.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Most real estate managers don’t need a wildly inventive website. They need one that works. The difference between a credible institutional presence and a site that quietly undermines the story is rarely a matter of creativity — it’s consistency, clarity, and basic execution.

And because the bar is so low in this category, even a handful of smart decisions can move a firm from “small” to “institutional” in the eyes of investors, advisors, and transaction counterparts.

Below is a practical guide to the do’s and don’ts that matter most. These aren’t theoretical design opinions or aesthetic preferences. They’re the actual signals investors subconsciously read — the ones that either elevate the story or raise doubts before the first meeting even happens.

Do: Invest in Real Design Talent

Institutional websites don’t happen by accident. They come from designers who understand spacing, grid systems, rhythm, typography, and how to structure information so that it feels calm instead of chaotic. You don’t need a world-famous firm to do this. You simply need real design talent.

What matters is not whether the site uses a trendy typeface or a perfectly minimalist layout. What matters is whether it feels intentional and modern — not improvised by someone in the back office who “took a design class once.”

The lift from professional design is enormous. And in a category where many firms don’t invest in it, the advantage is even larger.

Do: Keep Structure Simple and Intuitive

Real estate websites become confusing when they try to explain everything at once. The firms that get this right take the opposite approach. They think like their investor:

Where do I expect this information to be?

Most credible sites follow a logical structure:

Homepage → About/Approach → Portfolio → Team → Insights (or News) → Contact

Managers can rename sections however they like, but the rhythm should remain intact. Visitors should never need to puzzle out where to go next. The navigation should feel quiet and predictable — the opposite of clever.

This is especially important when a firm has multiple funds or vehicles. The top nav should help visitors self-route rather than forcing them to decode which part of the site applies to them.

Do: Let Your Portfolio Prove Something

Investors always check the portfolio page. The question is whether the portfolio communicates anything beyond ownership.

A great portfolio section does not require dozens of assets or elaborate case studies. It simply needs to show depth in the way the firm creates value. That depth can take the form of short narratives, examples of improvements, insights about specific markets, or themes that tie the strategy together.

Photography matters too. Poor photos drag the whole site down. If the assets don’t photograph well, they shouldn’t be used. Real estate is a tangible category; when the assets look compelling, it gives the brand something private equity firms often don’t have.

Don’t: Let the Website Fall Behind the Times

Older websites look older because they are older. The signs are easy to spot: tight spacing, walls of text, small images, clunky grids, and typography that no longer feels contemporary. None of this reflects poorly on the strategy — but it does reflect poorly on the story.

Dated websites create cognitive dissonance. Visitors experience a disconnect between what the firm claims about its sophistication and what the website signals subconsciously. If the site feels neglected, the investor wonders what else might be neglected.

This is rarely fair, but it is real.

Don’t: Overload the Site With Irrelevant Detail

Many real estate managers treat their website like an offshoot of their pitchbook, which leads to pages jammed with copy, diagrams, and exhibits that belong in diligence, not discovery.

Permanent pages should not carry cycle-dependent language, interest-rate commentary, macro slides, or detailed operational processes. Those belong in investor materials or content pieces — not in the chassis of the brand. When the market shifts (and it always does), the site should not need rewriting.

High-level clarity is the goal. Detail belongs downstream.

Do: Avoid Speaking to Every Audience at Once

Trying to address institutional LPs, advisors, family offices, and HNW individuals all in the same paragraph is a recipe for noise. The firm does not need separate stories for each audience; it needs one strong story that each audience can interpret differently.

If a firm truly needs separate channels (for example, an institutional real estate fund and a non-traded REIT), then the solution is structural — separate pages or microsites — not layered messaging on the homepage.

Simple is stronger.

Do: Keep the Mobile Experience Tight

A surprising number of real estate sites still treat mobile as an afterthought, even though a large share of first visits come from phones. Poor mobile optimization reads as sloppiness — not because the investor consciously judges it, but because friction at the point of entry creates doubt everywhere else.

Clean spacing, readable text, fast load times, and modern motion cues all signal competence.

Don’t: Assume a Website Redesign Is the Only Option

Sometimes the highest-ROI improvement is not a full rebuild. For many firms, the fastest gains come from:

- replacing weak imagery with professional photography

- rewriting the homepage headline

- cleaning up the team page

- restructuring the portfolio grid

- updating the “About” page to match the firm’s current identity

- removing dense text that no one reads

- aligning pitchbook visuals with the site

These adjustments can carry the firm another year or two while a full redesign is planned.

