.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Capital formation in real estate is not a single moment. It is not a three-month sprint every few years, nor is it defined solely by the launch of a new fund or a push toward a specific raise target. Real estate managers today operate across a spectrum of structures — closed-end funds, non-traded REITs, interval funds, 1031/721 exchange platforms, private credit hybrids, and family-office vehicles — that all require communication before, during, and after the formal act of raising money.

Each structure comes with its own cadence. A non-traded REIT may run quarterly webinars and distribute monthly updates. A closed-end fund may go quiet for long stretches, punctuated by fundraising windows or major portfolio milestones. An interval fund has a predictable NAV cycle. A 1031 platform has deal-by-deal execution requirements and time-sensitive messaging. And a family-office vehicle may require bespoke, highly personal communication across several stakeholders.

The constant across all of these is the need for clarity, consistency, and clean execution — especially in the periods where capital formation is not at the forefront. Those “between” periods often determine how smoothly the next capital moment unfolds.

This is where real estate managers tend to underestimate both the volume and the importance of communication. And it is where DG does the most meaningful work.

1. Capital Formation Is a Continuum, Not an Event

Real estate managers often think of capital formation as something that happens “when we’re raising.” In practice, capital formation begins long before the first investor conversation and continues long after the final close — or, in the case of evergreen and retail-distributed vehicles, continues indefinitely.

Every communication touchpoint influences how investors experience the manager:

quarterly updates, distribution announcements, market commentary, acquisition notes, disposition highlights, share-class updates, property-level snapshots, new team hires, refreshed website content, and even small design decisions around recurring documents.

None of these individually raise capital. Collectively, they shape the investor’s perception of maturity, discipline, and preparedness. And when the next capital moment does arrive, managers who have communicated consistently throughout the cycle find that the raise itself is far smoother. Investors have already been oriented; trust has already been reinforced.

Capital formation is not episodic. It is environmental.

2. Why Communication Quality Matters Between Capital Moments

The periods between capital formation phases reveal more about a manager than the phases themselves. During an active raise — or a product launch — most firms are on their best behavior. Materials are polished, messaging is rehearsed, and deadlines are clear. But investors also evaluate what happens when things are quieter.

Institutions want to see narrative discipline across time.

Family offices want directness and clarity.

Advisors and RIAs want digestibility.

High-net-worth investors want confidence.

Retail channels want transparency and cadence.

None of these audiences assumes perfection. But each responds strongly to a manager who treats communication not as a transactional obligation, but as an ongoing expression of how the firm thinks and operates.

This is where the principles from the pitchbook work — clarity, skimmability, sequencing, coherence — carry forward. The same attention to structure that strengthens a fundraising deck strengthens an investor update. The same design discipline that makes a pitchbook feel institutional makes a new-acquisition announcement feel mature. The same narrative restraint that keeps a market section from ballooning into 20 slides keeps a quarterly letter readable.

The mechanics differ by audience and vehicle type.

The underlying expectation does not: communicate well, and communicate consistently.

3. The Communication Burden Most Managers Underestimate

What most real estate teams do not fully account for is the variety of communication types they must produce, even when no raise is in progress.

That burden includes:

- periodic fund or vehicle updates that explain performance in accessible language;

- property-level communication that translates operational detail into investor-relevant terms;

- portfolio-level storytelling that connects individual deals to the strategy;

- new acquisition or disposition announcements that maintain momentum and visibility;

- macro or cycle commentary when investors need context;

- distribution or NAV updates in REIT or interval-fund structures;

- updates to pitchbooks, factsheets, or 4-pagers as conditions evolve;

- website enhancements that reflect the current state of the firm;

- materials for advisor-education or family-office introductions;

- support for webinars and investor calls;

- and the ongoing expectation that documents look modern, aligned, and consistent.

This is not about volume for its own sake. It is about the reality that most management teams simply do not have in-house capability across writing, design, presentation development, website upkeep, and narrative framing. The CFO, CIO, or COO often ends up doing work that would be better performed by communications professionals — and even then, the output varies because no one has time to maintain rigor across dozens of touchpoints.

This isn’t a flaw in the organization. It’s a structural mismatch between what real estate teams are built to do (invest) and what the modern capital environment increasingly demands (communicate).

