.jpg)

Private Equity Insights

Darien Group exists to bridge the gap between exceptional design capabilities and private equity communications. Our library of resources serves as a practical guide for firms looking to refine or redevelop their brand and ensure their story resonates with target audiences.

Featured Videos

Emerging managers often assume their digital presence is a supporting detail — a credibility checkbox, a place to house the team bios and the contact form, something LPs will glance at briefly before the real conversation begins. In reality, LPs make meaning out of digital signals long before they make meaning out of strategy. For most emerging managers, the website, the footprint around it, and even small digital behaviors function as a quiet pre-meeting filter. LPs start forming judgments before the first Zoom call is scheduled.

This is not because LPs are superficial. It is because they are overloaded. Most institutional allocators are tracking dozens of managers at any given time, fielding dozens more inbound, and monitoring a saturated pipeline where the differences between strategies are often subtle. They cannot begin each relationship from zero. They use digital cues to determine whether a manager is ready for institutional conversation — or whether the GP still has work to do.

Emerging managers regularly underestimate how much of the “legitimacy gap” is closed or widened before they ever speak.

1. LPs Judge the Website Far Earlier and More Harshly Than Managers Expect

When an LP first hears your name — from a warm intro, a conference, a placement agent, or a colleague — they do the same thing everyone else does: they search you. The website is often the moment where the LP decides whether they are dealing with an institutional player or a first-time founder still finding their footing.

The website’s job is not to impress. It is to reduce uncertainty. LPs are looking for signals that you understand where you are in your institutional arc: clear strategy language, mature design restraint, coherent structure, and clean articulation of the category. Anything that feels improvised, inconsistent, or overly promotional triggers doubt. LPs don’t need you to be a billion-dollar platform, but they need to see signs of discipline.

Among emerging managers, the most common misstep is assuming the website is “good enough” because it looks modern. LPs don’t evaluate modernity. They evaluate coherence.

2. Tone Matters — Even When You Think It Doesn’t

LPs read tone before they absorb content. A website that leans too heavily on marketing language (“world-class deal flow,” “unparalleled access,” “industry-leading expertise”) suggests the manager is trying to make up for a lack of substance. A website that feels like a real estate developer’s landing page suggests transactional orientation rather than investment discipline. A website that reads as overly academic or jargon-heavy suggests the GP might be clearer in their head than in their communication.

Tone is not decoration. It tells LPs whether the manager communicates at the altitude institutional investors expect. Emerging managers often reveal more than they intend through tone: their anxieties, their need for validation, or their attempts to sound “institutional” rather than being institutional.

Tone is a psychological tell. LPs are very good at reading it.

3. Digital Behavior Signals Operational Maturity

Digital presence isn’t limited to the website. LPs form impressions from:

- whether bios are complete and up to date

- whether updates are posted consistently or sporadically

- whether fund materials feel coordinated

- whether email signatures match the website’s tone

- whether the firm shares insights or only transactional announcements

These are small signals, but they shape the LP’s sense of whether the GP is building a durable organization or improvising around the edges.

For emerging managers, inconsistency carries a disproportionate cost. LPs assume inconsistency in digital presentation may indicate inconsistency in process. The opposite is also true: even modest digital discipline can signal that the GP is thoughtful, prepared, and capable of building institutional trust over time.

Digital behavior is the operational equivalent of body language.

4. LPs Look for Patterns — Not Perfection

Emerging managers sometimes worry that their website is not on par with established funds. The truth is that LPs don’t expect perfection from a Fund I. They expect pattern recognition. They are looking for whether the manager’s words, materials, and digital presence all support the same thesis. Does the strategy described in the deck match the strategy described online? Do the bios reinforce the specialization the pitchbook emphasizes? Does the visual identity feel like it belongs to the category the GP claims?

When these patterns align, LPs assume the GP thinks clearly and is building something real. When the patterns clash, LPs assume the opposite.

This is why digital presence is not about impressiveness. It is about congruence.

5. The Subtle Signals That LPs Pick Up Instantly

LPs rarely articulate these, but in practice they react strongly to:

- websites with mismatched visual languages

- pitchbooks that look like they were assembled in pieces

- founders who use different terminology on their site than in their deck

- firms whose About section could describe any other emerging manager

- strategies that feel hedge-like in writing but private equity-like in design

- overly clever taglines or design flourishes that feel out of place

None of these signals prove that a GP is unprepared. But together, they shape the LP’s subconscious impression. Emerging managers often think these details are trivial. LPs treat them as evidence.

The design system around your strategy is not judged aesthetically — it is judged psychologically.

Closing Thought

Digital presence is the first chapter of your institutional story. Emerging managers often imagine that LP conviction is built through meetings, decks, diligence, and reference checks. In reality, LP conviction begins much earlier — in the 30 seconds they spend on your website before deciding whether to schedule the meeting at all.