But if the site has deep structural problems — outdated CMS, non-responsive layout, slow load times, or a visual identity that no longer fits the firm — it’s usually better to start fresh.

The Real Standard: Does the Website Reflect the Firm You Are Today?

Real estate managers don’t need dramatic originality in their website. They need something that reflects the maturity, discipline, and clarity of the organization they actually run.

Investors, advisors, and even transaction audiences look at websites with simple questions:

- Do these people seem organized?

- Do they seem credible?

- Do they know who they are?

- Does anything feel sloppy or outdated?

When the answers are positive, the firm gets a longer look. The work feels easier. The pitchbook lands better. Conversations open more smoothly.

When the answers are negative, most prospects never articulate why — they simply move on.

A great website won’t raise a fund. But a weak one can quietly undermine it. In a category where most sites look and feel the same, doing the basics well is still differentiation.

The Sameness Problem Runs Deep in Real Estate

Spend ten minutes browsing the websites of the top real estate managers by AUM and a pattern becomes obvious. The brands look similar. The language sounds identical. And the positioning frameworks rarely diverge from a short list of familiar claims.

This isn’t a coincidence. Real estate is a category where most firms are solving similar problems in similar ways. You can only talk about buying well, operating efficiently, and selling at the right time in so many permutations. But LPs are not evaluating firms in a vacuum. They are evaluating them side-by-side, and sameness makes the differentiation problem worse than it needs to be.

The central issue is not that real estate managers lack substance. It’s that the substance is rarely expressed in a way that feels distinct, memorable, or tailored to the strategy. And when LPs read the same phrases over and over, they begin to filter them out.

Why the Language Converges

Most real estate managers describe themselves using one or more of the following ideas:

- vertically integrated

- hands-on

- value-add

- conservative underwriting

- disciplined acquisition process

- proprietary sourcing

- data-driven decision-making

These are all reasonable descriptors. The problem is that they have been used so extensively that they no longer differentiate. They function as table stakes. LPs may believe these characteristics are present, but they do not interpret them as meaningful advantages.

One allocator put it to me directly years ago. When a client insisted we lead with “vertically integrated,” she said, “It’s not automatically a good thing. I need to know why the vertical integration exists and how it benefits the LP. It’s not the presence of the feature. It’s the quality of the explanation.”

That simple remark captures the broader challenge. Most firms rely on vocabulary that sounds institutional, but the institutional story isn’t actually being told.

Differentiation Comes From Depth, Not Labels

Real estate differentiation rarely comes from high-level concepts. It comes from:

- property type nuances

- geography-specific insights

- value-creation methodology

- operating sophistication

- technology enablement

- capital discipline

- deal sourcing edge

- team pedigree and history

Two managers may both say “value-add,” but one is talking about light unit upgrades in suburban multifamily, while another is talking about repositioning distressed industrial stock with a technology layer that reduces operating friction. The former sounds like everyone else. The latter tells a story LPs can visualize.

Real differentiation happens when you articulate the mechanism, not the label.

The Cyclical Nature of Real Estate Makes Positioning Harder

In many asset classes, differentiation is driven by strategy. In real estate, differentiation is driven by cycle awareness. What feels compelling in one year can feel stale or risky in another.

A manager in data centers today can lead with conviction. A manager in office must lead with thesis. A manager in shopping centers must lead with valuation. LPs expect managers to address cycle positioning early and directly. If you do not, they assume you have nothing to say.

This is why positioning cannot be static. The story must reflect:

- where your asset class sits in the cycle

- what contrarian or consensus view you hold

- how your approach mitigates the exposures LPs fear

- what the recent performance patterns imply

Real estate LPs do not want a generic explanation of the strategy. They want to know where the opportunity is now.

Why LPs Respond When You Go a Level Deeper

The managers who stand out are the ones who push beyond the industry’s shared vocabulary.

One of the more striking examples in recent years came from a self-storage platform we supported. They had an unusually sophisticated technology layer for property access and management. They had never articulated it clearly because they were used to raising capital from high-net-worth investors who didn’t require the detail.

