.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Across the real assets investment world, a structural shift is unfolding quietly but decisively. Managers who once behaved like conventional real estate or infrastructure investors are now applying the logic, cadence, and rigor of private equity to businesses anchored in physical assets. They are underwriting management teams, designing governance, building platforms, and focusing on long-term cash flow development rather than incremental yield. Internally, these firms operate with a degree of sophistication that blends PE, credit, and real asset expertise into a single, adaptable model. Externally, however, many still describe themselves in terms that no longer capture what they actually do. The result is a widening gap between internal identity and external perception.

The Shift From Asset Selection to Business Building

Within these firms, value creation is driven less by asset selection and more by what the business does with the asset. Investors are focusing on operational design, scalable systems, margin improvement opportunities, management capability, and the eventual attractiveness of the platform at exit. The underwriting lens has broadened far beyond the characteristics of the underlying real estate. What matters now is the revenue model, the durability of cash flows, and the ability to compound operational progress over time. This evolution mirrors private equity’s approach, yet most firms still describe their work with language borrowed from traditional real estate disciplines. Their public identities remain rooted in asset allocation even though their internal models resemble platform building with real asset intensity.

The Cross-Cycle Orientation That Traditional Messaging Cannot Express

Another defining characteristic of this new class of investors is their ability to remain active across market cycles. They move between equity and credit depending on conditions; they pursue growth platforms when markets are stable and structured opportunities when markets reset; they underwrite intrinsic value with discipline across multiple entry points. Internally, this flexibility is methodical rather than opportunistic, made possible by teams whose experience spans several parts of the capital structure. Yet when firms attempt to explain this externally, they often rely on the familiar phrase “investing across structures,” a description that captures breadth but misses the intentional design behind it. These firms are not improvising. They are engineered for persistence and adaptability, but their messaging rarely communicates this intent.

Thematic Research as a Strategic Engine

The most sophisticated firms rely on multi-year thematic work to direct sourcing and value creation. Their themes are not loose interpretations of broad trends, but structured, deeply researched viewpoints about how specific types of assets are used and monetized within the broader economy. A strong theme influences not only what the firm buys, but how it plans to scale the business, what the future buyer will require, and which operational levers matter most. Despite the weight of this work, thematic discipline is often summarized in only a few words. Without context, the concentration that defines the strategy can appear risky; the deliberate pacing can be mistaken for limited opportunity; the depth of research can be confused with slogan-level positioning. The rigor behind the strategy is clear internally but disappears in the external narrative.

The Cohesion Challenge Inside Newly Assembled Teams

Many firms pursuing this hybrid model are young in vintage but institutional in structure. Their teams are composed of professionals from private equity, credit, restructuring, operations, and real assets. The diversity is intentional, designed to sharpen underwriting and broaden the opportunity set. However, in the absence of a clear explanation, the market tends to interpret new teams as untested or inconsistent. First-time funds face this challenge most acutely. Without a well-designed message that articulates why the team is built the way it is, how viewpoints converge, and how decisions are made, the market assumes fragmentation where cohesion actually exists. The issue is not with the team itself. It is with the interpretation of the team.

Why External Identity Falls Behind Internal Evolution

The most consistent pattern across these firms is simple: the internal strategy evolves faster than the external identity. The firm becomes more complex, more disciplined, and more capable, yet the way it presents itself remains anchored in earlier definitions. Public materials still emphasize asset-level characteristics even when the investment model depends on platform development. The tone still mirrors real estate managers even when the underwriting resembles private equity. The website still describes a narrow mandate even when the firm is designed to function across cycles. Without a structured explanation of what the firm actually is, the market defaults to outdated categories. Misinterpretation occurs not because the strategy is unclear but because the message is incomplete.