Digital behavior is not an afterthought. It is the first impression, the early filter, and often the difference between an LP leaning in or moving on. Emerging managers who treat it as part of their narrative, rather than the packaging around it, close the legitimacy gap faster than those who don’t.

How thesis-forward, portfolio-forward, and platform-forward architectures shape investor comprehension

A real estate manager’s website is often the first extended interaction an allocator, advisor, or prospective partner has with the platform. It is also one of the few brand touchpoints that must serve multiple audiences simultaneously: investment professionals, intermediaries, potential recruits, and sometimes retail investors, depending on the product set.

Across the industry, three website structures appear consistently because they help users understand who the manager is, what they do, and how to navigate the information. While each structure has strengths, their effectiveness depends heavily on strategy breadth, product complexity, and the firm’s communication priorities.

At DG, we see the three core architectures, not because firms are imitating one another, but because these formats tend to improve clarity and user experience.

1. Thesis-Forward Design

Best for managers with a clear investment philosophy or a distinctive point of view

A thesis-forward website places the firm’s worldview at the center of the experience. Visitors encounter a clearly articulated approach to the market, often supported by cycle-aware reasoning, targeted sector perspectives, or a defined sourcing framework.

This structure is most effective for:

- Sector-specialist managers

- Emerging managers seeking early differentiation

- Strategies that rely on a proprietary lens or operating insight

- Firms where narrative clarity is core to the value proposition

- Managers with diverse strategies that can be difficult to relate to one another

Why it works

A thesis-forward site gives users immediate orientation: what the manager believes about the market and why their approach makes sense right now. For allocators who evaluate strategies through the lens of fit and coherence, this format helps establish context before details.

What to watch for

Because the thesis sits front-and-center, it must be well-structured and measured, avoiding overly declarative market statements. Retail-facing managers, in particular, benefit from balancing thought leadership with plain-language explanation.

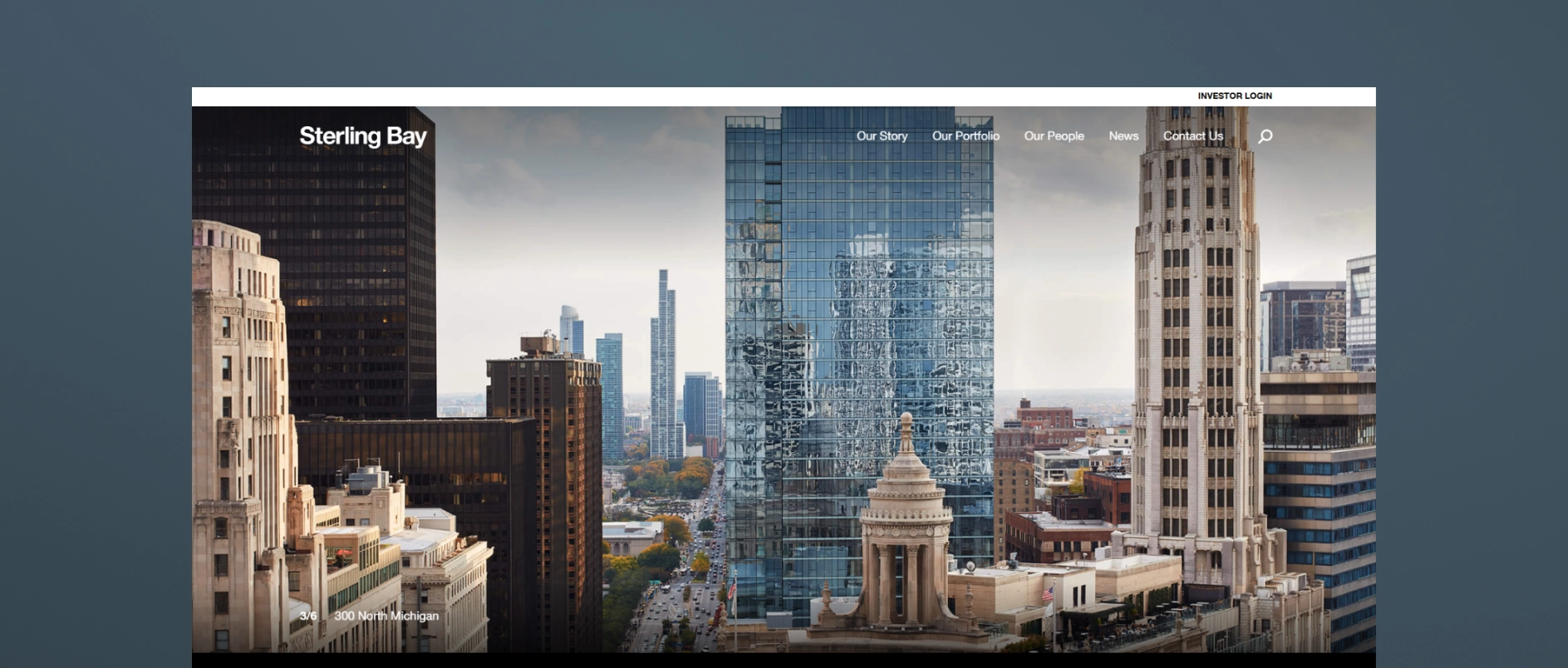

2. Portfolio-Forward Design

Best for managers whose track record, asset examples, or execution capabilities are the primary differentiators