When we reframed their narrative in a more institutionally credible way, the differentiation became obvious. The technology wasn’t a “feature.” It was a mechanism that reduced friction, reduced cost, and enhanced scalability. Once framed that way, the platform looked more compelling and more defensible.

This is the kind of detail LPs are looking for. Not new labels, but new clarity.

The Positioning Moves LPs Actually Notice

LPs may skim the first few lines of a deck or site, but they do retain certain signals:

- A thesis that is specific, timely, and clearly argued.

Not “we buy value-add multifamily in the Sunbelt,” but “we target mid-1980s suburban stock in markets where outmigration of workforce renters is slowing and supply constraints are rising.” - A brand expression that avoids developer cues.

If your materials feel like they’re advertising a single property, LPs assume you’re taking developer-like risk. - Details that illustrate operating edge.

If you know something your competitors don’t, show it. - A homepage or first slide that captures your actual strategy, not a generic category description.

This is where the tagline matters. It should express what is unique and ownable about your approach.

The Real Risk of Sounding Like Everyone Else

Sameness in real estate doesn’t just make you forgettable. It creates friction. LPs do not want to spend time deciphering your strategy. They do not want to guess how your value creation works. They do not want to assume your team is prepared for institutional scrutiny.

When your positioning is indistinct, LPs default back to the managers who have already earned their trust or have already built the scale that de-risks the relationship. Smaller and newer managers are the ones penalized most severely by sameness.

But the inverse is also true: smaller managers, when positioned well, can stand out more easily because they have more freedom to articulate a sharper tone of voice and a clearer point of view.

Breaking the Pattern

If you want to sound different in a category where everyone sounds the same, you must decide what is truly yours. That means identifying the specific intersection of property type, strategy, geography, and operating competency and turning it into a point of view that LPs can understand quickly.

When you articulate that clearly, LPs feel the difference immediately. They recognize coherence. They sense conviction. And they remember you.

Differentiation in real estate is not about inventing a new vocabulary. It is about telling the truth about what you do — with enough depth, clarity, and confidence that LPs realize they have not heard this explanation a hundred times before.

Real Estate LPs Decide Faster Than They Admit

In real estate fundraising, the first thirty seconds carry an outsized share of influence. LPs don’t think of this moment as a “decision.” They’re simply reacting — sorting, filtering, and trying to determine whether a manager fits the category, the cycle, and the credibility threshold they’re operating within.

Unlike private equity, where a charismatic founder or differentiated operating model can earn a second look, real estate LPs begin with something more primitive: Do I even want exposure to this asset type right now? If the property type, geography, or strategy is too far outside their mandate, the evaluation stops quickly.

My early IR experience at BKM Capital Partners taught me this firsthand. In 2014, multi-tenant industrial was not yet an institutional darling. Educating LPs took work. What ultimately broke through wasn’t a change in strategy; it was a change in presentation. The pitchbook, the PPM, the website — once those elements looked and read like institutional materials, LPs finally engaged the story. That lesson has stayed with me ever since.

What LPs Try to Learn Immediately

When an LP opens a deck or lands on a homepage, they’re trying to answer two questions almost subconsciously.

1. Does this strategy fit the mandate I have right now?

Real estate is more cyclical and sentiment-driven than any other asset class we touch. A Sunbelt multifamily fund in 2015 was considered a disciplined, defensive choice; by 2022, the same strategy carried very different risk optics. A contrarian retail or office thesis may be valid, but it needs to be articulated with clarity and conviction immediately.

In other words, LPs aren’t reading your story first — they’re reading the market first. And only then do they evaluate the manager.

2. Does this firm feel institutionally credible?

Real estate managers often come from development, acquisitions, or construction backgrounds. Their instincts are operational, not allocative. That is not a criticism; it’s part of the sector’s appeal. But it also means that narrative, design, and communication may not be instinctive.

LPs don’t expect a RE manager to look like a global PE firm. But they do expect:

- clear, modern materials

- a cohesive brand

- a website that doesn’t feel dated

- photography that elevates rather than diminishes the story

The first impression is not about gloss. It’s about whether the platform looks mature enough to be taken seriously.

Where Credibility Breaks in Real Estate Branding

Real estate managers unintentionally undermine themselves when their materials look more like a developer brochure than an investment manager identity.