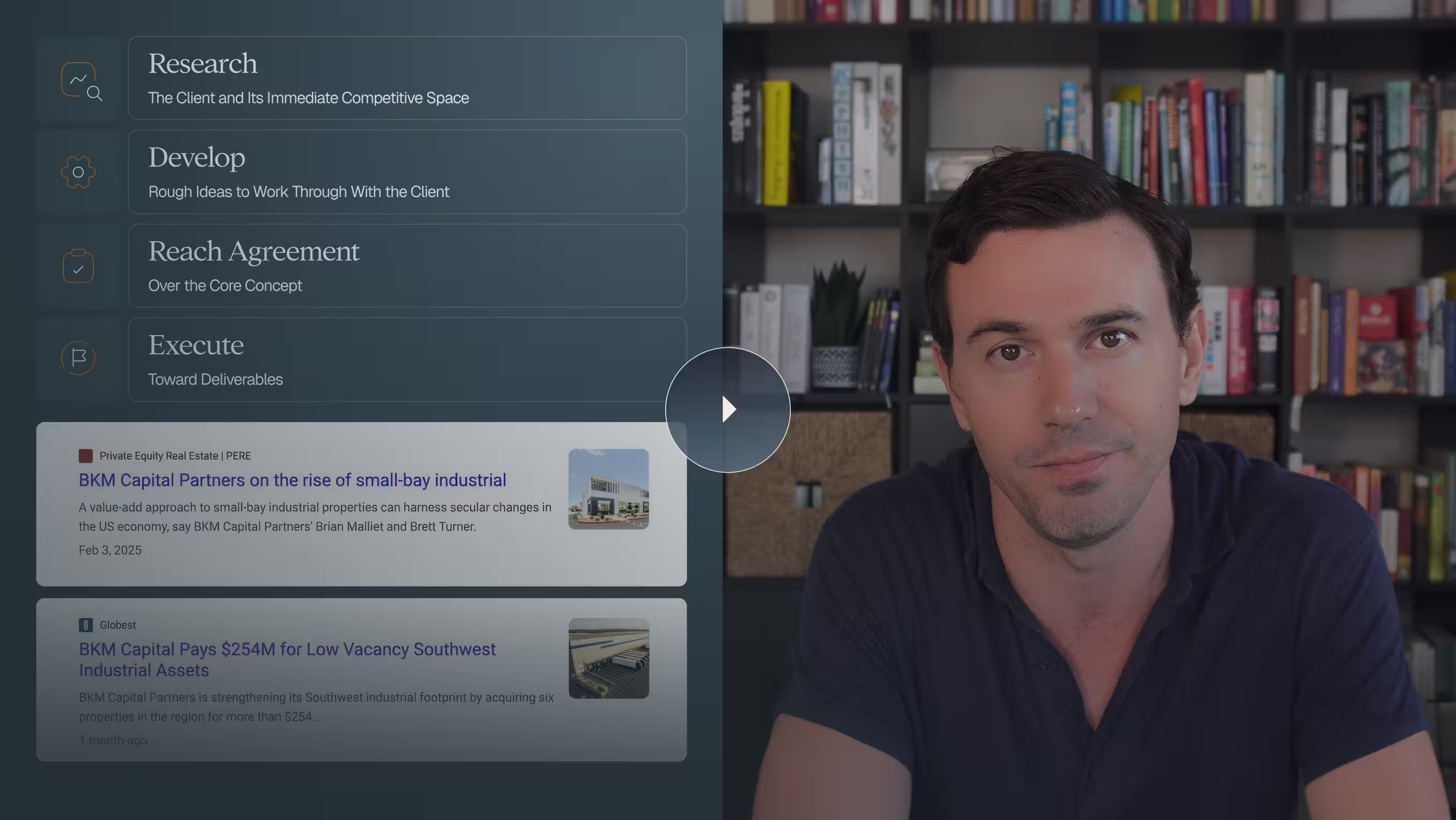

4. DG’s Role Across All Phases of Capital Formation

DG’s support is not a substitute for an internal team. It is a complement — a way to ensure that communication remains clean, consistent, and strategically aligned even when internal bandwidth is constrained.

That work includes:

- maintaining narrative clarity as markets shift;

- refreshing pitchbooks, factsheets, 4-pagers, and advisor decks;

- producing investor updates that are digestible, modern, and audience-appropriate;

- transforming operational detail into investor-ready communication;

- designing and supporting investor webinars across REIT, interval, and fund structures;

- organizing content so the story remains consistent across dozens of deliverables;

- updating websites whenever the portfolio, team, or strategy evolves;

- supporting deal or disposition announcements;

- creating marketing calendars for teams who have never operated on one;

- and acting as on-demand design and communications capacity whenever teams hit a bottleneck.

For many clients, DG effectively becomes the “communications infrastructure” that sits beneath and alongside the investment engine. When capital formation intensifies — whether for a new fund, a new share class, or a new vehicle — the foundation is already strong.

The organization doesn’t scramble to assemble materials. The materials are already alive.

5. Consistency Becomes a Competitive Advantage

In a category where many managers under-communicate, consistency itself becomes a differentiator. Investors notice when materials feel modern. They notice when quarterly updates match the style and structure of the pitchbook. They notice when new acquisitions are announced clearly. They notice when the website reflects the real state of the portfolio. They notice when a firm has something to say about the cycle — and says it calmly and coherently.

This is not about overwhelming investors with frequency. It is about giving them enough touchpoints, delivered well, that the firm feels disciplined across time.

And discipline compounds.

When the next capital formation phase arrives — whatever that looks like for the vehicle — the path is clearer because the groundwork was not ignored.

The story was maintained.

The brand stayed alive.

Investors were never left to guess.

Closing Thought

Capital formation is easiest for managers who treat communication as a continuous discipline rather than a periodic exercise. Real estate investors of all kinds — institutions, family offices, advisors, high-net-worth individuals — respond to clarity and consistency across time. DG’s role is to make that possible, practical, and scalable, so teams can remain focused on the work they are uniquely equipped to do.

Capital formation rewards firms who remain present even between the peaks.

