.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Emerging managers tend to think of brand and design as a matter of taste — something that should look professional, aesthetically coherent, and aligned with the firm’s personality. LPs experience it differently. For them, brand and design are not an expression of style; they are a diagnostic. They offer clues about whether the GP is organized, disciplined, mature, and institutionally aware. Most emerging managers would never describe themselves as “inexperienced,” yet subtle design signals often convey precisely that impression.

The challenge is that LPs make these judgments unconsciously, and they make them early. Before you discuss the first deal example or outline the logic of your strategy, the LP has already formed a view about whether you are a serious institutional contender or an interesting emerging group still finding its footing. These judgments are not always fair, but they are remarkably consistent — and they shape everything that follows.

1. The Brand Reflects the Mind Behind It

One of the quiet truths in fundraising is that LPs project brand and design choices onto the investment process itself. A disorganized deck suggests disorganized underwriting. A cluttered website suggests cluttered thinking. An overdesigned visual system suggests a focus on performance rather than precision. No LP would articulate this directly, but years of pattern recognition have made them sensitive to the correlation between presentation quality and organizational maturity.

This is why emerging managers often underestimate the consequences of their design decisions. They assume LPs will look past the imperfections and “focus on the strategy.” LPs do the opposite. When the brand feels misaligned with the seriousness of institutional capital, they anchor on credibility gaps: Does the GP understand the level of professionalism expected? Will the firm mature fast enough to support a real fund? What else are they underestimating?

The brand is the first exposure LPs have to how you think. They use it to infer everything else.

2. Many Emerging Manager Brands Signal Something They Don’t Mean

In practice, emerging manager brands fall into a handful of avoidable traps:

The Developer Brand:

Website looks like it was built from a real estate developer’s template — busy, image-heavy, slogan-driven, and full of generic claims about “partnership” and “value creation.” LPs read this as lack of institutional awareness.

The Broker Brand:

Overly polished, promotional, and transactional in tone. LPs interpret this as an orientation toward deal-making rather than disciplined fund management.

The Startup Brand:

Trendy typography, clever taglines, or design choices more common in venture-backed tech than in institutional investment. LPs see this as misalignment with the culture of fiduciary responsibility.

The “Just a Logo and a PDF” Brand:

Spartan to a fault. An underpowered website paired with a pitchbook that feels like it was assembled for a bank lender, not an allocator. LPs read this as underdeveloped organizational maturity.

None of these signals are fatal, but they shape the LP’s cognitive frame before the GP speaks a single word.

3. Consistency Signals Maturity

Institutional investors expect consistency across brand touchpoints because it reflects operational discipline. A website that feels one way, a deck that feels another, and messaging that shifts depending on the audience signals instability. Emerging managers often dismiss this as a minor problem — something to “clean up later.” LPs don’t see it that way. They assume inconsistency in materials reflects inconsistency in underwriting, reporting, or strategy execution.

Brand consistency is not decorative; it is a proxy for organizational readiness. LPs don’t need you to be large, but they do need you to be coherent. A consistent brand signals the GP is capable of sustained, rigorous thought across multiple dimensions of the firm.

4. Design Maturity Does Not Mean Flash

Another mistake emerging managers make is assuming that a highly polished, visually dynamic brand will make them look more sophisticated. In reality, the opposite is often true. Institutional design maturity is quiet. It is subtle. It avoids unnecessary theatrics. LPs respond to restraint because it reflects seriousness of purpose — not a desire to impress.

The question LPs are evaluating is not “Does this look great?” but “Does this feel like the work of someone who knows what they’re doing?” When the visual system is too clever or too stylized, LPs read it as compensation. They assume the GP is trying to cover for something — usually a lack of track record or a strategy that has not been tightened enough.

The best emerging manager brands have a kind of intellectual modesty to them. They project confidence, not swagger.

5. LPs Default to “Risk Lens” When Evaluating Early-Stage Brands

Because emerging managers are inherently riskier than established platforms, LPs begin each interaction with an unspoken question: “Is this real?” Brand and design are the fastest way to answer that question, for better or worse.

When LPs see:

- a coherent narrative,

- a disciplined visual system,

- thoughtful materials, and

- mature design restraint,

they subconsciously shift into “evaluation mode” rather than “filtering mode.”

When they see:

- mismatched styles,

- inconsistent tone,

- decks that feel thrown together, or

- branding that feels aspirational rather than grounded,

they shift into “risk identification mode.”

These are not subtle distinctions. They meaningfully affect LP behavior.