Developer cues signal the wrong risks: entitlement, construction, timing. Unless the mandate is explicitly opportunistic, these are exposures LPs prefer to avoid.

This is why the firms who win the first thirty seconds present as investors, not builders. Their materials frame the strategy, the market context, the team, and the value creation approach before they ever show an asset.

The Sameness Problem — And Why LPs Tune Out Fast

Most real estate managers sound the same because they rely on the same familiar language:

- vertically integrated

- hands-on

- value-add

- proprietary sourcing

- data-driven

These phrases have been used so frequently they’ve lost meaning. They may be true, but they don’t differentiate. What LPs want to understand is how these attributes manifest in this specific strategy.

The managers who stand out go a level deeper. They talk about the actual mechanics of value creation — the technology layer in their operations, the underwriting nuance that others overlook, or the strategic advantage in a particular geography. Detail, not vocabulary, builds conviction.

Why the Website Matters More Than Managers Realize

Pitchbooks change annually. Websites last four to six years. That longevity makes the website the anchor of the visual brand.

It is also the most expressive medium real estate managers have. Color, typography, motion, and hierarchy shape the emotional impression LPs form before they evaluate a single number. And because many real estate sites skew dated — heavy text, template layouts, developer-style imagery — the bar for improvement is surprisingly low.

One of the best examples of a real estate brand that truly works is Hines. Their aesthetic is elegant, disciplined, and unmistakably institutional. Their use of a deep crimson as a primary color is a bold choice in a category that often avoids red. But it works because the entire system is coherent. It feels like the brand of a global manager.

This is what most firms miss. If you removed the property photos from your website, would anything distinctive remain? If not, you don’t yet have a brand — you have a template.

The Tagline and the Three Things LPs Remember

LPs will only remember a few things after an introductory interaction. The tagline and homepage language should encode those elements clearly. The line should reflect the unique intersection of property type, geography, value creation method, and team DNA.

This line will make tens of thousands of impressions over the life of the website and must carry enough specificity to stand apart from the crowd.

What LPs Want to Feel in the First Thirty Seconds

LPs aren’t looking for perfection. They’re looking for clarity and coherence. They want a strategy that fits their mandate and a manager who presents with enough maturity to justify deeper diligence.

Real estate fundraising is cyclical. Tastes change. Strategies fall in and out of favor. But the managers who consistently win early mindshare are the ones who understand that those first seconds of exposure are not superficial. They are establishing the frame through which the entire platform will be interpreted.

A strong brand doesn’t close the deal. It earns the meeting. And in real estate, that alone can be the difference between being considered and being forgotten.

The Truth About Logos

In investment management and private equity, logos are like names: places where clients tend to get overly fixated.

They’re emotionally charged artifacts — small enough for everyone to have an opinion, subjective enough for no one to be objectively right. We’ve seen entire brand-development projects stall for months because partners can’t agree on the exact line weight of a serif or whether the icon looks more dignified in navy or charcoal.

And yet, a logo is never what defines a firm. It’s an emblem, not an identity. It carries meaning only through the quality of the broader brand and the reputation built behind it.

Still, there are ways to get logos right — and more often, ways to avoid getting them wrong.

What a Logo Should (and Shouldn’t) Be

Within private equity and investment management, the visual bar is high. You’re selling trust, judgment, and long-term stewardship, not consumer products. A logo’s job is to support those associations quietly — not to draw attention to itself.

At the highest level, a good logo just needs to be quality work. In practice, that means:

- It’s well-crafted and consistent with the rest of your brand system.

- It has some degree of meaning, even if that meaning is oblique or abstract.

- It’s versatile — scalable, legible, and functional across every medium.

You don’t want a logo icon so intricate that it falls apart when reduced to a small size, or so horizontally long that it can’t fit gracefully on conference signage, a presentation cover, or a LinkedIn avatar. You also don’t want a logo that only works when every word of your firm’s name is spelled out.

The goal isn’t brilliance — it’s utility, elegance, and alignment.

The “Mailbox Before the House” Problem

Perhaps the biggest misstep we see — thankfully less often now — is the firm that says, “We’ve already got a logo, now we’re ready for a website.”

That’s like going to an architect and saying, “We’ve purchased a mailbox, and we’d like to design a house around it.”

It makes no sense.