The Myth of the Perfect Name in Investment Management

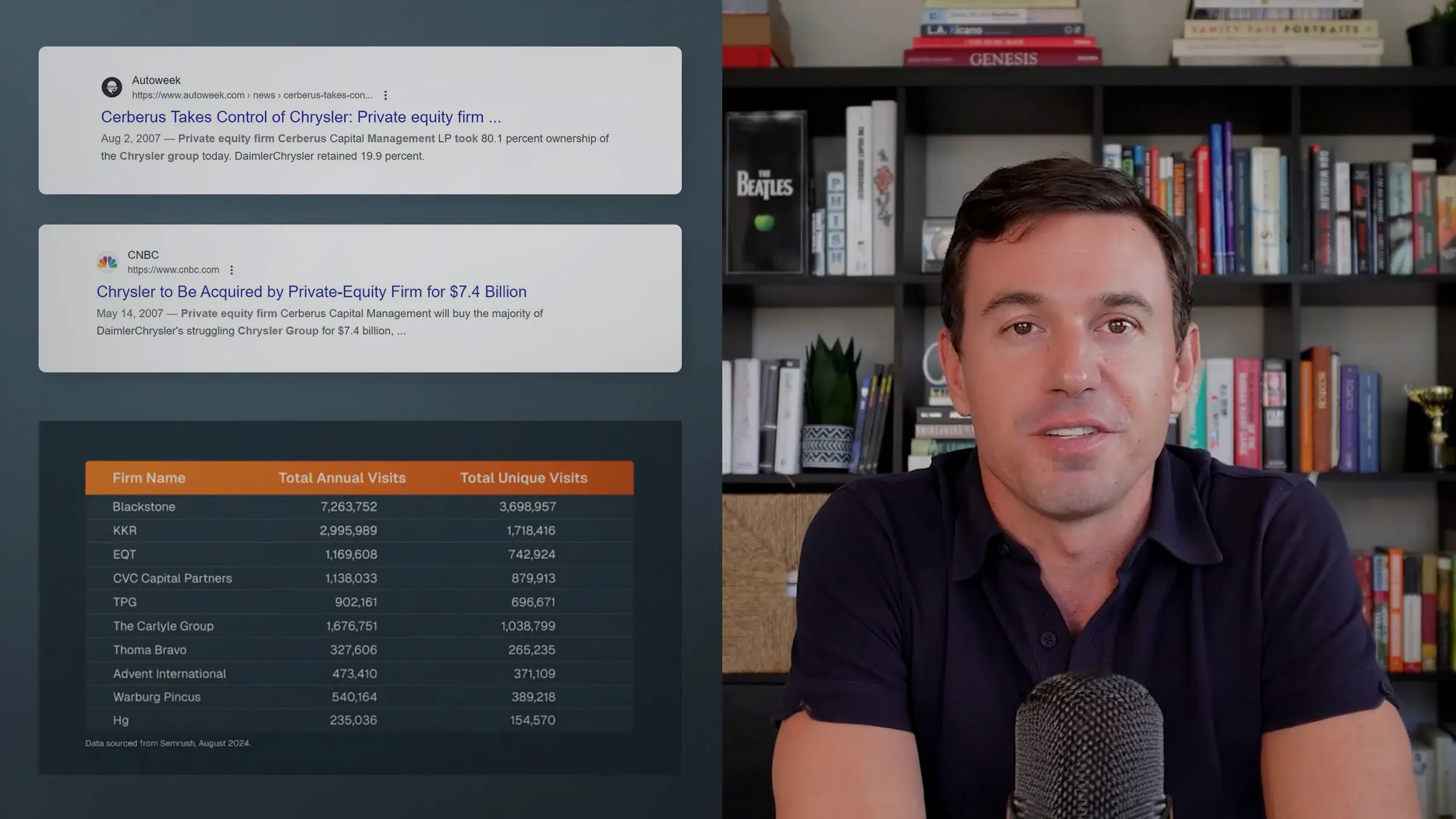

There’s a story about the founders of Blackstone that may or may not be true, but like all good stories in finance, it feels true enough to repeat.

In the mid-1980s, Steve Schwarzman and Pete Peterson were sitting in the living room of one of their homes, agonizing over what to name their new firm. They went back and forth for hours: Was “Blackstone” right? Did it sound too serious, too heavy, too cold?

At some point, one of their wives walked in and asked what on earth they were doing. They explained the debate. She listened and said something along the lines of:

“The name doesn’t matter. It’s going to take on whatever attributes you build into it through the business.”

I think that’s exactly the right way to think about naming.

Yes, some names are better than others. But in the end, a name is a totem, not a prophecy. It carries the meaning that you and your people build into it over time.

The Industry’s Long-Running Joke

Private equity and investment management have always had a bit of a naming problem — or maybe a naming formula. The old joke goes: When a new firm tries to name itself, every Greek god is already taken.

That’s only slightly an exaggeration. The Greek gods are taken, the mountain ranges are taken, the oceans are taken. There are plenty of Atlantics and Pacifics, more Summits and Peaks than anyone can count. Some names sound like marketing abstractions. Others turn out to be the founder’s childhood street.

The naming conventions are so narrow that, over time, they’ve become self-referential humor inside the industry.

And then there’s Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the gates of hell. To this day, I can’t hear that name without flashing back to seventh-grade Latin class, where our textbook introduced “Cerberus the dog” before I knew anything about private equity. There are exceptions to every rule, but that one remains… a choice.

The Decline of the Eponymous Firm

Over the past 10 or 15 years, we’ve seen a clear shift away from firms named after their founders. The reason is obvious.

First, it reads as egotistical. Most leaders don’t want to send that signal to their teams, their LPs, or the market.

Second, longevity. When a firm’s name is tied directly to one or two people, there’s an inevitable cognitive dissonance when those people retire, move into a chairman role, or pass away.

You can see the evolution all over the industry. The Jordan Company becomes TJC. Thomas H. Lee becomes THL. Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, thankfully, becomes KKR. These firms have the scale and history to make the acronym work. The rest of us would probably disappear into the alphabet soup.

Amusingly, even Blackstone is now often referred to simply by its ticker, BX. Maybe that’s the end state of all successful firms: eventually you become two letters and a stock price.