Closing Thought

Brand and design are not the decoration around the strategy. They are part of the strategy’s credibility. Emerging managers misinterpret this not because they lack taste, but because they underestimate the extent to which LPs use presentation quality as a proxy for operational maturity. The visual system around a Fund I or Fund II strategy sends dozens of signals in seconds — about discipline, seriousness, category fluency, and whether the GP understands institutional expectations.

In a world where LPs filter quickly and remember little, the brand becomes the scaffolding that makes the rest of the story believable. It is not peripheral. It is foundational.

Investor communication in real estate used to follow a predictable pattern. Closed-end funds ran annual meetings or semi-annual update calls with institutional LPs. Non-traded REITs delivered periodic webinars and mailed highly structured update packets. Advisor-distributed products issued their required reporting and hosted occasional introductions. Family-office vehicles communicated however the family wanted to communicate.

Today, those lines are blurred.

Every vehicle type now operates under heightened expectations.

Institutions expect clarity and brevity.

Family offices expect candor.

Advisors expect digestibility.

High-net-worth investors expect reassurance.

And all of them expect the manager to communicate cleanly, confidently, and without overwhelming them.

Against this backdrop, the investor presentation — whether delivered live, via webinar, or as an asynchronous deck — is no longer a box-checking ritual. It’s a primary storytelling moment. It’s one of the few chances a manager has to shape how investors understand the portfolio, the strategy, and the environment in which both are operating.

The challenge is that most real estate teams approach these presentations the way they approach their day-to-day: with detail first and structure second. But investors don’t absorb information that way, especially across formats. The more cyclical, complex, and multi-audience the real estate world becomes, the more a presentation must be engineered — not just assembled.

1. Every Vehicle Has a Presentation Format, Even If It Doesn’t Call It an “AGM”

Closed-end funds hold annual or semi-annual meetings, and these feel familiar to most managers. But nearly every other structure has its own equivalent:

- Non-traded REITs run quarterly investor webinars.

- Interval funds publish and present NAV commentary.

- 1031/721 platforms provide deal-by-deal property updates.

- Advisor-distributed products hold virtual education sessions.

- Family-office partnerships request periodic portfolio deep dives.

- Open-end funds host rolling update calls as conditions change.

The names differ.

The audiences differ.

The regulatory wrappers differ.

But the core purpose is identical:

orient the investor, contextualize the portfolio, and reaffirm the competence of the platform.

Investors are not waiting for a performance surprise; they’re waiting for narrative clarity.

2. Most Managers Overestimate What Investors Want to Hear and Underestimate How They Process Information

Real estate teams tend to live deeply inside their own operational details. They know every acquisition, every lease-up, every disposition, every property-level story. They know the underwriting nuance and the debt structure and the submarket dynamics. When preparing investor materials, it’s tempting to bring all of that detail into the presentation.

But investors — regardless of sophistication — do not process detail until they understand the frame. A strong investor presentation provides that frame quickly.

The structure rarely changes:

- Where are we in the cycle?

A calm, specific, non-alarmist explanation of the market environment. - How does that environment intersect with our strategy?

The update is more compelling when the strategy feels responsive to conditions. - What do we want investors to understand about the portfolio right now?

Not everything — just the essentials that illuminate the story. - Where is the team focused next?

Investors want orientation, not prediction.

Only after those pieces are established does property-level or segment-level detail become meaningful. Without that frame, the presentation becomes a tour of unrelated slides rather than a coherent briefing.

3. Webinars Are Their Own Medium — and They Expose Weakness Quickly

Many real estate managers deliver their most important presentations via webinar, especially in the REIT, interval, and wealth-channel segments. But webinars are unforgiving. Attention drops faster. Visual clutter becomes more noticeable. Dense slides feel heavier. The presenter’s pacing has an outsized effect on comprehension.

The constraints make clarity non-negotiable.

Slides must be cleaner.

Narratives must be tighter.

Photography must serve a purpose.

Exhibits must be readable on a laptop screen.

And the story must unfold in a sequence that feels almost inevitable.

A good webinar slide is not a meeting slide.

A good webinar slide is simpler, sharper, and more deliberate.

Done well, webinars can deepen connection with audiences who may never meet the manager in person. Done poorly, they highlight every weakness in the deck — and often every weakness in the presenter’s preparation.

4. Advisor and RIA Audiences Require a Different Sensibility

The advisor and wealth channels bring their own dynamics. Advisors are intermediaries; they must digest your story and pass it along. They cannot do that if the materials are too dense or too technical. They must be able to explain what the vehicle does in one or two sentences. They must be able to answer their clients’ surface-level questions without returning to the manager every time.