Conclusion: A New Category Needs a New Explanation

A growing set of firms now operate at the intersection of real assets, private equity, and credit, yet the language available to describe them remains limited. These firms underwrite operating businesses with real asset foundations. They design multi-cycle strategies and balance-sheet approaches rather than single-cycle bets. They rely on thematic frameworks, cross-functional teams, and long-term operating design to unlock value. Their identities are not captured by existing labels, and until they articulate the internal logic that unifies their strategies, they will continue to be misunderstood through the lens of legacy categories. The strategy is new. The teams are new. The operating approach is new. What is missing is the vocabulary. Once firms define that vocabulary for themselves, the market will finally see the model for what it truly is: a distinct, emerging category that deserves its own explanation, rather than a variation of the categories that came before.

When LPs evaluate an emerging manager, they are rarely reacting to a single document. They are reacting to an ecosystem of documents — the pitchbook, the data room, the bios, the case studies, the quarterly updates, even the filenames and the metadata. None of these elements, on their own, determine whether an LP will invest. But together, they shape a subtle and surprisingly durable impression of the organization behind the strategy. For Fund I and Fund II managers, that impression often forms before the LP has spent more than a few minutes with the material.

Emerging managers tend to think of “materials” as the pitchbook itself. LPs interpret materials as behavior — evidence of how the GP thinks, how the GP organizes information, and how the GP might operate once entrusted with capital. The deck is only the beginning of that story.

1. LPs Notice How Carefully (or Carelessly) Materials Are Packaged

Before an LP reads a single slide, they notice how the materials arrive. Was the deck attached cleanly? Is the filename human or machine-readable? Does the email preview make sense? Does the pitchbook open to a coherent cover slide, or does it reveal a disordered first page that looks like it was stitched together the night before?

These details seem trivial, but they are not. They are early signals of whether the GP has a habit of thinking cleanly. LPs know perfectly well that emerging managers are stretched thin — wearing three or four hats, building the firm as they raise the first institutional capital. But precisely because of that, clarity in the early materials stands out. When the packaging is thoughtful, LPs assume the process behind it is thoughtful. When the packaging is sloppy, LPs assume the GP will require handholding down the line.

2. The Data Room Is a Quiet Testament to Operational Discipline

LPs rarely compliment a data room. They only notice it when something is wrong. A well-organized data room feels like a natural extension of the pitchbook: the categories make sense, the documents load cleanly, the naming conventions are consistent, and nothing feels like filler. A chaotic data room — mismatched labels, duplicate files, inconsistent versions — tells LPs something they cannot unsee. It’s not a story about effort; it’s a story about process.

Emerging managers sometimes treat the data room as “a place to put things,” rather than as an expression of how they manage information. LPs are evaluating the data room not just for content but for care. They know what a mature organization looks like on the inside. A coherent data room is one of the easiest ways to simulate that maturity early.

3. Writing Style Across Materials Is a Psychological Signal

LPs do not expect emerging managers to be literary stylists. But they do expect writing that is clear, confident, and consistent. When the pitchbook sounds one way, the website sounds another, and the bios sound like they were assembled by three different people, LPs feel narrative instability long before they articulate it.

Writing is a trust signal. It shows whether the GP can describe their own strategy with clean edges. It shows whether the team is aligned on its worldview. And because Fund I decks are shorter than Fund VII decks, the writing has to work harder. You cannot hide behind volume. If an LP senses hesitation in the writing — excessive jargon, vague claims, inconsistent tone — they assume the thinking itself may be tentative.

This is not always true, but LPs have trained themselves to read materials this way. They have to; they don’t have time for deeper analysis until later.

4. Case Study Behavior Reveals Whether a GP Knows What LPs Care About

LPs read case studies for a single purpose: to understand how the strategy behaves in the real world. But many emerging managers use case studies to demonstrate how impressive an asset was, not what they actually did. They over-index on describing the company or property, and under-index on the value creation during the hold. LPs want the reverse.

When a case study opens with paragraphs about the company’s headcount, geography, or operational complexity, LPs begin skimming. When a case study opens with a crisp articulation of the thesis, the intervention, and the outcome, they pay attention.

The way a GP builds case studies shows whether they know what matters. LPs infer judgment not from the success of the example but from the clarity of its telling.