Why Naming Projects So Often Disappoint

Darien Group has been involved in probably a dozen significant naming projects over the years — usually for new firms or new funds. In the earlier days, we’d bring in professional naming agencies. These were the real deal: they’d worked with major corporations, had linguists and cultural researchers on staff, and could talk for hours about phonemes, etymology, and word shape.

And yet, even with all that science behind them, the results were often unsatisfying. The client would nod politely, we’d circulate long lists of “rationales,” and somehow everything felt off. Half the time, we ended up reverting to something the client came up with themselves — or something that emerged spontaneously during a call.

Which brings me to one of my favorite examples.

How “Heartwood” Was Born

In the mid-2010s, we worked with a private equity firm that had been operating since the early 1980s. Its original name, Capital Partners Incorporated, had been perfectly serviceable for its era. But by 2015, it had the feel of something chosen quickly at formation and never revisited — more generic than intentional, and out of step with what the firm had become.

The firm needed to rebrand. Its differentiator was in how it structured acquisitions: rather than loading companies with five to seven turns of debt, it preferred two or three, sharing more cash flow with management and investors. That was a selling point for founder-led and family-owned businesses.

We hired a professional naming agency to help, and a month in, the client still hated every option. On a Friday morning before a call with them — where we had nothing new to present — I started thinking about metaphors for solidity. I googled “diagram of a tree trunk.”

It turns out a tree has five concentric layers. The innermost, densest layer is called heartwood — the core that provides the trunk’s strength.

Fifteen minutes later, we had a name that perfectly captured the firm’s philosophy: structural strength at the center, reliability for both investors and management teams. It wasn’t flashy, but it had integrity and metaphorical resonance.

That’s usually what works.

The Illusion of “Scientific” Naming

The irony of the naming industry is that it pretends there’s a formula. There isn’t.

Even with today’s tools, ChatGPT included, you can generate a hundred plausible names in five minutes. The trick is not generation; it’s judgment. Which one feels like your firm? Which one you can say out loud without wincing? Which one will sound credible in a partner meeting or on a pitch deck?

At the end of the day, I agree with the Blackstone anecdote. The name becomes whatever meaning the firm builds into it. You can have the greatest name in the world, but if you underperform, it will eventually sound cheap. You can have a pretty bad name and, if you succeed, it will start to sound timeless.

What Actually Matters

So, what makes a name good?

- Ownability. It has to be available — trademark, URL, and search results. One new client we worked with launched a site and was baffled that they weren’t showing up on Google. The problem? Their name was nearly identical to a much larger financial institution overseas. That’s like naming yourself “Nike Equity” and expecting to rank.

- Appropriateness. The tone should match your audience. If you’re a middle-market industrial investor, a name like “Quantum Axis Capital” probably oversells the sophistication. Conversely, “Smith Capital” underplays it.

- Comfort. You have to like saying it. You’ll say it thousands of times a year.

Everything else is taste.

The Role of Brand and Narrative

The reason names still matter is that they’re shorthand for a broader story. A name opens the door; the brand narrative walks people through it.

Choosing a name is an act of positioning; it hints at personality, time horizon, and risk tolerance. A strong brand and narrative make that positioning explicit. That’s what differentiates one manager from another when everyone is competing for the same dollar of capital.

Brand, narrative, reputation, and story are all tools for outcompeting in a crowded market. You can’t own a better Greek god, but you can own a clearer message.

A Totem, Not a Strategy

I’ve come to see naming as a strangely emotional process for clients. It’s personal. It feels like destiny. But really, it’s just the first line of a longer story.

A name is a totem, not a strategy. Pick something you can own, pronounce, and stand behind. Make sure it’s not already taken. Beyond that, stop agonizing.

Because if your firm performs well, the name will come to mean excellence. And if it doesn’t, even the perfect name won’t save you.

When you ask an emerging manager to describe their narrative, they usually talk about their strategy. Not the structure of the story — the story itself. They talk about the sourcing edge, the operational orientation, the sub-sector they understand more deeply than their peers. And all of that matters. But a narrative isn’t a thesis. It’s an architecture. And the place where that architecture is built first — long before the pitchbook — is the website.

A Fund I or Fund II website forces discipline in a way that verbal explanations simply don’t. You can talk for 20 minutes and clarify yourself halfway through the sentence. The website doesn’t grant that grace. It exposes the logic of your story instantly: whether the category is clear, whether the thesis grows naturally out of that category, whether your point of view has sharp edges or is still in draft form.

In this sense, your website becomes the dress rehearsal for the narrative itself. It reveals whether the GP truly knows how to sequence the story — or whether they’re hoping eloquence will compensate for structural weaknesses.

1. Narrative Begins With Category, Not Strategy

If there is one universal mistake emerging managers make in digital storytelling, it is skipping the category. They rush into the strategy: the sourcing channels, the underwriting criteria, the deal filters. LPs can’t absorb any of that until they know what universe they’re in.

The website is where the category must be established cleanly:

- What market are we in?

- Why does this market make sense now?

- What do LPs routinely misunderstand about it?

Only once the category is established does the strategy make sense. This is not semantics; it’s cognition. If the category is blurry, the strategy floats in midair. If the category is crisp, the strategy feels inevitable.

In film, you don’t start a story in the middle of Act II. You establish the world first. Emerging managers forget this constantly. The website cannot.

2. The Strategy Needs to Feel Like the Logical Response to the Category

Once the category is clear, the strategy needs to emerge naturally from it — as if no other strategy could possibly make as much sense. This is the quiet part of narrative that creates conviction: why this GP, in this market, at this moment.