Portfolio-forward websites surface real projects early, not to showcase volume, but to contextualize how the strategy works in practice. The “portfolio” becomes the interpretive tool that helps visitors understand markets, risk posture, and operating capabilities.

This structure is most effective for:

- Vertically integrated or operator-oriented platforms

- Firms with meaningful asset diversity

- Strategies where real-world examples clarify the thesis more than narrative alone

Why it works

For some strategies, especially value-creation or development-heavy approaches, seeing selected projects helps users grasp scale, geography, and execution style more clearly than text descriptions.

The strongest implementations avoid presenting large photo galleries; instead, they combine:

- high-level asset cards,

- abbreviated business plans,

- standardized metrics (e.g., square footage, use type, region), and

- links to deeper strategy pages.

What to watch for

Portfolio-forward design requires disciplined curation. Too many projects, inconsistent photography, or large variances in detail can create noise. Retail-facing programs also need to ensure disclosures accompany any performance references appropriately, often influencing layout.

3. Platform-Forward Design

Best for multi-strategy managers or firms with complex distribution channels

Platform-forward websites organize the experience around the structure of the firm itself: its teams, product vehicles, capabilities, and operating subsidiaries or affiliates. This format acts as a directory, helping users understand where they should navigate based on their needs.

This structure is most effective for:

- Managers with institutional and wealth-channel products

- Firms offering multiple strategies (core, income, development, opportunistic, sector vehicles)

- Large organizations where team, scale, or infrastructure is a primary signal of readiness

Why it works

Platform-forward sites help visitors self-select: institutional LPs may head toward strategy pages, advisors may navigate toward product microsites, and prospective talent may go to careers or culture pages. This format supports clear segmentation without complexity.

Public examples, including large diversified real estate firms, often use this model because it scales well across product types and allows microsites to sit cleanly alongside parent-brand pages.

What to watch for

Platform-forward structures depend heavily on navigation clarity. Without intuitive menus, users may feel uncertain about where to begin. For wealth-channel products, creating a clear “Advisor Resources” path or standalone microsites avoids crowding the institutional narrative.

How to Choose the Right Structure

Align the website architecture to strategy complexity, audience mix, and communication goals

Choosing among these three models is less about preference and more about determining which architecture helps an audience understand the firm with the least friction.

Use Thesis-Forward when:

- The differentiator is how you think, not how many strategies you offer

- You are an emerging manager or a sector specialist

- Your thesis provides meaningful context for interpreting performance or portfolio decisions

Use Portfolio-Forward when:

- Real examples illustrate the strategy better than abstract explanation

- You want to highlight vertical integration or operating capability

- The assets themselves help clarify scale, market focus, or execution style

Use Platform-Forward when:

- You need to serve multiple audiences with different needs

- Your offerings span institutional LPs, advisors, and/or retail investors

- Complex products require separate microsites or tailored disclosure frameworks

For many firms, hybrid models work well. For example, a thesis-forward homepage paired with a platform-forward navigation bar, or a platform-forward main site supplemented by product-specific microsites.

What matters most is that the structure supports, rather than complicates, the story. An allocator, advisor, or investor should understand where to go and what matters within moments.

Closing Thought

A real estate manager’s website is a structural expression of the brand. The right architecture helps users grasp the strategy’s intent, the platform’s capabilities, and the path to deeper engagement. The wrong one adds friction before the strategy is ever considered.

By choosing a design model aligned with strategy complexity and communication priorities, managers create a clearer narrative environment where their strengths can be understood quickly and responsibly.

A clearer standard is emerging in real estate. The strongest websites today share a set of qualities that communicate maturity, focus, and confidence, regardless of strategy or scale.