This means investor presentations for advisor-distributed products cannot simply be simplified versions of institutional decks. They require their own design logic:

- fewer slides,

- fewer exhibits,

- clearer language,

- more narrative support,

- direct framing of “what this means for investors,”

- and visuals that can scale down into 4-pagers, landing pages, or email follow-ups.

Many managers underestimate how much of their capital formation success — or failure — comes down to whether advisors feel equipped to retell the story.

5. Consistency Across Presentations Builds Credibility Over Time

Whether the format is a webinar, a live presentation, or an asynchronous deck, investors track one thing above all else: consistency. They notice when the quarterly update matches the voice of the pitchbook. They notice when the portfolio overview feels synchronized across platforms. They notice when each presentation seems to pick up the narrative where the last one left off.

On the other hand, when materials look or sound different every quarter — different fonts, different structures, different design rules, different tones — investors feel the discontinuity. They wonder whether the team is stretched or whether responsibilities are unclear internally. Consistency doesn’t just make the materials easier to read; it makes the organization feel more intentional.

Narrative coherence over time is one of the strongest trust signals an investment manager can send — especially in a category as cyclical and sentiment-driven as real estate.

6. Where DG Supports the Presentation Layer

For many clients, investor presentations are the single place where capability gaps strain the organization. Teams may not have the bandwidth to prepare for webinars. They may not have design support for producing clean decks in PowerPoint. They may struggle to translate operational detail into investor-friendly narrative. They may need a neutral party to help them decide what to include — and what to leave out.

DG steps into that gap:

refining the story, sharpening the structure, upgrading the visuals, standardizing the design system, preparing templates, supporting scripts or speaking notes, and ensuring the materials feel aligned with the firm’s broader brand and strategy. For many clients, DG becomes the continuity across multiple formats, multiple audiences, and multiple vehicle types.

When the presentation layer is strong, capital formation feels easier — because investors feel continuously oriented, not periodically reintroduced.

Closing Thought

Investor presentations are no longer occasional events. They are recurring opportunities to reinforce confidence, renew clarity, and show investors that the manager is disciplined not just in the way they invest, but in the way they communicate. Whether delivered in a meeting room, over a webinar, or through an advisor-education session, the mechanics differ but the principle is the same:

a good presentation reduces friction and increases trust.

Real estate managers who approach these moments with intentionality — and who treat communication as a year-round discipline — put themselves in a far stronger position when the next phase of capital formation begins.

Emerging managers tend to imagine LPs evaluating them in a formal setting: the meeting room, the pitchbook walkthrough, the diligence call. But in Fund I fundraising, the most consequential judgments often form before any of that happens — and they’re formed through small digital behaviors the GP barely registers. LPs read these signals the way a seasoned casting director reads posture or tone before an actor delivers a single line. It’s not the main evaluation; it’s the pre-screen.

Digital presence is not just a website. It is a trail of micro-signals — LinkedIn profiles, signatures, bios, email tone, file naming conventions, the structure of a data room, the way materials are shared — that collectively tell LPs whether a GP is ready for institutional capital or is still assembling the scaffolding of a real firm. These signals matter because they offer a glimpse into how the GP will behave when the stakes are higher and the details are messier.

Emerging managers underestimate these signals not because they’re careless, but because they simply haven’t been trained to see what LPs see.

1. Digital Identity Is the First Test of Whether a Firm Is “Real”

LPs begin evaluating you the moment they search your name. Before they know the strategy, before they meet the team, before they read the deck, they are forming a simple judgment: Does this firm actually exist in the institutional sense of the word?

New managers sometimes forget that they are asking LPs to take a leap of faith. There is no long track record, no deep bench of partners, no decades-old brand. LPs need signals that you are building an actual firm — not testing the water, not “seeing how Fund I goes,” but constructing something that will exist in year five and year ten.

Digital presence becomes the earliest proof-of-intent.

If the signals are faint or inconsistent, LPs assume the intent is faint or inconsistent too.

2. LPs Notice Whether the Firm Has Claimed Its Digital Territory

Something as simple as:

- an unclaimed Google Business listing,

- LinkedIn profiles with placeholder language,

- outdated bios,

- or inconsistent job titles

causes LPs to pause — not because they’re judging the brand, but because they’re assessing the organizing competence behind the brand.

Institutional allocators view a digital footprint the way a botanist views root structure. They assume what’s visible is an indicator of what’s invisible. If the visible infrastructure is thin or chaotic, they infer the same about everything else.

3. Tone Is a Digital Behavior, and LPs Hear It Clearly

Tone is one of the most subtle digital cues, and one of the most consequential. LPs pick up emotional data from:

- the firmness or softness of your language

- how you describe your category

- whether your voice sounds confident or apologetic

- whether your tone is stable across mediums

- how your emails read — composed? hurried? overly promotional? underthought?