What it tells us, almost every time, is that someone went to 99designs or a similar platform and paid $100 for a batch of freelance submissions. That process yields what you’d expect: commoditized, uninformed work that’s aesthetically random and strategically disconnected.

The problem isn’t just quality — it’s coherence. Those logos weren’t built with any understanding of the firm’s strategy, target investors, or story. They can’t possibly work as the centerpiece of a brand system because they were never conceived as part of one.

Why Craftsmanship Still Matters

A well-done logo has levels of sophistication, nuance, and restraint that most financial professionals, understandably, aren’t equipped to analyze. That’s why they often assume that more options, or more ornate designs, equal better outcomes.

But good identity design isn’t about novelty. It’s about proportion, visual rhythm, and the ability to scale across use cases without losing integrity. When people say, “Oh, I could get that on 99designs for $100,” they’re missing the point: you’re paying not for the drawing, but for the judgment behind it; the integration with color, typography, tone, and the overall architecture of the brand.

This is especially true in investment management, where credibility is conveyed through restraint. A good logo doesn’t shout. It suggests discipline.

Redrawing Without Rewriting History

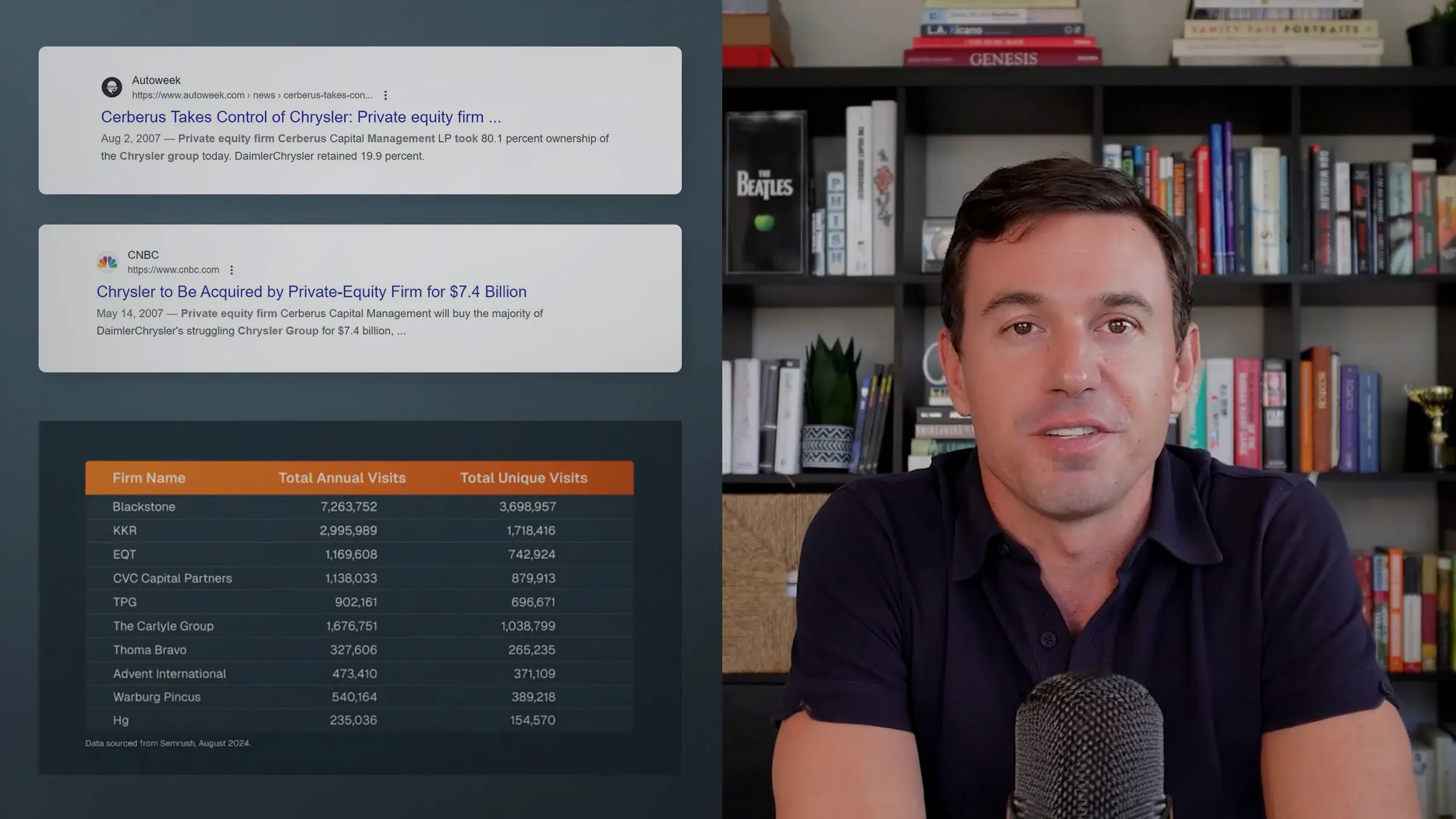

Though brand perception may seem intangible, it can be observed and influenced. Website analytics often reveal higher-than-expected traffic from diverse sources, and pitch materials circulate widely once shared. Even a modest 2% shift in perception — through a clearer pitch deck, an improved digital experience, or a refined narrative — can secure a significant allocation, win a competitive process, or attract a high-value hire. The potential compounding effect makes brand stewardship a high-leverage activity.

What Is the Bottom Line on Branding in Private Equity?

Brand in private equity is not a slogan or design exercise. It is the consistent, credible story a firm tells across all interactions, online and offline. In a market where many competitors offer similar returns and strategies, a well-managed brand can tilt decisions in your favor. The most effective brands are intentional, authentic, and aligned with how the firm actually operates — ensuring the story told externally matches the experience delivered internally.

Emerging managers tend to think their differentiation will appear once they’re in the room — once they explain the strategy, the sourcing edge, the underwriting muscle, the thesis they’ve spent years refining. But LPs form their first impressions in a far more primitive way. They differentiate before they understand. And almost always, that differentiation begins online.

What GPs often miss is that digital presence is not the packaging around the strategy. It is the earliest interpretation of the strategy. And when everyone in a given category sounds more or less the same on paper — disciplined process, proprietary deal flow, conservative leverage, operational value creation — the website and the digital footprint become some of the only places where a story can meaningfully diverge.