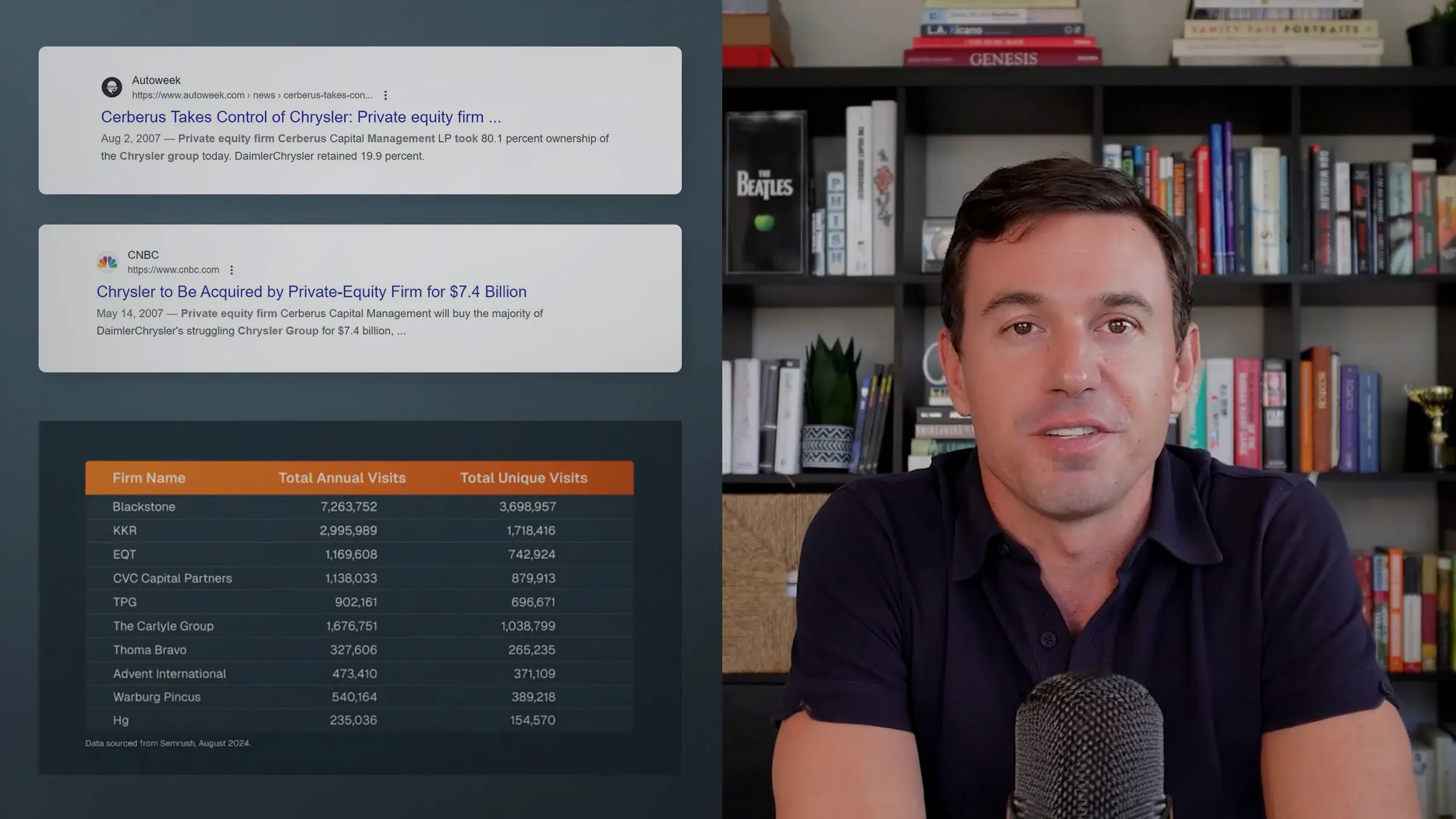

Over the past several years, real estate websites have begun shifting toward a more institutional presentation. This change is visible across a wide range of firms, from global platforms like Blackstone, Brookfield, KKR, and Carlyle to single-strategy groups and diversified investment managers. Despite substantial differences in size, structure, and geographic footprint, many of these sites now rely on similar principles that make their narratives easier to understand and more effective to navigate.

This reflects a broader shift in how modern audiences evaluate real estate platforms. For investors, advisors, consultants, and intermediaries, the website is often where early impressions take shape — impressions about strategic clarity, organizational maturity, and the firm’s ability to communicate its identity with confidence.

A site does not need to be complex to be compelling. It simply needs to help visitors understand what matters most and where to find more detail.

A few themes define this emerging standard.

1. Strategy That Becomes Clear Early

A consistent pattern across the category today is the emphasis on helping visitors understand the platform early. Many multi-strategy firms with a broad geographic reach, including groups like Blackstone, Brookfield, and KKR, now begin their digital narrative with a straightforward orientation to the overall platform before introducing more in-depth or specialized content.

These early cues help visitors interpret what they are seeing. Real estate platforms can be structurally complex. Clear framing reduces friction and makes it easier to understand how investment approaches, asset types, and markets fit together.