Tone inconsistencies cause LPs to ask whether the GP has fully formed their worldview. If the voice on the website doesn’t match the voice in the deck — or the voice in the deck doesn’t match the voice in the email — LPs notice instantly. They may not know what’s wrong, but they can feel the mismatch.

For emerging managers, tone is the first “vibe check,” and LPs trust their instincts.

4. Digital Organization Reveals Operational Discipline

LPs are forever trying to separate signal from noise. They know every GP can say the right things. What they’re looking for are signs of how the GP actually works — how they handle process, structure, detail, and follow-through.

Digital organization becomes a proxy:

- a clean, well-labeled data room

- logically named files

- a deck that feels intentionally sequenced

- bios that share a common tone

- a website that reinforces, rather than contradicts, the pitch

These are not compliance checks. They are cognitive shortcuts. LPs assume that a GP who cannot create digital order may struggle to create operational order. And while the correlation isn’t perfect, it’s reliable enough that LPs have learned to trust it.

5. LPs Experience Consistency as Maturity

One of the most underrated digital signals is consistency — not great design, not prolific content, not SEO dominance, but simple, calm consistency across all touchpoints. Even a modest digital presence, when coherent, signals that the GP is ready for institutional conversation.

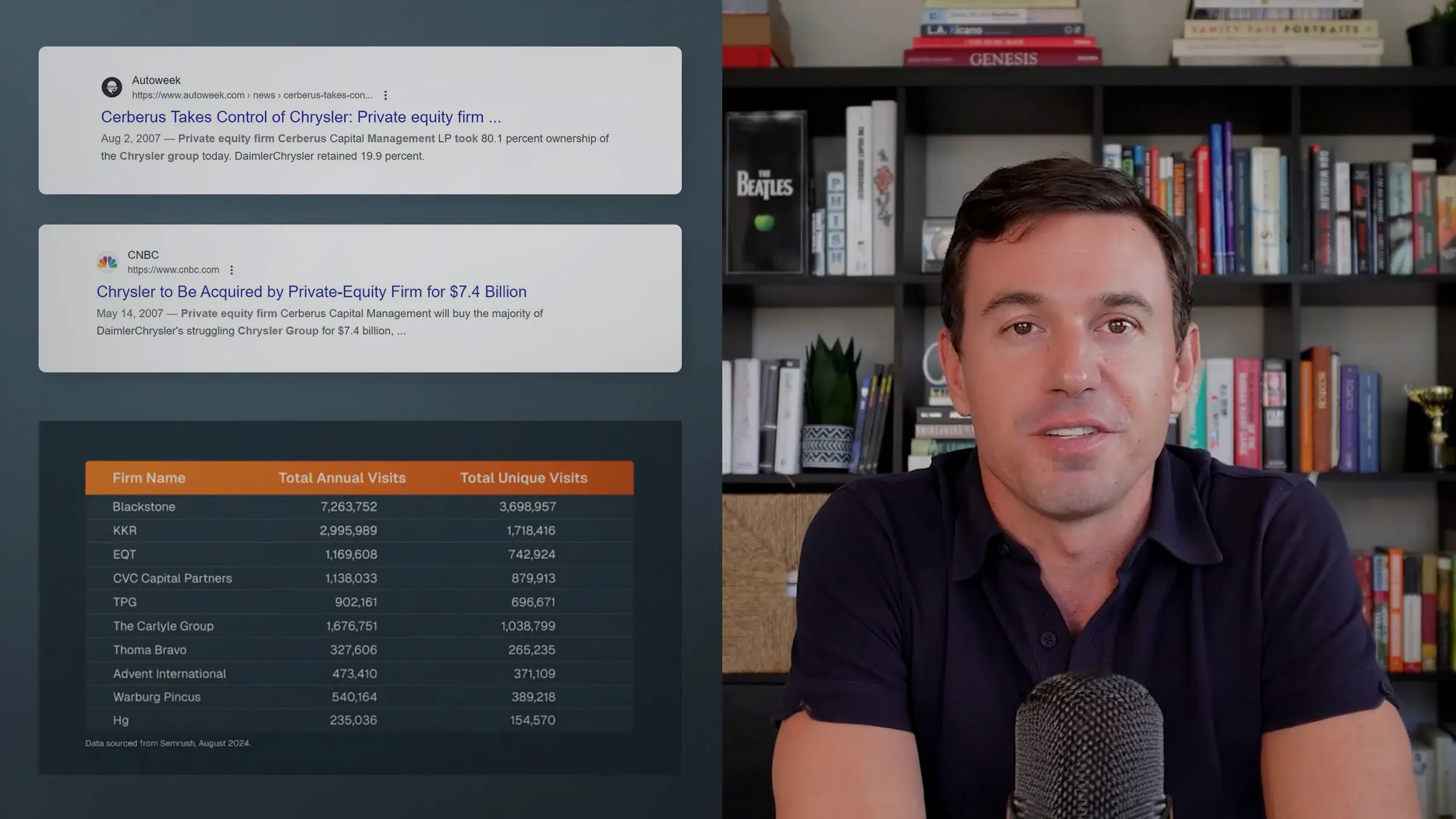

Emerging managers underestimate how rare digital consistency is. They imagine LPs comparing them to Blackstone or Carlyle. LPs aren’t doing that. They’re comparing them to the dozens of emerging managers who present different versions of themselves across their materials.

Inconsistency reads as drift.

Consistency reads as maturity.

And in Fund I fundraising, maturity is scarce enough to be a differentiator.

6. Content Behaves Like a Digital Signature, Not a Marketing Tactic

Emerging managers often ask whether they “need” content. LPs are not looking for volume. They are looking for evidence that the GP has a point of view — an internal logic strong enough to produce even one or two pieces of thoughtful writing or video.

A small amount of meaningful content signals:

- the GP understands their category,

- they have something to say about it,

- they are confident enough to put those ideas into the world,

- and they intend to be part of the category’s intellectual future.

Content is a way of saying, “We’re not experimenting; we’re committing.”

And in the coming LLM-driven world — where allocators will increasingly ask intelligent systems for recommendations in niche categories — content becomes not just a credibility asset, but a discoverability asset.

Closing Thought

Digital behavior is not decoration. It is the earliest expression of how a GP thinks and how a firm operates. LPs are constantly scanning for signs of maturity, coherence, and intention, and they make these judgments long before the first meeting. Emerging managers who treat digital presence as part of their strategy — not an afterthought to it — close the legitimacy gap faster and create more chances for serendipity.

