriting, and establishes credibility in specific markets or asset types.

But when these teams begin raising outside capital, especially from institutional LPs or advisors, they often face a branding challenge: how to present themselves as investment managers without losing the advantages that make them compelling operators.

This transition is not about suppressing operator identity, rather translating operational expertise into a strategic, investment-led narrative that audiences can evaluate with clarity and confidence.

Across DG’s work with development-forward and operations-heavy real estate managers, three themes consistently shape successful repositioning.

1. Reframing Operational Expertise as an Investment Edge

Operator-led teams typically possess knowledge that is difficult for capital allocators to replicate: entitlement judgment, construction sequencing, supply-demand nuance, or lease-up dynamics. The challenge is that, left unframed, operational depth can feel like project-level detail rather than investment-level insight.

The strongest repositionings articulate operational capabilities in investment terms, such as:

- what the team sees earlier than peers,

- how operational discipline affects risk mitigation,

- how execution creates repeatable value, and

- why local expertise leads to better decision-making, not just better projects.

2. Structuring the Narrative to Feel Allocator-Led, Not Project-Led

When development or operations teams evolve into investment managers, the biggest hurdle is often narrative structure, not substance. Operator-led firms may default to storytelling through individual projects, which can unintentionally shift attention toward asset-level execution rather than strategy-level thinking.

An investment-forward narrative typically sequences information as:

- Market or thematic context

- Strategy rationale

- Risk considerations and mitigants

- Team and platform capabilities

- Portfolio examples (not the other way around)

This order helps audiences understand why the strategy exists before they are introduced to how it appears in specific assets.

Why this matters

Allocator audiences often evaluate coherence and repeatability. A project-first narrative can make the strategy feel anecdotal; a rationale-first narrative makes the strategy feel intentional.

3. Recalibrating Brand Signals to Convey Institutional Readiness

Branding is one of the most powerful tools in helping an operator-defined team present as a disciplined investment manager. Visual cues, language choices, and site architecture all play a role in shaping perception.

Key shifts that support this transition include:

A. Language that is structured and measured

Approaches that focus on underwriting discipline, thematic reasoning, and investment criteria help balance the operator story with strategic clarity.

B. Visual systems that emphasize calm, consistency, and process

Operational platforms sometimes rely heavily on imagery that conveys activity — construction shots, before-and-after transformations, or fieldwork. These can be meaningful elements but often benefit from selective use, paired with diagrams, maps, or thesis exhibits that convey structure.

C. Website organization that leads with strategy rather than assets

A development firm’s website may naturally center around past work. An investment manager’s website tends to lead with thesis, approach, and portfolio behavior, using examples to support rather than define the narrative.

4. Preserving Authenticity While Expanding Perception

A common concern among operator-led teams is that repositioning might dilute the identity that makes them distinctive. In practice, the opposite is true: when operational insight is expressed through a disciplined investment framework, audiences tend to understand it more clearly and value it more directly.

Authenticity is preserved by:

- explaining how operational expertise informs underwriting;

- showing disciplined processes rather than highlighting isolated successes;

- maintaining clarity about where the team excels, rather than over-expanding claims;

- using project examples selectively, with consistent formatting and context.

The goal is not to “sound institutional.” The goal is to help allocators see the strategic logic behind the operational competence.

5. When Operator DNA Becomes a Competitive Advantage

Repositioned effectively, operator DNA becomes an investment identity that is:

- grounded in real-world execution,

- informed by practical experience,

- differentiated from purely financial platforms, and

- credible in markets where nuance matters.

For many allocators, the most compelling managers are those who can combine strategic clarity with operational depth — a pairing that gives context to decisions and confidence to underwriting assumptions.

Operator-led teams often underestimate how powerful this combination is when communicated well. With the right structure, visual discipline, and narrative framing, the transition to an investment-manager identity becomes not just possible, but advantageous.

Closing Thought

Repositioning an operator-forward team as an investment manager doesn’t require reinventing the firm. It requires clarifying the bridge between how the team operates and how the strategy creates value for investors. When that translation is executed cleanly, through narrative, design, and brand structure, the operator story becomes one of the firm’s most compelling differentiators.

Most real estate managers think of their website as the primary digital expression of their firm. And in a structural sense, that’s true — the website is the permanent home for the brand, the place investors go to orient themselves, and the asset that sets the visual and narrative tone for everything else.

But a website is only the platform.

It is not the engine.

The firms that stand out are the ones that understand this distinction. The website establishes credibility; content sustains it. The website introduces you; content reinforces who you are. The website carries the brand; content proves the claims the brand is making.

Very few real estate managers take advantage of this. And because the category remains so quiet, anyone who invests even modestly in publishing high-quality content gains a disproportionate visibility advantage. In a world where institutional investors, advisors, family offices, and high-net-worth individuals all search for information online long before contacting a firm, silence is not neutral. It’s a lost opportunity.