Emerging managers often lose this thread. They describe a strategy that is interesting but not obviously connected to the market conditions they just described. There’s a gap between premise and conclusion. LPs feel that gap instantly.

A strong website narrative makes the logic chain impossible to miss:

- “This is the market.”

- “This is the inefficiency or mispricing.”

- “This is the edge that exploits it.”

When that chain feels sturdy, LPs begin listening at a different altitude. The story becomes a structure rather than a collage.

3. Clarity and Compression Are Digital Forms of Maturity

Talking allows you to wander; writing does not. When emerging managers begin structuring their website copy, they often discover the story they’ve been telling verbally doesn’t survive compression. It requires too many caveats, too many side explanations, too many footnotes about “how this category really works.”

LPs interpret this fragility as a lack of coherence. They’re not wrong.

A Fund I narrative should survive a two-paragraph summary. If it can’t, it probably won’t survive institutional translation.

This is why the website’s constraints matter. They force the GP to decide:

- What truly belongs in the story?

- What is support rather than center?

- What is noise that needs to be cut?

Compression is not a sacrifice — it’s a revelation of what actually matters.

4. Emerging Managers Must Choose Their Edge Early

Digital storytelling requires prioritization. LPs remember one or two things about you, not eight. Emerging managers often try to lead with all of their advantages: sourcing, operating depth, team chemistry, thematic insight, differentiated networks.

A website that presents five edges communicates none.

The narrative needs to surface the one edge that is both:

- believable, and

- durable.

Every other detail should reinforce that edge rather than compete with it.

It’s similar to directing: a debut filmmaker does not introduce eight subplots. They introduce one story, cleanly told, with a point of view so clear you could recognize it in their next film. Emerging managers need the same discipline.

5. Narrative Consistency Across Digital Touchpoints Signals Institutional Readiness

When LPs see a website, they immediately triangulate it with:

- the deck

- the bios

- the introductory email

- the data room

- any content you’ve published

If these elements do not agree with each other — if the tone shifts, if the vocabulary changes, if the strategy language is more mature in one place than another — LPs assume the narrative is still forming. They don’t need the story to be perfect, but they need it to be stable.

Emerging managers often update the deck frequently but leave the website frozen at an earlier stage. LPs experience that mismatch as dissonance.

“Which version is real?”

If the GP doesn’t know yet, the LP won’t know either.

The narrative has to age consistently. Otherwise it will never compound.

Closing Thought

For emerging managers, the website is not a brochure. It is the first evidence of whether the GP understands the architecture of their own story. Clarity, category, edge, proof, sequencing — these aren’t copywriting choices. They’re structural choices. LPs notice when the structure is sound. They notice faster when it isn’t.

The managers who break through are rarely the ones with the flashiest sites or the most dramatic taglines. They’re the ones whose digital narrative feels like the clean first chapter of a story that could plausibly build for the next decade. And LPs, whether they say it out loud or not, are future-oriented people. They want to believe they’re meeting a director at the beginning of a long career — not someone still searching for their opening scene.

Emerging managers rarely misunderstand how hard fundraising will be. Most walk into the process knowing they will hear “no” far more often than “yes.” What they underestimate — almost universally — is why it’s so hard, and what specific frictions slow them down even when the underlying strategy is strong.

A Fund I or Fund II raise is not simply a test of strategy, pedigree, or past experience. It’s a test of timing, narrative clarity, emotional resilience, and the ability to make LPs remember the right three things when they talk about you later. What derails most emerging managers is not the absence of quality. It’s the presence of avoidable misunderstandings about how LPs actually make judgments in the early stages.

This post breaks down the structural reasons emerging managers struggle, based on hundreds of fundraises and a fair number of lessons learned the hard way.

1. The Starting-Point Illusion: Pedigree and Past Deals Don’t Travel as Well as GPs Expect

Many emerging managers assume that their resumes and prior deal experience will do more of the heavy lifting than they actually can. Pedigree is useful — it gets attention and establishes general credibility — but it is rarely persuasive on its own. LPs are not allocating to résumés. They are allocating to the future ability of a team to execute a strategy with discipline.

Past deals present an even more nuanced challenge. Most emerging managers cannot claim attribution for their prior firm’s investments, which means they cannot present those transactions as formal track record. They can gesture toward them, contextualize them, and weave them into the narrative, but LPs understand the distinction between experience in the ecosystem and ownership of outcomes. Without attribution, deal history tends to function more as background color than as evidence, and emerging managers often overestimate its persuasive power.

In other words, pedigree and past deals help — but only when they support a clear, forward-looking story. They are not the story.

2. What LPs Actually Perceive (and Why It Surprises Emerging Managers)

Emerging managers tend to assume that if they explain their strategy thoroughly, LPs will come away with a firm grasp of who they are and what makes them distinct. In reality, LPs are scanning for a small number of memorable, repeatable ideas — something they can summarize to a colleague in a hallway conversation later.

This creates a simple test:

Can someone who is not an expert describe your strategy in three sentences, without losing the plot?

Most emerging managers dramatically overestimate how well their complexity will travel. What they see as essential nuance often becomes noise. What they see as obvious differentiation often blends into a category LPs perceive as crowded.

LPs are not dismissive; they are overloaded. The burden falls on the GP to create a story that is not just accurate but portable — something that survives outside the room.

3. The Timing Problem: Everything Takes Longer Than Anyone Admits

The other major underestimation is timing. Not just in the sense of “fundraising takes longer than we thought,” but in the deeper sense that momentum develops slowly, unevenly, and often invisibly for long stretches.