Emerging managers underestimate how much room they actually have to be distinct. The irony is that the early-stage firms who could most benefit from differentiation often constrain themselves into visual and narrative templates that make them look like smaller versions of their older competitors. They take all the possibilities of being new and compress them into something unremarkable.

1. Differentiation Begins Emotionally, Not Analytically

Before LPs think about a fund, they feel something about it. This is hard for managers to internalize because they live in the world of thesis development, sector analysis, and operational playbooks. LPs live in the world of cognitive triage. They are meeting dozens, sometimes hundreds, of managers each year. They cannot begin each relationship from scratch.

So they differentiate instinctively:

- Does this feel fresh?

- Does this feel disciplined?

- Does this feel like a firm that knows exactly where it sits in the category?

- Does this feel like the beginning of something interesting?

That emotional reaction comes from the digital presence — not from the pitchbook. Your digital identity is the rough categorical judgment that determines whether an LP enters the meeting curious or skeptical. It shapes the altitude at which they listen. And that can be the difference between a conversation that feels like discovery and a conversation that feels like scrutiny.

2. New Managers Have a Natural Differentiator — and Most Don’t Use It

One of the unspoken advantages emerging managers have is that LPs want them to be different. The incumbents have had decades to calcify their processes, their cultures, their worldviews. LPs know how those firms think. What they don’t know — and what they often find refreshing — is how someone new might think.

In the arts, the most exciting filmmakers aren’t usually the ones with thirty years of credits. They’re the ones bringing a sharper, newer sensibility to the medium. Emerging managers have the same opportunity. Their digital presence should acknowledge this possibility. It should feel modern, confident, and alive in a way that legacy firms cannot convincingly mimic.

But many emerging managers default to a conservative aesthetic because they fear seeming inexperienced. In doing so, they erase the exact newness that LPs find most intriguing.

You don’t differentiate by looking older. You differentiate by looking formed.

3. Specificity Is the Real Differentiator — Digital Design Just Helps You Express It

Every emerging manager believes their strategy is specific. But specificity doesn’t differentiate unless it’s visible. Digital presence forces visibility. It shows whether:

- the category is clearly defined,

- the angle feels sharp,

- the edge is articulated rather than asserted,

- the story is portable enough to travel through an institution.

Great digital presence doesn’t produce differentiation. It reveals it.