5. LPs Look for Consistency Across Materials — and Notice Its Absence Immediately

Emerging managers often update their pitchbook more frequently than their website, or their introductory email more frequently than their bios. LPs see these mismatches instantly. They are not just evaluating what the materials say; they are evaluating whether all the materials say the same thing.

Consistency signals alignment. It shows that the GP has a stable identity, a settled point of view, and a strategy that has survived the first wave of iteration. Inconsistent materials tell LPs that the story is still forming — which is fine in Month 1, but less fine in Month 18 when the fundraise is underway. LPs don’t need the materials to be perfect. They need them to agree.

Closing Thought

Emerging managers tend to focus on the pitchbook as if it were the centerpiece of the story. LPs evaluate something broader: the behaviors revealed through the materials ecosystem. The deck, the data room, the writing, the consistency, the attention to detail — all of it becomes a composite picture of whether the GP is ready for institutional partnership. In Fund I fundraising, this composite picture forms much earlier than most managers assume. And for LPs, that picture is often the difference between “interesting” and “investable.”

Most emerging managers believe they have a narrative because they can describe their strategy. But narrative is not description. Narrative is structure — the sequence, logic, and emotional progression that allows an LP to understand why a category matters, why a particular angle makes sense, and why this manager might be worth backing. A pitchbook is the first time an emerging manager is forced to express that structure outside of conversation, without the ability to clarify, expand, or recalibrate in real time. It exposes whether the story has bones or whether it’s being held together by enthusiasm and improvisation. And for Fund I and Fund II managers, narrative structure is often the difference between a deck that feels like the beginning of a real institutional story and one that feels like a loose collection of ideas.

1. A Strong Fund I Narrative Begins With Category, Not Credentials

Emerging managers frequently begin their pitchbooks by describing themselves: bios, backgrounds, decades of combined experience. But LPs don’t have the frame yet. They don’t know what the team is applying that experience to. Narrative structure starts one level higher — with the category. What is the space you operate in, and why is it worth anyone’s attention? In an early-stage deck, the category is not assumed; it has to be established cleanly. If LPs don’t understand the world you’re investing in, they won’t know how to interpret anything that follows. The category sets the altitude. And in Fund I fundraising, altitude determines whether the rest of the narrative ever lands.

2. The Strategy Must Feel Like the Natural Response to That Category

Once the category has been framed, the strategy has to emerge as the logical next step — not as a standalone set of tactics. LPs want to feel a sense of inevitability: given the structure of this market, here is the approach that makes the most sense. This is where emerging managers often lose momentum. They describe a strategy with plenty of detail but very little connective tissue. There’s no narrative bridge from “here’s the opportunity” to “here’s the right way to pursue it.” Good narrative structure makes the strategy feel like the only sensible response to the category you just described, not one of many plausible approaches floating in conceptual space.

3. Sequencing Is a Psychological Tool, Not a Formatting Choice

The order of slides is not an aesthetic decision; it’s a cognitive decision. When you open a deck with a track record — even a good one — the LP has no idea what that track record means yet. They lack context: track record for what? Similarly, when you lead with a process diagram, the LP doesn’t know why the process matters. They haven’t been taught the dynamics of the market or the underlying thesis. This is why the executive summary belongs first, then the category, then the strategy, then (and only then) the credentialization. Emerging managers who get sequencing right create narrative momentum; those who get it wrong force the LP to hold disconnected ideas in their mind and assemble the story themselves. LPs rarely choose to do that work.

4. Effective Pitchbooks Use Examples to Make the Strategy Tangible, Not Decorative

Emerging managers often struggle with how to incorporate examples — prior deals, pre-fund deals, warehoused assets, or selected historical experience from earlier firms. The instinct is to throw the examples into the middle of the deck or to use them as early-stage “proof.” But examples are not proof; they are narrative illustration. Their job is to show what the strategy looks like in the real world and to give texture to the thesis. When examples appear too early, they feel orphaned from the story; when they appear too late, they feel like an afterthought. When examples appear right after the strategy section, they reinforce the thesis and make the story concrete. LPs stop seeing a theoretical angle and start seeing an investable one. That shift — from abstract to tangible — is where narrative structure begins to create memory.