For example, GEM Realty Capital’s website, produced in partnership with Darien Group, clearly introduces the firm’s stance and guides visitors to deeper content at their own pace.

(See case study: https://www.dariengroup.com/cases/gem-realty-capital)

Clear strategy framing isn’t about simplifying nuance. It is about providing orientation so visitors know where they are within the story.

2. Visual Restraint That Supports the Narrative

Another notable trend is the adoption of more intentional and restrained visual systems. Unlike earlier generations of real estate websites, which often relied heavily on property galleries, many contemporary sites use imagery sparingly and with purpose.

This can include:

- architectural or structural abstraction

- selective and carefully chosen asset photography

- calm, consistent color palettes

- layouts that create visual breathing room

These choices reduce unintended signaling. A single property image can imply a specific risk profile, asset type, or geographic emphasis that may not reflect the broader platform. Visual restraint avoids this and keeps attention on the underlying strategy and team.

This shift is evident across firms of all scales. The emphasis is not on minimalism, but on clarity.

“Visual restraint isn’t about minimalism — it’s about directing attention. When imagery is used intentionally, with breathing room and consistency, the brand supports the narrative instead of competing with it. A single property photo can send unintended signals about risk or strategy, so thoughtful abstraction and selective photography help keep the focus on what truly matters: the investment logic and the team behind it.”— Anastasiia Kharytonova, Head of Design at Darien Group

3. Information Hierarchy That Supports Understanding

Information hierarchy has become one of the clearest markers of an institutional-grade website. Rather than presenting all information at once, strong websites guide visitors through a logical sequence that mirrors how institutional audiences evaluate real estate platforms.

Common traits include:

- high-level framing at the outset

- a clean transition into deeper details

- clear page-level roles

- navigation that reinforces the organization of information

Platforms with broad real estate businesses, spanning multiple vehicles, markets, or asset types, often rely on this hierarchy to make large amounts of content accessible. More specialized firms use it to communicate discipline and coherence.

Effective hierarchy signals the firm’s underlying approach to organization and communication.

4. Team Presentation That Builds Immediate Credibility

Team presentation across real estate websites has also become more consistent and structured. Visitors expect to understand who leads the platform, who drives execution, and how experience is allocated across roles.

Strong team sections typically feature:

- uniform headshot presentation

- succinct but meaningful bios

- clear articulation of roles and responsibilities

- thoughtful sequencing of seniority or function

Because operating judgment and execution discipline directly influence real estate outcomes, a well-structured team section communicates maturity without needing to state it explicitly.

5. Thoughtful Segmentation of Investment Approaches

Many real estate platforms manage multiple strategies or verticals. Websites now play a larger role in helping visitors understand these components without introducing confusion.

Diversified firms often segment their approaches by vehicle type, market orientation, or investment style. More specialized managers use segmentation to differentiate between complementary strategies within a unified platform.

Regardless of scale, thoughtful segmentation helps visitors understand how the firm is organized and how its various activities relate to one another. It clarifies not only what the platform invests in, but how its pieces fit together in practice.

A More Intentional Standard for Real Estate Websites

The rise of institutional-grade websites reflects a broader shift in how real estate firms communicate. Clear strategy framing, visual restraint, thoughtful hierarchy, strong team presentation, and intentional segmentation all contribute to digital identities that feel coherent and grounded.

These elements do not replace the depth of a meeting or a diligence review. But they make it easier for the rest of the story to land.

For firms of every scale, the opportunity is the same: a deliberate and disciplined digital presence strengthens the narrative behind the investment platform.

The hardest part of emerging manager fundraising is not the pitch meeting itself. It’s what happens after the meeting — when an LP walks out, stacks your story next to a dozen others, and has to remember two or three things about you well enough to repeat them internally. This is where narratives either survive or collapse. And most emerging manager narratives collapse because they were never designed to withstand that moment.

A Fund I or Fund II story has to do more than describe a strategy. It has to organize the LP’s memory. It has to make the GP’s worldview accessible, repeatable, and distinct enough that someone who wasn’t in the room can still understand why the idea might be worth a second look in the next cycle.

The reason so many emerging managers struggle here is structural: they think about narrative as explanation, when LPs experience it as architecture. A clear story is not a chronological recounting of your experience or a list of your differentiators. It is an organized system of ideas — origin, category, thesis, edge, proof — that stack in a way LPs intuitively understand. And when that system is well built, the downstream conversations become dramatically easier because the LP already knows how to think about you.

1. Narrative Begins With Category, Not Strategy

Emerging managers often begin their pitch with the specifics of what they do: their sourcing channels, their underwriting criteria, their sector knowledge, their deal lens. But LPs are not ready for that level of detail until they have a mental model of the category you operate in.