A website that says, in effect, “We operate in a niche you’ve almost certainly underestimated — and here’s why it matters,” creates a different experience than a website that tries to be a small version of a multibillion-dollar fund. LPs don’t remember the firms that imitate incumbents. They remember the ones that sharpen their shape.

4. Digital Coherence Signals Strategic Coherence

What LPs interpret as “differentiation” is often subtler than managers think. They look for signs that the GP’s point of view is stable across mediums — website, deck, bios, content, digital profiles. When the tone is consistent, the language is consistent, and the design system is consistent, LPs assume the strategy itself is consistent.

Conversely, when the digital footprint feels improvised — mixed styles, mismatched language, stray metaphors — they assume the edge is not fully formed.

This is not a conscious judgment; it’s pattern recognition.

A digitally coherent emerging manager stands out simply because the market is full of firms presenting three or four different versions of themselves. LPs respond instinctively to a firm whose worldview appears settled.

5. Content Is the Most Underused Differentiator of All

Emerging managers have a huge opportunity here because most of their peers publish nothing. A small collection of thoughtful pieces — longform, video, or otherwise — signals three things:

- The manager has a genuine point of view.

- They understand their category at a deeper level than the pitchbook shows.

They are willing to put their name behind ideas.

This doesn’t require volume. Ranchland Capital didn’t publish constantly. They published well. Their content wasn’t marketing — it was evidence. LPs interpreted it as seriousness, and perhaps more importantly, as clarity. Nothing differentiates an emerging manager more quickly than clarity.

The added bonus:

Content becomes part of your LLM footprint.

And in the coming years, LPs, intermediaries, and sellers will increasingly use LLMs as filters.

If your name and your category-specific thinking are connected digitally, your differentiation compounds.

Closing Thought

Differentiation is not something you announce in a tagline. It is something you signal through every digital decision you make. Emerging managers who understand this use their website and digital presence to create early impressions of sharpness, coherence, and newness — qualities LPs crave but rarely find. You differentiate not by shouting your edge, but by designing a digital identity that makes the edge feel inevitable.

Emerging managers often think differentiation begins in the meeting. It doesn’t. It begins when the LP first sees you — and decides whether you might be the most interesting new director in the category.

In real estate, the way materials look and feel is often dismissed as a matter of taste — aesthetic preference, graphic design polish, the “marketing gloss” that sits on top of the actual investing work. But investors do not experience materials this way, and they never have. They read documents as a direct reflection of how the organization works.

Clean, consistent, well-structured materials signal discipline.

Sloppy, inconsistent materials signal disorganization.

And real estate — more than many asset classes — lives or dies on an investor’s confidence in the manager’s discipline.

This is not a superficial relationship. It’s structural. Documents are, for most investors, the only window into the firm’s internal operations. They cannot see your underwriting meetings. They cannot see your property walks. They cannot sit in on debt negotiations or asset management reviews. They infer your discipline from the artifacts you share.

Which means document quality is not cosmetic. It is operational.

1. Investors Judge the Process by the Presentation

Investor materials — pitchbooks, updates, property snapshots, reporting packages, advisor decks, and even basic fact sheets — are proxies for how the manager works. If a deck arrives organized, crisp, and coherent, investors assume the same discipline exists behind the scenes. If a deck feels messy, dated, or disjointed, investors instinctively assume that something inside the operation may also lack cohesion.

They are not consciously making this leap, but they are making it nonetheless. The psychology is simple: if the materials are sloppy, what else might be sloppy?

This assumption may not always be fair, but it is consistent. Investors see hundreds of documents each year. They do not have time to investigate whether the disorganization in your materials is merely cosmetic. They simply choose to spend more attention on managers who look like they have their house in order.

Document quality is a trust signal, not a design exercise.

2. Professional Design Is Not Luxury — It’s Table Stakes

There is a vast and obvious difference between materials assembled by someone in-house “who knows PowerPoint” and materials built by someone trained to produce institutional-grade communication. Managers often underestimate this difference because they see their own content too closely. They know what the slide is trying to say, so they assume the investor will understand it too.

But investors see the surface first.

Clean typography, clear hierarchy, integrated charts, aligned margins, consistent icons, modern layouts, and readable spacing are not decorative. They make the information interpretable. They reduce friction. They make the deck skimmable and trustworthy. In a category where many managers underinvest in communications, these elements also differentiate.