5. Narrative Structure Lives or Dies in the First Five Slides

Every emerging manager believes LPs will “get to” the important part. LPs don’t get to anything. They skim, they flip, and they decide whether the story is worth tracking. The first five slides are the narrative’s opening scene. If the opening doesn’t establish the category, the angle, and the promise of the story, the LP rarely reads far enough to see the nuance. Think of it as the pilot episode of a television series: you don’t get eight hours to win someone over. You get 40 minutes. Emerging managers who bury the thesis halfway through the deck are essentially asking LPs to wait until episode eight before it gets good. Nobody does that anymore.

Closing Thought

Narrative structure is what makes a pitchbook coherent, memorable, and emotionally legible. Emerging managers often mistake narrative for polish. But LPs don’t respond to polish; they respond to clarity. They want a story that makes sense on its own terms, that emerges in the right order, and that gives them enough structure to evaluate the idea without doing interpretive work. The pitchbooks that succeed aren’t the ones with the best diagrams or the most slides. They’re the ones that teach the LP how to think about a category, an angle, and a team — in a way that feels unmistakably intentional.

If you read enough emerging manager pitchbooks, they begin to feel strangely interchangeable. Different strategies, different sectors, different pedigrees — but somehow the materials converge into a common aesthetic and a common voice. It isn’t because emerging managers have nothing distinct to say. It’s because the form they’ve inherited suppresses the distinctions without anyone realizing it. The PE spinout copies the institutional conservatism of their old platform; the real estate entrepreneur imitates a property OM; the credit manager defaults to a PPM tone. In all cases, the material becomes so familiar that the strategy itself struggles to stand out.

1. Inheriting Someone Else’s Template Is the First Differentiation Trap

Many private equity spinouts begin their pitchbook by copying what they last saw at a mature firm. It makes sense emotionally — that format feels “correct.” But Fund VII materials exist for a different psychological condition. Those decks are meant to continue a long narrative, not start one. When a Fund I manager adopts the same tone and architecture, they unintentionally shrink their own story into a template meant for incumbents. It’s like borrowing somebody else’s suit for a debut performance: technically functional, but the wrong identity. Emerging managers need to own their newness, not camouflage it in legacy formatting.

2. Real Estate Managers Often Miss in the Opposite Direction

If PE spinouts tend to be too conservative, real estate emerging managers often skew too loose. Their pitchbooks resemble single-asset offering memoranda or disclosure-heavy PPMs. They lead with property-level detail, scatter long lists of amenities or operational characteristics, and forget that an LP is not buying a property — they’re evaluating a strategy. The result is an unintentionally blurry picture. The LP never receives the sharp definition of what the manager actually does. Differentiation disappears beneath a pile of specifics that don’t speak to the thesis.

3. The First Five Slides Determine Whether You’re Memorable

Differentiation doesn’t begin on slide twenty. It begins on slide one. LPs skim. They flip. They decide whether the story has any shape worth investing attention into. Those opening slides must articulate the category, the angle, and the reason the angle is compelling right now — all before the reader has to work. But too many emerging managers use their early slides for process diagrams, team bios, or flowcharts that could have come from any manager in the category. Nothing gets anchored. Nothing sticks. When LPs cannot remember what makes you distinct after five slides, they will not keep flipping in search of something to hold onto.

4. A Point of View Differentiates More Than a List of Strengths

Most pitchbooks differentiate via lists: sourcing networks, thematic expertise, operating capabilities, disciplined underwriting. LPs see these lists constantly, and they rarely remember them. What stands out is a point of view — a way of framing the category that feels specific, lived-in, and genuinely yours. Differentiation does not require novelty. It requires clarity. When a manager can say, “Here is how this corner of the world actually behaves, and here is why our angle matters,” LPs perk up. When the manager defaults to the same sanitized language as every established fund, they disappear instantly. A point of view is the most renewable form of differentiation an emerging manager can have.