Narrative starts one layer up: What market are you playing in, and why does it make sense?

Most EMs underestimate how little LPs know about the nuances of sub-strategies, niche asset classes, or operational dynamics. If you don’t define the category clearly, the LP will place you into whatever adjacent bucket feels most familiar. And once the LP categorizes you incorrectly, it is extraordinarily difficult to pull the narrative back.

A good emerging manager narrative establishes the category in one or two sentences — simple enough that a non-expert could repeat it, specific enough that it doesn’t collapse into something generic. Only then does strategy begin to make sense.

2. The Strategy Must Emerge Naturally From the Category

Once the category is clear, the strategy has to feel like the obvious response to the underlying market structure. Emerging managers often give LPs a strategy that feels theoretically interesting but disconnected from the opportunity they just described. The jump is too big. The linkage is missing.

LPs respond most strongly to strategies that feel structurally inevitable — where the GP’s approach reads as the logical answer to the problem the category presents. When the strategy grows naturally out of the category, the LP not only understands what you do; they understand why you do it.

Narrative is persuasion through architecture. When the staircase is built correctly, the LP moves up it without noticing.

3. The Edge Must Be Singular, Not a Catalog

Most emerging managers have an instinct to list every possible advantage: sourcing network, operating experience, market insight, proprietary pipeline, a differentiated take on value creation. But lists do not create memory. They create blur. LPs retain one thing. Maybe two. Never five.

A strong narrative surfaces one primary edge — the thing that truly makes the manager distinct — and supports it with secondary ideas that reinforce the same conclusion. When the edge is singular and well chosen, everything else becomes supporting architecture instead of narrative clutter.

The strongest emerging manager edges are usually:

- behavioral (how they think or operate),

- structural (where they sit in the market), or

- experiential (what they understand more deeply than peers).

The edge is not a feature; it is a worldview. If it cannot be expressed cleanly, it will not survive LP translation.

4. Proof Must Be Narrative, Not Decoration

Emerging managers often misunderstand what “proof” means in early fundraising. Without formal attribution, many EMs treat their past deals as cosmetic reinforcement — color, context, background. But LPs don’t experience proof as biography; they experience it as evidence that the GP thinks clearly and acts consistently.

The past matters when it supports the narrative spine. A deal example is not meant to show that you were involved in something impressive. It is meant to demonstrate that the edge you’ve claimed actually manifested in the real world. The deal should feel inevitable in retrospect, as if the GP could not have acted differently.

When proof is narrative, not decoration, LPs internalize it as part of the story rather than trivia.

5. The Test of a Good Narrative Is Portability, Not Eloquence

Managers often assume that if they explain their strategy elegantly, they’ve succeeded. But most LPs do not make decisions in isolation. Their colleagues, committees, and consultants become part of the narrative chain. If the story dies in translation, the strategy dies with it.

The real test of narrative is whether someone who has only heard it once can still explain:

- the category

- the approach

- and the edge

without losing the thread.

In practice, this means emerging manager narratives must sacrifice eloquence in service of durability. A narrative that sounds refined in the room but collapses later is less effective than one that feels simple in the moment but survives for months.

Narrative durability is a design choice.

Closing Thought

Emerging managers often think their challenge is storytelling. In reality, it is structure. LPs remember what the narrative architecture makes memorable. A coherent category, an inevitable strategy, a singular edge, and proof that reinforces the thesis — those are the bones of a story that lasts.

You cannot control when an LP moves. But you can control whether your story is still intact when they think about you again in three years. That, more than anything, is the difference between a Fund I narrative that dissipates and one that compounds.

Emerging managers tend to think LPs will evaluate them along a familiar axis: strategy quality, pedigree, relevant experience, and whatever informal track record they can reasonably claim. Those elements matter, but they are rarely decisive early on. In the first handful of meetings, LPs are not ranking your strategy against other strategies. They are trying to decide whether you are investable at all. And that is a different psychological test than most emerging managers expect.

What LPs actually look for first is not upside; it’s readiness. Before they can form a view on whether your strategy is compelling, they need to believe that you are far enough along in your institutional story to justify taking the next step. A Fund I or Fund II allocation is not just an underwriting decision — it is an early judgment about organizational maturity, narrative discipline, and whether the GP understands the rules of institutional capital formation. Those judgments form in minutes, not months, and they often crystallize well before your strategy discussion is even over.

Across a decade of working with emerging managers, I’ve learned that LP expectations fall into three categories: coherence, credibility, and compression. If a manager clears those bars early, the rest of the conversation becomes meaningfully easier. If they don’t, even a sophisticated strategy will struggle to land because the LP has not yet resolved the more fundamental question of whether the GP is institutionally “real.”