Why the Website Must Stay Durable — and Why Content Must Move

A website has to be built for a long shelf life. It cannot bend itself around short-term market conditions, interest-rate environments, sector rotations, or fundraising cycles. Permanent pages need to communicate who the firm is and what it believes, not what the Fed or the cycle is dictating at the moment.

Content fills the gap between those two worlds. It’s the flexible layer — where the manager can interpret the market, show intellectual leadership, or demonstrate why its viewpoint is worth considering.

Put differently: The website is the foundation; the content is the motion.

This is especially important in real estate, where cycles can shift dramatically. When the market is dislocated, as it has been for several years, the firms that articulate a coherent point of view — on pricing, capital flows, submarket dynamics, or asset-class resilience — signal competence in a way that static website language simply cannot.

Most managers don’t do this.

Which is why those who do stand out.

Visibility Is a Competitive Advantage (Especially in Real Estate)

Real estate investment managers outside the mega-firm tier tend not to communicate publicly. They rely on relationships, fund cycles, and investor referrals. That model works — until it stops working.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world has changed.

Visibility is now a form of credibility.

Investors, advisors, and allocators search the same way everyone else does. They Google. They skim. They read a few sentences and decide whether to keep going. LLMs do the same thing, except at scale and with far less tolerance for missing information.

Most managers are invisible online.

Not because their strategies are bad — but because they have left nothing on the surface for anyone to find.

Firms that publish well-structured content — even three or four strong pieces a year — suddenly become discoverable. Their names begin appearing in natural-language queries. Their viewpoints get repeated. Their strategy becomes understandable to outsiders in a way most competitors never achieve.

Visibility compounds.

Silence does not.

Content as Proof: Showing What the Brand Promises

Most investment managers claim the same things:

- differentiated sourcing

- operational excellence

- cycle awareness

- deep regional expertise

- hands-on value creation

The problem is not that these claims are untrue. The problem is that almost no one provides proof.

This is where content fundamentally changes the game.

A strong content engine allows a manager to demonstrate:

- how it interprets its asset class

- what it believes about a specific geography

- how it thinks about capex or operations

- how it views risk, resilience, and volatility

- where it has created value in ways competitors couldn’t

Real examples deliver more credibility than any brand line ever will.

Proof points are rare in real estate marketing — which means they are disproportionately powerful when they appear.

A manager who says, “We are experts in X,” disappears into the noise.

A manager who shows it, repeatedly and coherently, becomes memorable.

LLMs Thrive on Content — and They Will Define Your Firm If You Don’t

You’ve said this many times, and it bears repeating in plain language:

If you don’t define your story, LLMs will define it for you.

In an LLM-driven world:

- Silence becomes misclassification.

- Incomplete narratives become inaccurate narratives.

- A lack of content becomes the presence of someone else’s content — about your category, your peers, or your strategy.

LLMs cannot infer your value proposition from a sparse website. They need depth, repetition, and context to understand what you do and who you serve. Without that, they collapse your identity into a generic category.

Publishing content isn’t just good marketing; it’s defensive architecture.

It protects your positioning in the next generation of discovery tools.

And because your competitors aren’t doing it, your advantage is larger than it looks.

What Real Estate Managers Should Actually Be Publishing

Managers don’t need to become media companies. They don’t need weekly posts. They need clarity and cadence. In most cases, the following categories create the most lift:

- cycle commentary that helps investors make sense of the market

- thematic insights on specific property types

- submarket perspectives reflecting real on-the-ground experience

- explanations of how the firm actually creates value

- short pieces that simplify the story for advisors and end-clients

- educational content that demystifies real estate for newcomers

- behind-the-scenes insight into the team’s philosophy or approach

Most firms already have these viewpoints internally.

They simply haven’t written them down.

How a Content Engine Strengthens Capital Formation Over Time

Content doesn’t raise a fund by itself. But it supports every other stage of capital formation:

- It increases the chance someone discovers you before you contact them.

- It gives investors something to skim before the first meeting.

- It provides advisors with material they can pass downstream.

- It reinforces the pitchbook rather than repeating it.

- It allows the manager to show the durability of its thinking over time.

- It narrows the gap between “unknown manager” and “credible contender.”

Because real estate is so tactile and so cyclical, the managers who narrate their corner of the market become easier for investors to trust. They sound practiced. They sound engaged. They sound like they know their lane.

Visibility becomes familiarity.

Familiarity becomes comfort.

Comfort becomes allocation.

The Real Point

Most real estate managers are not competing on content.

They are barely competing on communication at all.

A website gives you structure.

Content gives you momentum.

A website proves you’re organized.

Content proves you’re right.

A website establishes the brand.

Content makes the brand believable.

In an industry where almost everyone sounds identical, the firms that show their thinking — rather than merely stating it — are the ones that break away from the pack.

A content engine is not a luxury.

It is the missing piece of the modern real estate brand.