5. Track Record Differentiates Only When It Fits Into the Story

Most emerging managers cannot port attribution from prior firms. LPs know this. They aren’t asking you to perform cartwheels to make history do more than it legally can. What they want is texture: examples that show how you think and how the strategy behaves in the real world. Whether those examples are pre-fund deals, warehoused assets, or carefully contextualized prior work, they differentiate only when they reinforce the narrative. A good deal example doesn’t say “look how impressive this company was”; it says “here is what we did and why it mattered.” When examples support the angle — rather than distract from it — they become a differentiator, not a filler.

Closing Thought

Most emerging managers are not suffering from a lack of substance. They are suffering from a lack of contrast. Differentiation in materials doesn’t come from clever visuals or a new arrangement of bullet points. It comes from a point of view that can’t be mistaken for anyone else’s and from an early structure that reinforces that view. The pitchbooks that rise above the commodity pile aren’t necessarily the flashiest. They are the ones that feel like the first chapter of a story only one manager could tell — and that LPs would be annoyed to forget.

Every real estate manager knows that markets move in cycles. Some phases reward activity; others punish it. Some invite capital; others repel it. Interest-rate environments shift, valuations reset, sentiment swings, and property types move in and out of favor for reasons that are both structural and psychological. None of this is new.

What has changed is the communication pressure around those cycles. Investors now expect managers to articulate not only what is happening, but what it means — and to do so with calm precision, even when the market itself feels anything but calm. Whether the investor is an institution, a family office, an advisor, or an individual, the expectation is consistent: communicate clearly, consistently, and without dramatizing or downplaying conditions.

In real estate, this expectation is especially acute because the asset class is tangible. Even investors who don’t live inside the mechanics of property management have intuitive reactions to vacancy, interest rates, debt costs, or headlines about multifamily distress. The more they can imagine the underlying assets, the more they want to understand the manager’s interpretation of the environment.

Communicating through cycles is not about predicting outcomes or smoothing over volatility. It is about framing the environment, reinforcing discipline, and helping investors understand how to interpret what the manager is doing.

Done well, cycle communication builds credibility.

Done poorly — or inconsistently — it creates questions that linger long after the market stabilizes.

1. Investors Don’t Expect You to Control the Cycle — They Expect You to Interpret It

One of the most common mistakes managers make during difficult cycles is assuming that investors want reassurance or certainty. In reality, investors want clarity. They want a grounded explanation of the environment, not a forecast. They want to understand how the manager sees the current phase and how that perspective informs decision-making.

Investors are not evaluating whether a manager “called the cycle.” They are evaluating whether the manager thinks coherently about uncertainty. Even a brief quarterly update or webinar note that cleanly frames what is happening — without melodrama and without euphemism — often reassures more effectively than any optimistic projection.

In this sense, communication is not about eliminating uncertainty; it is about giving investors a reliable vantage point from which to observe it.

2. The Market View Must Feel Calm, Specific, and Integrated with Strategy

The most effective market commentary during a cycle shift has three characteristics: it is calm, it is specific, and it connects directly to the manager’s strategy.

A calm tone signals discipline.

Specificity signals competence.

Integration signals intentionality.

When managers present the macro environment as an isolated slide or letter — separate from sourcing, asset management, or value creation — it feels abstract. When they integrate the macro view with the strategy (“This is where we are, and here is how that affects how we operate”), the narrative becomes coherent.

Investors don’t need — or want — a dissertation. They want a manager to demonstrate command over the inputs that matter: rates, valuations, supply-demand dynamics, absorption, operating cost pressures, liquidity conditions, and whatever is uniquely relevant to the property type.

The goal is not to be predictive. The goal is to show that the manager is awake.

3. Storytelling Must Adapt to the Cycle Without Reinventing Itself

A cycle shift does not require a new identity. It requires a shift in emphasis.