1. Coherence: LPs Need a Story They Can Repeat Accurately

LPs do not retain detail the way managers think they do. They are exposed to too many first-time funds, too many repeat funds, too many strategies that rhyme with one another. In that environment, coherence is not just a virtue — it is a survival mechanism. LPs need to be able to summarize you later, often to someone who wasn’t in the meeting. And if your story doesn’t translate cleanly outside the room, it tends not to matter how strong your ideas are inside it.

Coherence, in practice, means you can explain who you are and what you do in a language LPs already understand. A clear category. A defined strategy. A narrow, believable edge. Too many emerging managers default to subtlety, hoping nuance will communicate sophistication. In reality, it creates fog. If an LP cannot describe your strategy in two or three sentences, the probability that they will return for a second meeting drops sharply — not because they don’t like you, but because they can’t remember you.

LPs don’t need perfection. They need portability. That is the quiet test emerging managers don’t realize they’re being graded on.

2. Credibility: LPs Need to Believe You Are “Institutionally Ready”

Credibility is not the same as experience. LPs routinely meet managers who have impressive backgrounds, sharp intellects, and rich histories of exposure to complex transactions. But credibility requires a different kind of signal: the sense that the manager can run a disciplined investment process, communicate clearly, withstand scrutiny, respond to surprises, and behave like a fiduciary.

This is why brand and narrative matter so much more than emerging managers expect. LPs cannot see your underwriting process. They cannot see your deal judgment in real time. They cannot see how you behave under pressure. What they can see is whether your materials are organized, whether your website reflects thoughtfulness instead of chaos, whether your messaging is stable, and whether the way you talk about your own strategy aligns with how a professional investor would evaluate it.

No LP will ever say, “Your deck looks sloppy, so we assume your underwriting is sloppy,” but that inference happens constantly. LPs look for disqualifiers early: unfocused strategy language, mismatched design choices, a narrative built entirely around pedigree, or a website that feels like a developer’s landing page instead of an investment firm. These friction points are not fatal individually, but collectively they form an impression that the manager is not quite ready for institutional capital.

Credibility is quiet. It’s not something you can boast about; it’s something you signal through the quality of decisions you’ve already made.

3. Compression: LPs Need You to Get to the Point Faster Than You Think

If there is a single universal friction point for emerging managers, it is their tendency to overexplain. When you’re early in your story, everything feels important. Every deal, every operating insight, every nuance of your sourcing advantage feels like it must be included. But LPs do not grant unlimited attention. They decide quickly whether the essence of your strategy is understandable, durable, and aligned with their mandate.

Compression is a discipline. It forces emerging managers to decide what matters most and discard what only matters to them. When I was raising for BKM Capital Partners in 2014, it took too many slides to explain the multitenant industrial thesis. We eventually sharpened it, but the early version buried the most important point under a mountain of detail. Only later did I realize how common this problem is. Emerging managers regularly bury their own lead, often because they’ve never been forced to articulate the one or two ideas that truly define their strategy.

LPs form early impressions on the basis of clarity, not volume. When a manager can express their strategy in a way that feels simple without being simplistic, LPs lean in. When a manager requires fifteen minutes of backstory to land their point, LPs start filtering out.

Closing Thought

Before LPs learn to like you, they need to understand you. Before they can understand you, they need to believe you are prepared. And before they believe you are prepared, they need to see a story that makes sense on its own terms — one that is coherent, credible, and compressed enough to survive outside the room.

Emerging managers often think fundraising is a referendum on their strategy. In practice, it is a referendum on their clarity. Strategy becomes persuasive only after the LP decides the manager is institutionally real, and clarity is the shortest path to that judgment.

1. The Legitimacy Gap: The Real Problem Emerging Managers Face

After working with hundreds of emerging managers across private equity, real estate, credit, and niche alternatives, you start to notice the real patterns — not the optimistic conference panels, but the structural truths shaping Fund I, Fund II, and Fund III trajectories. “Emerging manager” is a broad term, but what unifies this group isn’t AUM or asset class. It’s that they are early in their institutional story, and LPs can usually tell immediately.

The obstacle is the legitimacy gap — the distance between how a manager sees themselves and how an LP perceives their readiness. Strategy, pedigree, and track record matter, but legitimacy is the threshold condition that determines whether anyone will take the next step. In plain terms: Darien Group helps emerging managers close the legitimacy gap faster than they could on their own.

2. The Nonlinear Reality of Early Fundraising

Most emerging managers understand conceptually that fundraising will be hard, but many still assume it will follow some recognizable pipeline. In reality, Fund I and Fund II almost never move in straight lines.

When I worked at BKM Capital Partners during their first fundraise, the expectation was that friends and family would anchor $25–50 million. They didn’t. The turning point came from a single Scandinavian LP who happened to be in Los Angeles for one day. We were taking twenty meetings a week; that one meeting changed the trajectory.