Fund I and Fund II fundraises almost never follow a neat pipeline. They move in fits and starts. At BKM Capital Partners in 2014, the expectation was a $25–50 million anchor from friends and family. Instead, those channels produced a fraction of that amount. The turning point was a single meeting with a Scandinavian LP who happened to be in Los Angeles for one day. We were taking twenty meetings a week. That was the one that mattered.

The lesson wasn’t that we mis-executed. The lesson was that the path is nonlinear. You can influence consistency and preparation; you cannot choreograph when conviction arrives or from where. Emerging managers almost always underestimate the lag between doing the work and seeing the results.

4. A Lesson From BKM: Compression, Clarity, and the Danger of Taking Too Long to Get to the Point

The experience at BKM also revealed another common challenge: emerging managers often bury the lead of their own strategy. The multitenant industrial thesis was compelling, differentiated, and, as it turned out, highly scalable. But it took twelve slides to explain why. Looking back, there was probably a three- or four-slide version of the same argument that would have landed more powerfully.

Part of the issue was communicative style. The founder, Brian Malliet, was a deeply capable operator with an instinct for detail and precision. His explanations were thorough, logical, and grounded in fact — but not distilled. At the time, I didn’t push back as strongly as I would today. Now, after a decade of seeing how LPs actually process information, it’s clear that emerging managers often undermine themselves by overexplaining.

Compression is not simplification; it is discipline. It forces clarity about what truly matters, and it respects the LP’s cognitive load. Emerging managers who master compression tend to gain traction faster because they surface the essence of their strategy instead of making LPs work to find it.

5. The Market Is Often Wrong About What’s “Investable”

One of the most valuable lessons from working across strategies is that consensus about what is “institutionally investable” is often temporary. LPs misjudge this just as frequently as GPs do.

Examples are everywhere:

- In the 1990s, corporate divestitures were considered unattractive, yet Platinum Equity built an entire franchise by acquiring orphaned divisions that nobody else wanted.

- In 2014, multitenant industrial was widely viewed as too operational and too messy — yet BKM turned that stigma into outperformance.

- Entire categories that were once considered fringe or non-scalable have since become mainstream allocation themes.

The takeaway is not that every contrarian idea is good. It’s that the market’s current beliefs about what is or isn’t “institutional” should not be treated as permanent truths. Many emerging managers overcorrect by trying to present themselves as consensus-aligned, when in fact their edge may lie in something the market does not yet fully appreciate.

6. The Emotional Reality: Fund I Is Mostly Rejection, and That’s Normal

The final underestimation is emotional. Fund I requires hearing “no” far more times than most people have prepared themselves for. When I was raising for BKM, it was surprising how similar the emotional cadence felt to building Darien Group years later. In both cases, you had to pitch a dozen prospects to get one serious conversation.

Rejection at this stage is not diagnostic. It is structural.

The challenge is not to avoid rejection; it is to persist long enough that the small percentage of conversations with real potential can actually happen.

Closing Thoughts

Emerging managers don’t struggle because they lack intelligence, experience, or ambition. They struggle because they misjudge what LPs truly react to: timing, clarity, memory, simplicity, and legitimacy. These are solvable problems, but only if GPs understand the dynamics at play.

A strong strategy is necessary.A clear story is differentiating.But the managers who break through are the ones who recognize that Fund I is not a referendum on their potential — it is the beginning of a longer institutional arc, one shaped as much by discipline as by opportunity.

A Modern Reference Guide for Private Equity, Credit, Real Estate, Venture Capital, and Broader Alternative Investment Managers

Marketing, branding, and communications have become strategic capabilities across the entire investment management landscape. Private equity firms, credit platforms, real estate managers, venture funds, hedge funds, and emerging managers increasingly rely on digital presence, narrative clarity, and institutional communications to compete for capital, deals, and talent.

Yet, many investment professionals are less familiar with the terms, tools, and frameworks used by modern marketing teams, agencies, and digital specialists.

This dictionary is designed to bridge that gap. It defines the language of investment management marketing, covering brand strategy, digital communications, investor relations, content strategy, and AI optimization. It is intended for GPs, IR teams, marketing leaders, and emerging managers building a more strategic and scalable marketing function.

A

A/B Testing

A structured comparison between two versions of content or design. Used by investment managers to refine fundraising emails, website CTAs, and sourcing campaigns.

AI Optimization

Preparing digital content so AI models (Google, ChatGPT, Perplexity) interpret it accurately. Increasingly important for investment managers seeking visibility among allocators and founders.

Attribution Modeling

A digital analytics method that determines which touchpoints drive engagement. Helps GPs and managers understand if LPs find them through search, content, email, or LinkedIn.

B

Brand Architecture

Defines how a firm’s strategies, funds, and platform initiatives relate to each other. Essential for multi-strategy investment managers and diversified alternative asset managers.

Brand Positioning

The core narrative that explains who the firm serves, what makes it different, and how it invests. The foundation of all investment manager marketing.

Brand Systems

The full ecosystem of visual and verbal elements that ensure consistency across all materials. Includes typography, color systems, layout grids, iconography, data visualization standards, messaging hierarchy, and tone guidelines. A strong brand system ensures LP letters, pitch decks, websites, and portfolio communications feel unified and institutional.

C

Capital Narrative

The overarching investment story that ties together strategy, differentiation, and value creation. Critical for pitch decks, websites, and fund marketing.

Conversion Rate

The percentage of website or campaign visitors who complete an action. Key metric for optimizing investment firm websites and digital funnels.

Content Calendar

A structured schedule for distributing thought leadership, insights, portfolio stories, and announcements across channels.