When markets are strong, the narrative often emphasizes opportunity, capacity, and growth. When markets contract or stall, the narrative should emphasize discipline, underwriting rigor, operational excellence, and selective conviction. When markets transition — perhaps the most delicate moment — the narrative must balance patience with preparedness.

Managers sometimes overcorrect in both directions. They either pretend nothing has changed or they build an entirely new story that contradicts the one investors originally bought into. Investors see through both approaches.

A disciplined communication framework allows a manager to evolve the emphasis — without abandoning the core strategy or confusing the investor about who the firm is.

Cycle communication is, at its core, an exercise in intelligent reframing.

4. Consider the Full Spectrum of Audiences When Communicating Cycles

Cycle communication is not one-size-fits-all. Institutions, family offices, advisors, and individuals interpret the environment differently.

Institutions tend to evaluate cycle commentary through the lens of risk management and positioning. They want to understand how the manager is thinking about leverage, valuations, and deployment windows. Family offices value directness and often respond to clear articulation of where the manager sees opportunity or caution. Advisors need materials they can pass on to their clients — concise, accessible, and grounded. Individuals often react most strongly to tone: confidence without bravado, realism without pessimism.

A manager doesn’t need to create separate narratives for each group, but the communication should be written with an awareness of these differences. A single message can resonate across audiences as long as it is structured, digestible, and balanced.

5. Communication During Difficult Markets Has a Multiplier Effect

When markets tighten, investors become more sensitive to clarity, not less. They engage more closely with updates, ask more questions, and evaluate more carefully whether the manager is handling complexity thoughtfully.

Managers who communicate well during difficult periods often develop stronger investor relationships than managers who happen to raise during easy periods. Investors remember calm leadership — and they remember who disappeared.

Cycle communication becomes a competitive differentiator because it builds emotional and psychological trust, not just informational trust. Investors don’t expect perfection. They expect presence.

When the next capital formation phase begins, investors who have been consistently oriented are far more ready to recommit or increase exposure.

6. Where DG Supports the Cycle Narrative

Cycle communication requires judgment, structure, and a steady editorial voice — qualities that many teams don’t have the bandwidth to produce internally while managing the portfolio itself.

DG’s role is to help managers articulate the cycle without overstating or understating it. That includes refining quarterly or periodic letters, developing webinar scripts, preparing slides that frame the macro clearly, and ensuring that the visual and narrative identity remains intact even as the emphasis shifts. We help managers express the right amount of detail for each audience, sequence the story, and maintain coherence across updates.

Cycle communication is one of the clearest examples of how professional support elevates a platform. The content may come from the manager, but the clarity, rhythm, and precision often come from the partnership.

Closing Thought

Real estate markets will always move in cycles. What investors evaluate is not whether a manager avoids the downside or perfectly times the upside, but whether they communicate responsibly, consistently, and with conviction shaped by reality rather than emotion. Good communication will not eliminate volatility, but it will sustain trust through it.

Managers who view cycle communication as part of their brand — not just part of their reporting — create resiliency that carries forward into every future phase of capital formation.

Emerging managers don’t fundamentally misunderstand pitchbooks. Most of the people who make it to Fund I are rational, competent, and thoughtful. The problem isn’t intelligence; it’s framing. They’re building decks as if LPs were primarily evaluating the information, when in reality LPs are evaluating the story around the information — and, more specifically, whether that story feels investable for a first- or second-time fund.

From an LP’s perspective, a Fund I or Fund II pitchbook isn’t an encyclopedia. It’s a test. It answers three questions very quickly:

- Is this a real firm or a concept in motion?

- Is there a coherent way to think about this strategy?

- Is there anything here I’ll remember tomorrow?

Most early decks fail one of those tests, and usually for avoidable reasons.

LPs Don’t Want a Miniature Version of a Fund VII Deck

One of the most common mistakes I see is spinouts copying their former employer’s materials. A manager leaves a large platform, takes the Fund VII deck as a mental template, and tries to shrink it into a Fund I format. It doesn’t work.