Fundraising isn’t just about the pitch. It’s about the pre-pitch.

And in that world, digital behavior often speaks first.

Real estate reporting occupies an unusual place in the investment communications landscape. In many structures — non-traded REITs, interval funds, 1031/721 platforms, and certain private vehicles — the legally required reporting is extensive, structured, and tightly governed. Audited statements, compliance-driven updates, NAV disclosures, distribution notices, and required quarterly or annual filings create a baseline rhythm that every manager must follow.

Because of this, managers often assume that “reporting” is largely a compliance exercise. The logic is understandable: if the law already dictates much of what investors must receive, then the communication burden is largely solved. But in practice, the legal layer is only the foundation. The reporting that actually shapes investor confidence—and differentiates one manager from another — lives above the required disclosures.

Investors don’t just want information; they want comprehension. They want clarity, rhythm, and narrative coherence. They want to understand how to interpret what they’re seeing. And they want to feel that the manager is communicating with intention rather than simply meeting an obligation.

This is where reporting becomes a brand advantage rather than a regulatory task.

1. Compliance Reporting Is the Floor, Not the Ceiling

Required filings — financial statements, mandated disclosures, NAV updates, distribution notices — are essential, but they are not designed to help investors understand the story. They are meant to be complete, accurate, and compliant. They are not meant to be persuasive or intuitive.

An institutional LP may be accustomed to deciphering complex statements. A family office CIO may have the pattern recognition to contextualize the numbers quickly. But advisors, RIAs, and high-net-worth investors often need interpretation, not just data. They want to know what the data means in the context of the strategy, the cycle, and the manager’s decisions.

When that layer is missing, reporting feels mechanical and opaque — even if the underlying performance is strong.

The difference between a manager who “checks the box” and one who builds trust is often found in the communication that accompanies the required filings.

2. Investors Respond to Reporting That Explains, Not Just Informs

Real estate is tangible, but real estate reporting often isn’t. Investors receive numbers, tables, and property-level information that doesn’t always translate cleanly into investor-level insight.

What investors want, regardless of sophistication, is orientation:

- What’s happening?

- Why is it happening?

- How should I interpret this?

- Where is the manager focused?

- What’s coming next?

Strong reporting bridges the gap between operational detail and investor comprehension. A quarterly letter or supplemental update doesn’t need to be long. In fact, brevity and clarity are usually more persuasive. But it does need to frame the numbers in a way that helps investors understand the arc of the strategy.

This interpretive layer is where reporting becomes a strategic communication tool rather than a compliance exercise.