CRM Hygiene

Maintaining accurate data in platforms like DealCloud, Affinity, Salesforce, or HubSpot. Ensures alignment between marketing, IR, and deal teams.

D

Data Visualization Standards

A consistent design system for charts showing IRR, MOIC, performance, loan characteristics, or portfolio metrics. Enhances LP readability.

Demand Generation

Creating awareness and interest among LPs, founders, intermediaries, and recruits. Driven through LinkedIn, newsletters, SEO, and digital campaigns.

Digital UX Audit

A review of an investment manager’s website to evaluate clarity, structure, speed, navigation, and messaging.

E

Editorial Guidelines

Standards for tone, voice, and writing conventions across a firm’s materials. Ensures consistency across decks, letters, websites, and insights.

Evergreen Content

Long-lasting content like sector theses, investment philosophy, and FAQs. Strong for SEO and AI discoverability.

F

First Fold

The visible portion of a webpage before scrolling. Crucial for communicating an investment manager’s positioning and differentiation.

Funnel Strategy

A structured sequence that guides LPs or founders from awareness to engagement. Useful across fundraising, thought leadership, and recruiting.

G

Gated Content

High-value content that requires an email submission. Investment managers use it for research reports, thematic insights, and recruiting tools.

Google Search Console

A platform used to analyze search performance and identify optimization opportunities on firm websites.

H

Hero Statement

The headline on a homepage that communicates the firm’s differentiator in one sentence. A critical element of investment manager website design.

House Style

A standardized writing system that ensures consistency across all institutional communications.

I

Information Hierarchy

The structured flow of information that makes complex investment stories easy to follow. Central to website UX and fundraising decks.

Investor Communications Strategy

The planned cadence and structure of letters, updates, reports, and presentations delivered to LPs.

J

Journey Mapping

A visualization of how LPs, founders, borrowers, or intermediaries interact with the firm across digital and offline touchpoints.

K

Keyword Strategy

The selection of search terms that investment managers should optimize for. Directly tied to SEO strategy, AI visibility, and content planning.

Knowledge Graph

How Google and AI models understand the firm as an entity. Shaped by consistent content, metadata, backlinks, and structured data.

L

Landing Page

A single-purpose webpage built to drive a specific outcome. Investment managers use landing pages for events, reports, or recruiting.

Lead Scoring

A method for evaluating which prospects are most likely to engage. Useful in deal sourcing and institutional fundraising workflows.

M

Messaging Framework

A structured system that anchors how a firm communicates its strategy, track record, investment criteria, and value creation approach.

Microsite

A standalone site used to showcase a fund launch, AGM, platform milestone, or thematic investment insight.

Motion Graphics

Animated visuals used for websites, videos, and digital content to convey complex investment topics more dynamically.

N

Narrative Architecture

The underlying structure of a story across decks, websites, or insights. Ensures clarity, cohesion, and strategic flow.

Net New Audience

Any new LP, founder, borrower, or partner segment the firm is targeting.

O

On Page SEO

Optimizing website content, headers, metadata, and internal links to increase organic search visibility for investment managers.

Owned Media

Content assets controlled directly by the firm, such as websites, newsletters, insights, and video libraries.

P

Paid Media

A marketing strategy where investment managers use paid channels such as LinkedIn ads, Google search ads, sponsored content, or targeted industry placements to increase visibility. Often used for recruiting, event promotion, thought leadership amplification, and brand awareness campaigns. Paid media complements organic content and is increasingly used by emerging managers to reach LPs or founders who may not already follow the firm.

Pillar Page

A long-form content asset that anchors an SEO topic and links to supporting content. Helps investment managers dominate search terms related to key strategies, sectors, or thought leadership themes.

Q

Quarterly Content Rhythm

The planned cadence for distributing insights, updates, or thought leadership on a quarterly basis.

Qualifying Traffic

Website visitors who align with intended institutional audiences.

R

Retargeting

Showing follow-up content to users who already visited the website. Effective for recruiting, LP nurture campaigns, and event promotion.

Revision System

A structured process for managing version control and feedback across decks, websites, and reports.

S

Sector Page

A specific webpage explaining a firm’s expertise in a particular sector. Often SEO optimized to attract LPs, founders, or counterparties.

SEO Schema

Structured data that improves how search engines and AI models interpret a firm’s content.

Sourcing Narrative

Messaging that explains how the firm finds opportunities. Key across private markets.

T

Thought Leadership Framework

A structured approach for producing insights that reinforce the firm’s expertise. Central to content marketing for investment managers.

Tone of Voice Framework

Guidelines that ensure writing consistency across communications created by different contributors.

U

UX Wireframe

A blueprint for a webpage that maps layout and structure before design.

User Intent

The underlying purpose behind a search query. Key for SEO targeting in investment management.

Unique Selling Proposition (USP)

The specific attributes or differentiators that set an investment manager apart. A USP might include sourcing advantages, team structure, sector specialization, value creation model, operational resources, or geographic focus. USPs inform brand positioning, messaging frameworks, website content, and pitchbook structure, helping the firm articulate why LPs, founders, or intermediaries should choose them over comparable managers.

V

Video Strategy

A plan for using video to support deal sourcing, recruiting, fundraising, and institutional visibility.

W

Website Architecture

The structure and navigation of an investment manager’s website. Influences SEO, brand perception, and the LP experience.

Website Speed Optimization

Improving load time, mobile performance, and technical health for better SEO and user experience.

Z

Zero Click Content

Content that communicates value directly inside platforms like LinkedIn and Google without requiring a click. Important for increasing brand visibility with allocators and founders.