Fund VII decks are designed to situate a new vehicle inside a 20–30 year arc:

here’s where we’ve been, here’s how we’ve performed, here’s how the strategy has evolved, here’s what’s different this time. LPs reading those decks already know the franchise. They need context.

Fund I decks have the opposite job. There is no arc. There is no franchise history. The LP isn’t asking “how has this strategy evolved?” They’re asking “what exactly is this, and why should I care?”

Those are radically different questions. Using a Fund VII blueprint for a Fund I pitchbook is like using a retirement speech outline as a template for a debut.

The First Five Slides Are the Real Deck

LPs don’t read pitchbooks linearly the way managers imagine. They skim, they flip, they pause, they decide whether to keep going. In that sense, the first five slides are the deck. Everything that comes after is optional.

What LPs need out of those opening slides is simple:

- a clear explanation of the category,

- an understandable angle,

- and a sense that the manager knows exactly what they’re trying to build.

Too many emerging managers use their early slides for a deal funnel graphic, an investment process diagram, or a collage of buzzwords. No one has ever become excited about a new manager because they saw a diagram showing “proprietary deal flow” and an arrow labeled “value creation.”

If a reader doesn’t understand what you are, where you play, and why your angle is interesting within five slides, they usually don’t keep going. It’s like a new TV show: if the first episode doesn’t land, no one is waiting until episode eight for it to “get really good.”

LPs Want Category Education and Ownership of the Angle

For Fund I and II, the pitchbook is not primarily persuasion. It’s category education plus ownership of the angle.

You’re not trying to prove that you’re “better than” the usual suspects. You’re trying to:

- convince the LP that this slice of the world is worth allocating to, and

- convince them that you are the sharpest expression of that slice.

That’s a different mindset than the benchmark-heavy, context-heavy approach in a later-fund deck. LPs reviewing emerging managers are usually asking, “Do I believe this corner of the market deserves attention? And if I do, is this the right team to explore it?”

The deck has to make that pair of arguments cleanly.

Track Record Is Secondary to Strategy — Especially When You Can’t Own It

LPs don’t expect a pristine track record from a first-time fund. They do expect honesty and proportion.

Spinouts from larger firms are usually constrained: they can’t port formal attribution, they can’t present full performance histories as “theirs,” and they can’t pretend the prior platform didn’t matter. LPs know this. They’ve seen it a hundred times.

What LPs want in that scenario is not a tortured attempt to make the past do more work than it can. They want a crisp strategy and a handful of real examples that show how the manager thinks. The past is useful context — but only when it reinforces the forward-looking story.

If you can’t own the track record, you shouldn’t let the pitchbook behave as if you can. Credentialize, yes. Over-credentialize, no. LPs are far more interested in whether your angle is coherent than whether you can stack logos on a page.