3. Consistency Builds More Trust Than Volume

Investors across all channels — institutions, family offices, advisors, RIAs, and individuals — respond strongly to rhythm. When communication appears predictably, with a consistent structure and voice, investors stop wondering whether something is wrong. They begin to experience the manager as steady, attentive, and organized.

Inconsistent reporting, on the other hand, creates unnecessary shadows. Investors don’t assume disaster, but they do assume disorganization. They wonder whether the manager is understaffed, distracted, or stretched. They begin to question whether the team is too thin to manage both investments and investor relations.

Consistency is not about sending more. It’s about creating an expectation and meeting it.

A quarterly letter should feel like part of a series.

A supplemental update should feel like an extension of the brand.

New acquisition or disposition notes should feel like they come from the same organization that produced the pitchbook.

This coherence has a compounding effect. When the next capital formation moment arrives, investors already trust the manager’s communication discipline.

4. Reporting Quality Is a Direct Reflection of the Manager’s Brand

Managers sometimes think of reporting as an operational necessity rather than a brand expression. But for most investors, especially those outside the institutional core, reporting is the primary way they “experience” the firm.

If the pitchbook or website sets the initial impression, reporting sustains it. It reinforces the firm’s identity and signals whether the manager is still aligned with the story that first attracted the investor. Clean, modern, well-organized updates signal a level of attentiveness that carries through to the portfolio.

Conversely, poor reporting — dated formatting, inconsistent charts, overly dense paragraphs, mismatched visuals — suggests something deeper. Investors subconsciously link communication quality to operational discipline. If the materials feel sloppy, they wonder what else might be sloppy. That reaction isn’t always fair, but it is predictable.

Reporting is one of the most powerful brand builders a real estate manager has. Most don’t treat it that way.

5. Different Investors Need Different Levels of Interpretation

One of the challenges (and opportunities) in real estate reporting is the diversity of investor audiences. Institutions, family offices, RIAs, and individuals interpret the same information differently.

Institutions tend to be analytical and process-driven. They want clarity but can handle detail. Family offices vary widely — some are highly sophisticated, others more instinctual — but all tend to appreciate directness. Advisors and RIAs need materials that are digestible enough to pass along to clients. High-net-worth individuals interpret information more emotionally, often responding more to the story than the mechanics.

A well-constructed reporting package can speak to all four groups without diluting its message. The key is making the structure intuitive: clear headlines, concise narratives, well-organized exhibits, and a steady voice.

Everyone reads for clarity. Few have patience for clutter.

6. Where DG Adds the Most Value

Most real estate teams are not built to produce institutional-quality reporting in-house — and they shouldn’t be. Their core expertise is investing, not communication. Reporting becomes a bottleneck because it requires writing, design, narrative judgment, and production discipline — all skills that tend not to be concentrated on an investment team.

DG’s support solves that bandwidth and capability gap. We help clients:

- modernize their reporting templates;

- translate operational detail into investor-accessible language;

- ensure that recurring documents match the brand and the website;

- produce clean charts and exhibits that don’t feel repurposed or mismatched;

- maintain consistency across quarters and across vehicles;

- create reporting that feels like an extension of the pitchbook (not a separate universe).

And — perhaps most importantly — we help managers communicate proactively during cycle shifts, market volatility, or periods of operational complexity.

Reporting does not have to be ornate. It has to be clear, coherent, and consistently executed. That alone separates a manager from the pack.

Closing Thought

Required filings satisfy the rules.

Thoughtful reporting satisfies the investors.

The managers who build trust over the long term understand the difference. They know that reporting is not just informational—it’s interpretive. It’s the way investors experience the discipline, maturity, and attentiveness of the platform.

Real estate managers who treat reporting as a brand-strengthening activity — not just a compliance obligation — find that future capital conversations begin on much firmer ground. Communication doesn’t raise capital by itself, but it builds the confidence that makes capital formation easier.

When emerging managers think about web design, they think about aesthetics — colors, typography, layout, the overall “look” of the site. LPs experience something else entirely. To them, design is a diagnostic. It reveals how a manager thinks, how they make decisions, and whether they understand the expectations of the institutional world they’re trying to enter. A Fund I website might be your smallest asset in terms of size. But in terms of signal? It’s enormous.

Design is not telling LPs whether you’re creative or polished. It’s telling them whether you’re ready.

1. LPs Read Design as Organizational X-Ray

When an LP looks at a website, they’re not evaluating the visuals. They’re evaluating what the visuals imply.

They ask themselves:

- Does this firm think clearly?

- Does this feel like a real organization — or like the beginning of one?

- Does the design match the seriousness of the strategy?

- Did someone make intentional decisions here, or did the GP hand the work to whoever could get it done quickly?