And they do not have to be expensive. Professional design is widely accessible, but it does require intention. When a deck looks like it was built a decade ago, or in a rush, or copied from an outdated template, investors recoil. They may continue reading out of obligation — but they do not feel the same confidence.

Real estate managers do not need ornate design. They need clean design.

3. Clarity Signals Maturity

A surprising percentage of real estate materials fail not because of design, but because of density. Walls of text. Overloaded slides. Process diagrams that try to say everything. Track record tables that feel like spreadsheets pasted into PowerPoint. Market commentary that reads like a consultant report squeezed onto a slide.

Investors rarely read these slides. More importantly, they do not interpret them as “thorough.” They interpret them as unclear.

Clarity requires restraint.

It requires knowing what must be said, what can be trimmed, and what should be moved to an appendix. It requires clean headlines that act as thesis statements, not labels. It requires a point of view. Managers who achieve this level of clarity appear more seasoned, more confident, and more aligned.

Maturity is not how long the firm has been operating. It is how coherently the firm communicates.

4. Consistency Builds Brand Memory and Reduces Friction

Most real estate managers are not producing one set of materials. They are producing dozens: pitchbooks, quarterly updates, market notes, property snapshots, deal announcements, advisor packets, 4-pagers, fact sheets, and internal follow-ups. When each document looks slightly different — different fonts, different colors, different slide styles — it creates visual noise. Investors feel the inconsistency even if they cannot articulate it.

Consistency builds familiarity.

Familiarity builds trust.

Trust reduces the friction of each new investor touchpoint.

When materials share a unified design system, a unified tone, and a unified narrative rhythm, each new document reinforces the last. The investor never feels like they are re-learning the identity of the manager. Instead, the manager feels stable and intentional.

Consistency is its own form of professionalism.

5. Design Discipline Helps Investors Understand the Strategy

Document quality is not about aesthetics. It is about helping the investor understand the story with minimal effort.

Real estate strategies often involve complex moving parts — sourcing, acquisition, underwriting, operational improvement, leasing, capital programs, refinancing, and disposition. When these components are cluttered, visually inconsistent, or explained in a rushed manner, investors struggle to follow the logic. They mentally downgrade the strategy not because it is weak, but because they cannot see its structure.

A well-designed slide can reveal structure at a glance:

a clear sourcing funnel, an intuitive value-creation model, a logical case study, a concise market thesis, a readable portfolio summary. These visuals are not “prettification.” They are communication.

Design is the medium that turns complexity into comprehension.

6. Quality Matters Across Every Vehicle Type

Document discipline is not optional in any part of the real estate universe.

Closed-end funds:

Investors expect pitchbooks, market commentary, and updates that feel coherent quarter to quarter.

Non-traded REITs:

The advisor and wealth channels require materials that are skimmable, direct, and retail-appropriate.

Interval funds:

NAV updates and performance packets must be readable at a glance.

1031/721 platforms:

Property-level updates must elevate, not obscure, the investment story.

Family-office vehicles:

Bespoke reports need to feel tailored without feeling improvised.

Across structures, the expectation is the same: make it easy to understand what is happening and why it matters. Document quality is central to that task.

7. Where DG Supports the Document Layer

For most real estate managers, document production becomes a bandwidth challenge long before it becomes a design challenge. Teams are stretched. Deadlines are tight. Updates arrive at inconvenient times. Materials must evolve as the portfolio evolves. And consistency is difficult to maintain without a dedicated communications function.

DG fills that capability gap.

We help teams standardize their materials, modernize their design language, build templates, produce updates quickly, and refine the narrative structure underlying all ongoing communication. For many clients, DG becomes the “continuity layer” that keeps materials aligned even as the firm grows or diversifies.

The value is not in making documents beautiful.

The value is in making them coherent, credible, and immediately legible to the people who make capital decisions.

Closing Thought

In real estate, documents are not decoration. They are the visible expression of how the organization operates behind the scenes. A manager who communicates with clarity and consistency looks disciplined. A manager who updates materials regularly looks engaged. A manager who invests in document quality looks confident in the story being told.

Investors may not articulate these reactions, but they feel them instantly. Document quality is not cosmetic. It is operational — and one of the clearest signals of who a manager really is.