Closing

This dictionary is a foundational reference for investment managers navigating modern marketing, digital presence, and institutional communications. As LP expectations evolve and digital channels become central to fundraising and sourcing, firms that invest in clear narratives and strong marketing infrastructure gain a measurable competitive advantage.

Darien Group specializes in branding, websites, messaging, and investor communications for investment managers across private equity, private credit, venture capital, real estate, and alternative investments. If your firm is evaluating a refresh or building scalable marketing capabilities, our team would be happy to help.

Emerging managers often underestimate the importance of their website not because they’re naïve, but because they assume LPs will begin forming judgments during the meeting. LPs don’t operate that way. The first impression happens before the relationship begins — specifically, at the moment an LP types your name into a browser. That visit is not just a glance. It’s a micro-evaluation of your readiness to step into the institutional world.

And because emerging managers haven’t been in the market long — Fund I, Fund II, a newly announced strategy with a small team — the name itself carries no history. No reputation precedes you. The website becomes the origin point of your institutional story. LPs know this, and they treat it as such.

When I talk about digital presence with early-stage managers, I often describe the internet as a galaxy: billions of stars, clusters, gravitational pulls. A brand that has existed for 30 years already has its galaxy — its residues, artifacts, historical clutter. A new manager has none of that. You get to launch a fresh star system. LPs are looking to see whether the constellation you’re building makes sense.

1. LPs Are Not Looking for Perfection — They’re Looking for Readiness

LPs don’t judge emerging managers the way emerging managers judge themselves. The GP is often thinking about what the site “says.” LPs are scanning for what the site implies.

Questions they ask intuitively:

- Does this firm understand its category?

- Does the digital presentation reflect how serious the strategy is supposed to be?

- Does this feel like the starting point of something real?

A polished site doesn’t guarantee readiness. But a sloppy one almost always signals unreadiness. LPs are evaluating whether you’ve made intentional choices — not extravagant ones, but thoughtful ones. That alone separates you from most early-stage peers.

This is the first moment LPs decide whether a manager is “real” or “not yet.”

2. Your Website Creates the Emotional Frame for the Entire Relationship

The website is almost always the first emotional contact point an LP has with a new manager. It tells them:

- whether you are confident,

- whether you understand your own story,

- whether you are leaning into your newness or hiding from it,

- and whether there is actually a strategy worth hearing.

Emerging managers often forget how powerful newness is. LPs don’t meet many managers in their twenties or thirties who are building funds. And when they do, they want that energy. They want to believe they’re seeing the beginning of something that could scale. That optimism is an asset — if the website uses it thoughtfully. A conservative, too-traditional digital presentation erases one of the few natural advantages an emerging manager possesses.

In the arts, the most exciting filmmakers and musicians are rarely the oldest ones. Markets behave similarly. When a manager’s digital identity communicates intelligence, discipline, and freshness simultaneously, LPs tune in fast.

3. Single-Scroll Sites Work Because They Respect the LP’s Attention

For emerging managers, a single-scroll website is not a compromise. It’s often the correct architecture. Smaller teams, minimal track records, and early-stage stories rarely justify multipage sprawl. LPs prefer clarity over volume, and coherence over breadth.

A single-scroll site:

- forces narrative discipline,

- prevents empty pages (“Portfolio,” “Team”) from signaling fragility,

- organizes the story in a digestible sequence, and

- conveys confidence rather than apology.

LPs don’t penalize smallness. They penalize sloppiness, inconsistency, and premature scaling.

A well-done single-scroll site says, “We know exactly who we are at this stage.”

That is a very compelling signal.

4. The Case Against Cheap Websites (and Why LPs Notice)

(One of the two posts where this argument will appear)

Many emerging managers go the inexpensive route at the beginning — a $2,000 template site, a freelancer overseas, or a Squarespace build put together between other tasks. Technically, this can work. But strategically, it introduces four problems that LPs pick up immediately:

- You’re delaying the introspection that the real website forces.

A proper site requires clarity: What is our category? What do we believe? What do we want people to remember? Cheap sites let you dodge that work — and LPs can tell. - You’re going to rebuild it in 12–18 months anyway.

Why race with a sprained ankle when you could start healthy? - You squander dozens of early impressions.

In Fund I, you don’t have the luxury of B-minus impressions. One strong early impression can change a firm’s trajectory. - The founder ends up doing the work.

No emerging manager has extra time. Trying to micromanage a designer who doesn’t understand institutional capital is a bad use of a scarce resource.

Cheap doesn’t always mean bad. But cheap almost always means unfinished. LPs can feel that immediately.

5. LPs Don’t Just “See” the Website — They Infer the Organization Behind It

When LPs look at your website, they aren’t judging your taste. They’re judging your discipline. A website is the first operational artifact LPs encounter. They assume:

- organized site → organized fund

- coherent design → coherent underwriting

- clear copy → clear thinking

- sloppy execution → sloppy diligence

- mismatched elements → emerging team not yet aligned

None of these correlations are perfect. But LPs don’t need perfect correlations. They need enough signal to decide whether it’s worth spending time.

Closing Thought

Emerging managers start at a structural disadvantage: limited track record, small team, thin footprint. The website is one of the only tools that can reverse that disadvantage quickly. Not by pretending to be a billion-dollar platform, but by demonstrating clarity, narrative discipline, and readiness.

Before LPs hear your strategy, they experience your digital identity. And in Fund I fundraising, that difference — between the GP who treats the website as part of the institutional story and the GP who treats it as a formality — often determines who advances to the next conversation.