Design becomes a proxy for operational discipline. A coherent website suggests that the manager has the same coherence in underwriting, communication, and internal process. A sloppy or mismatched site suggests the opposite.

It’s unfair at times, but it’s reliable. LPs have learned that good design correlates with good decision-making more often than not.

2. Restraint Is More Persuasive Than Ornamentation

Emerging managers often think their design needs to impress — especially when they’re competing against established platforms. They assume more will help: more visual flair, more motion, more cleverness. But LPs respond to something quieter.

Institutional design maturity looks like:

- focus

- clarity

- intentional spacing

- elegant typography

- a restrained visual system

Restraint signals confidence. It says, “We’re not compensating for anything. Our story is strong enough to stand in clean air.”

Design that tries too hard sends the opposite message. Emerging managers sometimes adopt startup-like aesthetics to appear modern, but LPs interpret that as immaturity. Conversely, adopting the stiff, conservative style of a 40-year-old Park Avenue firm suppresses the newness that makes emerging managers interesting in the first place.

The sweet spot is modernity with discipline — a visual identity that feels sharp, young, and serious at the same time.

3. Emerging Managers Should Look Like Emerging Managers (Not Miniature Incumbents)

There is a certain kind of visual timidity that creeps into emerging manager branding. The GP doesn’t want to look inexperienced, so they adopt a visual language that’s indistinguishable from established funds: corporate blues, symmetrical grids, conservative typography. Everything looks “fine,” but nothing looks like the beginning of something new.

This is a mistake.

One of the natural advantages emerging managers have is precisely what older firms can never get back: newness. LPs don’t want you to look like a 30-year-old firm. They want you to look like the future of a 30-year-old firm. They want to believe they are seeing the debut of someone who sees the category more sharply than the incumbents do.

In arts terms: the exciting new director is rarely the one who mimics the old masters. They’re the one whose first film has a distinct visual world — focused, disciplined, unmistakably theirs.

A digital identity that leans into that energy signals ambition, clarity, and the possibility of scale.

4. Consistency Across Digital Touchpoints Signals Alignment

LPs cross-reference everything:

- website

- deck

- bios

- email tone

- data room structure

When these elements feel unified, LPs infer that the manager knows who they are. When they feel mismatched, LPs infer that the story is still forming.

A mismatch between the deck and website is particularly damaging. LPs don’t know which version to believe. If your language evolves, your digital presence must evolve alongside it. Emerging managers underestimate how instantly LPs notice these fractures.

Narrative consistency begins digitally. If you don’t show alignment in your materials, LPs assume they’ll have to find it in your underwriting — and that’s a risk they’d rather not take.

5. Why Cheap Early Websites Send the Wrong Signal

(This is the second and last post where this argument appears.)

New managers often start with a low-cost site — Squarespace, a freelancer, or someone a friend recommended. You can make this work, but you probably won’t get what you need.

Here’s the deeper reason:

A cheap site signals that the GP has deferred the hard thinking about who they are.

And that is exactly the thinking LPs want you to have done.

Cheap early sites introduce three quiet liabilities:

- They look like placeholders.

LPs see that instantly. It tells them your identity is still in draft form. - They force generic language.

Templates flatten nuance. They make you sound like everyone else. - They cost you impressions during the most impression-sensitive period of your firm’s life.

Fund I is full of consequential first encounters:

one seller, one placement agent, one CIO who happens to click at the right moment.

Every B-minus impression is a lost probability.

And just as important: cheap sites force founders to spend their time babysitting the process — something no Fund I GP has time for. Your time is your scarcest resource. You can’t spend it correcting someone who doesn’t understand your business.

Closing Thought

Design is not window dressing. For emerging managers, it is one of the few tools available to close the legitimacy gap quickly. LPs aren’t looking for flash. They’re looking for intention. They’re looking for signs that the GP is building something that will still make sense in ten years. A disciplined digital identity does that. A lazy one does the opposite.

The firms that break through aren’t the ones trying to look bigger than they are. They’re the ones who look exactly like what they are: a sharp, new manager with a point of view strong enough to grow into an institution.

One of the quiet realities of emerging manager fundraising is that most firms, despite sincere effort and real expertise, end up sounding nearly identical to one another. The strategies vary at the margins, but the language rarely does. LPs hear about disciplined underwriting, proprietary sourcing, operational value creation, conservative leverage, and “alignment” so frequently that these terms have lost all power as differentiators. Everyone is disciplined. Everyone has a network. Everyone claims an edge.