You do not know which meeting matters — and you cannot engineer the sequence.

What you control is your consistency. Everything else is unpredictable.

3. LPs Often Don’t Understand Your Category — And You Must Bridge That Gap

Another structural reality is that LPs often don’t understand a category nearly as well as the GP assumes. At BKM in 2014, multi-tenant industrial was seen as non-institutional: too small, too operational. Five years later, it was a multi-billion-dollar institutional staple.

Much of that gap was closed through education. Brian Malliet produced extensive collateral not because he liked marketing, but because emerging managers often have to demonstrate that the category itself deserves institutional attention. Today’s emerging managers know they need a website and a pitchbook, but they still underestimate how much education is required — and how high the bar has become.

4. Why Some Emerging Managers Break Through — and Most Don’t

The managers who eventually succeed distinguish themselves in ways that have little to do with polish or charisma. They stay consistent when the market is slow to respond. They specialize instead of drifting toward generalist territory. And they choose strategies the market actually wants.

You cannot brand or design your way out of a weak thesis. You cannot out-pedigree an established incumbent. But if you are the sharpest expression of a category the market is curious about — and you communicate that clearly — you will eventually find the LPs who recognize it.

Consistency and specialization beat cleverness and pedigree.

This is a quiet truth people don’t say out loud, but it is one of the defining characteristics of the managers who make it.

5. The 10-Year Journey: How LPs Actually Form Memory

The “10-year journey” is not a motivational slogan. It is the psychological structure of emerging manager fundraising. Nearly every Fund I manager hears: “We like it — come back for Fund II.” It isn’t always dismissal. LPs can only allocate to a small set of new managers each cycle; the rest are catalogued for later.

Here is the rough math:

- Most early meetings won’t produce capital.

- A minority will matter years later.

- The decisive ones often surface unexpectedly.

LPs remember only two or three things about you. Those things must be durable enough to make sense when they see you again in three years.

6. LPs Look for Disqualifiers First—Often Before They Look for Strengths

Emerging managers tend to assume LPs are evaluating them with optimism. In reality, LPs begin in filtering mode. Whether the LP is a CIO at a major institution or a sophisticated family office, they make early judgments based on coherence, clarity, and organization.

Common disqualifiers include:

- sloppy, outdated, or overdesigned materials

- messaging built entirely on pedigree

- jargon without a point of view

- broker-like or developer-like websites

- lack of clear specialization

- strategy drift or narrative drift

LPs evaluate operational discipline through brand and materials. If your deck is disorganized, they assume your underwriting is disorganized. These judgments form much earlier than most emerging managers imagine.

7. What Institutional Legitimacy Actually Looks Like at the Beginning

Legitimacy at Fund I or Fund II isn’t about appearing large; it’s about appearing ready. A coherent brand, a credible website, a pitchbook that withstands scrutiny, sober expectations, and a strategy distilled into a few memorable ideas go much further than managers expect.

If you are young in “fund years,” your brand has to do a little extra work to signal maturity. This isn’t pretense — it’s optics, and LPs react to it immediately.

8. The True Purpose of a Fund I Pitchbook

Most emerging managers misunderstand this. A Fund I pitchbook is not theatrical persuasion. It has two practical responsibilities:

- Establish the category — especially if it is new, evolving, or misunderstood.

- Establish your ownership of it — why your angle is sharper or more structurally advantaged.

Even in HNW settings, the deck is usually forwarded internally. It must be designed to withstand that level of scrutiny.

9. The Mindset Shift from Syndications to Funds

Transitioning from deal-by-deal work to fund management requires a different time horizon. Syndications reward episodic success; funds reward sustained progress. Many syndicators attempting Fund I never close it — not because they lack talent, but because the strategy doesn’t scale or they lose momentum before the flywheel turns.

In many cases, Year 1 is quiet; Year 2 is where traction appears. Fund I is not the destination. It is Chapter One in a multi-fund arc.

10. What Darien Group Actually Does for Emerging Managers

We are not here to make an emerging manager look like a billion-dollar platform. Nor are we here to gloss over weak strategies. Our role is to help managers articulate a coherent, durable narrative; sharpen their point of view; build materials that won’t age poorly; and find the intersection between professionalism and personality.

Or, said more bluntly:

We help emerging managers close the legitimacy gap faster, so they can spend more of their energy actually building the track record that will carry them forward.

11. The Fundamentals Haven’t Changed — But the Bar Has

Capital raising has changed more in the last four years than in the previous decade. Expectations are higher. LPs filter faster. But the fundamentals remain constant: a coherent category, a compelling strategy, a durable story, and consistency over time. Emerging managers can’t control how long momentum takes to form, but they can control the clarity and maturity of the story they tell.

Everything else sits downstream of legitimacy.