LPs Expect the Deck to Make the Blind Pool Less Blind

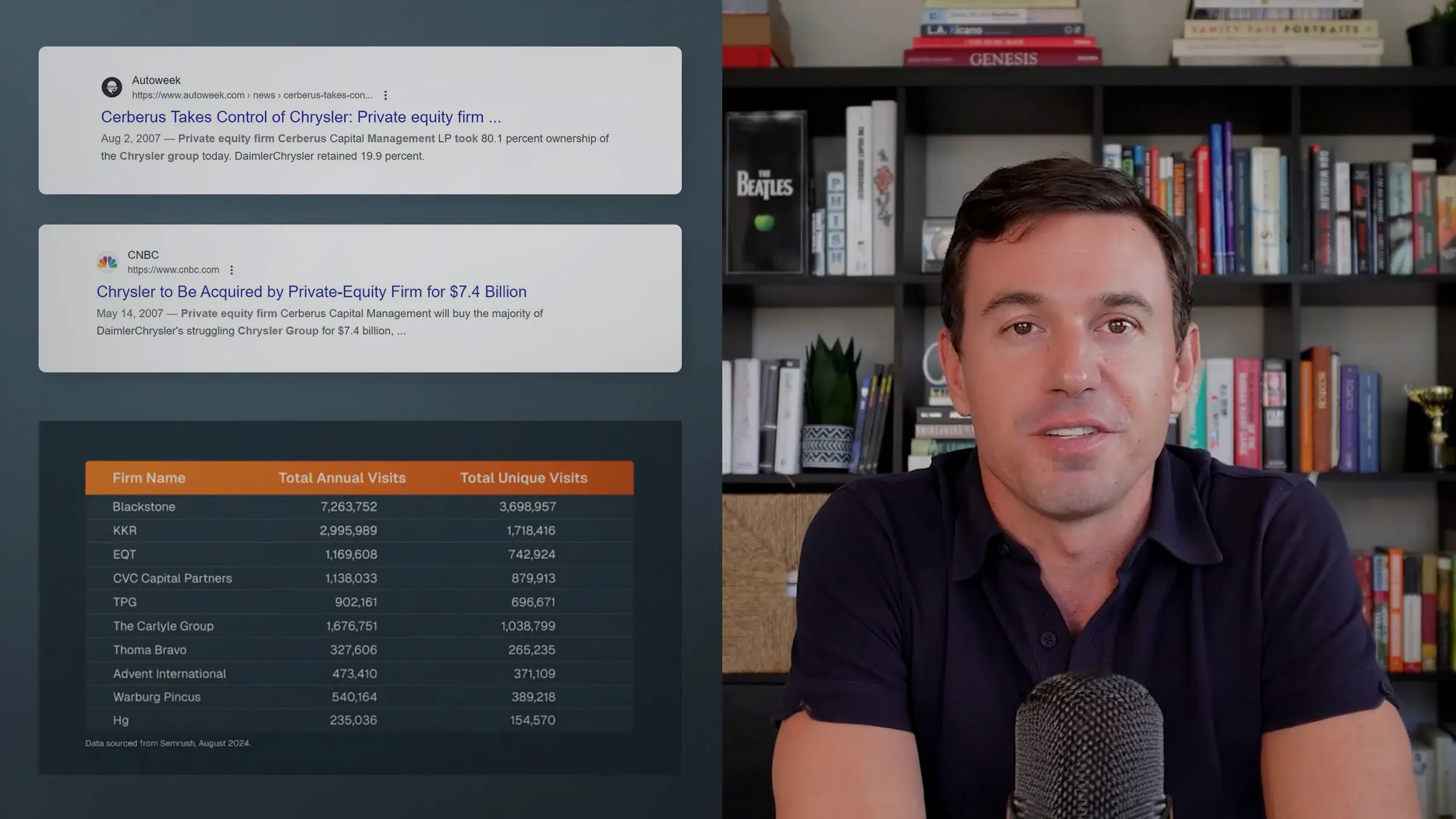

For managers who have done pre-fund or warehoused deals, the best Fund I decks use those deals to make the fund feel less hypothetical. BKM is a good example: six properties on balance sheet, financed by the founders, used not as “look how great we are” case studies, but as tangible evidence of what the fund will actually own.

LPs appreciate this not because they’re desperate for early marks, but because it gives them texture. It shows how the strategy behaves in the real world. The pitchbook stops being abstract. It becomes a guided tour of what the fund is likely to look like.

The same logic applies whether you’re doing real estate, private equity, credit, or some niche in between. Real deals make everything sharper — if they’re framed properly.

Closing Thought

LPs aren’t asking emerging managers for perfection. They’re asking for a few clear things: an understandable category, a believable angle, and a story that doesn’t sound like everyone else’s. The pitchbook is where those elements first come together — or fail to.

The biggest risk in a Fund I deck isn’t that you’ll use the wrong shade of blue or one too many charts. It’s that you will sound like yet another manager with a process, a funnel, and nothing memorable to say. LPs are not short on decks. They’re short on decks that feel like the first chapter of something they’ll be glad they backed in ten years.