The problem isn’t dishonesty. The problem is structural. Emerging managers are trying to articulate sophisticated ideas in a crowded market where LPs are listening through mental models built over decades. When your audience has been exposed to hundreds of similar pitches, differentiation becomes less a matter of originality and more a matter of precision — the ability to define the specific angle you have on a category, and to communicate it in a way that actually survives the LP’s internal filter.

Differentiation for emerging managers is rarely about inventing something new. It is about identifying what is uniquely durable in your view of the world and expressing it with enough clarity that an LP could repeat it accurately later. Most emerging managers fail here not because they misunderstand their strategy, but because they have never been forced to distill the one or two ideas that actually set them apart.

1. The Category Problem: LPs Don’t Hear the Sharp Edges

LPs begin by sorting managers into categories. They are trying to understand whether they’ve heard this story before, where it fits inside their allocation framework, and whether your variation on the theme has any real structural advantage. If you cannot state the category clearly, LPs will assign you one — and usually not the one you prefer.

This is why emerging managers often sound indistinguishable. They are describing their strategy in terms of activities (“We source proprietary deals”) instead of positioning within the category (“We capture forced-seller dynamics in micro-cap carve-outs that are too operationally messy for mid-market funds”). The first is noise. The second is narrative.

When I ask emerging managers what makes their strategy distinct, many give me a list of traits rather than a point of view. Traits blur together. Points of view stand out. LPs aren’t looking for novelty; they are looking for a worldview they can evaluate.

2. The Overstuffing Trap

Another reason emerging managers sound the same is because they try to include everything — every sourcing channel, every operating lever, every historical observation about the market. In an attempt to appear comprehensive, they dilute exactly the things that make them distinctive.

I’ve seen pitchbooks with five different “value creation strategies,” eight elements of “differentiation,” and entire paragraphs dedicated to generic industry dynamics. None of this is harmful on its own, but it accumulates into something LPs experience as fog. The sharper points get buried. The nuances flatten into cliché.

Differentiation is the art of exclusion. You cannot be known for eight things. You can barely be known for three. The emerging managers who break through are those who have the discipline to foreground what matters and let the rest function as supporting evidence rather than the headline.

3. Specialization Is a Differentiator — But Only If You Own It

Specialization is the closest thing the emerging manager universe has to a cheat code. When a strategy is tightly defined, LPs can evaluate it more easily. It signals coherence, clarity, and conviction — three qualities LPs associate with institutional readiness.

But specialization only works when the manager owns it fully. Too often, emerging managers retreat from specialization at the exact moment it could help them. They worry the category is too narrow, or too fringe, or too underappreciated to be fundable. They broaden the language to “hedge” against LP skepticism, and in doing so, they give up the very thing that could differentiate them.

When BKM launched Fund I in 2014, multitenant industrial was not a category LPs understood. It was considered “too messy” and “too operational.” The way we broke through was not by softening the specificity but by sharpening it. We educated the market. We stayed consistent. We owned the category fully. What was initially perceived as a disadvantage became a structural edge because the story was told with conviction.

Emerging managers often underestimate how much LPs appreciate a manager who can articulate a category with unusual clarity. It suggests the GP has done the thinking required to operate in it.

4. The Real Threat to Differentiation: Generic Strategy Language

The biggest threat to differentiation is not competition; it is internal vagueness. When a manager cannot identify the core drivers of their strategy, the deck becomes a collage of generalized statements. That creates an unintended signal: if the GP cannot express their own edge clearly, the LP assumes the edge may not exist.

Good differentiation is not a list of features. It is a logic chain — an explanation of why a specific set of conditions in a category produces mispricing or opportunity, why the manager is structurally advantaged to capture it, and why that advantage is durable. Emerging managers who articulate this chain well often outperform more experienced peers in early fundraising conversations because the story feels cleaner and more investable.

5. Why Differentiation Matters More Than Ever

The bar for emerging managers has risen. LPs filter faster. They have more options. They can only add a handful of new relationships in any given cycle. In this environment, differentiation is not a marketing exercise — it is the mechanism by which an LP decides whether to spend time on you at all.

Strong differentiation signals:

- that the manager knows exactly who they are

- that the strategy is coherent

- that the edge is real

- that the GP has thought deeply about category structure

- that the firm is institutionally ready

Emerging managers who skip this work end up competing on charisma or vague claims of “superior deal flow.” Those who embrace it position themselves as the sharpest expression of an idea.

Closing Thought

Differentiation is often treated as a cosmetic exercise, but in emerging manager fundraising, it is foundational. LPs do not choose the most charismatic manager or the most complex strategy; they choose the one whose worldview is easiest to understand and hardest to confuse with anyone else’s. When you claim less and clarify more, your story travels further. And in a world where LPs hear hundreds of pitches a year, the story that travels is the story that wins.