.jpg)

Side Letters

Side Letters is a collection of essays, research, and analysis on how investment firms communicate with investors, management teams, and transaction partners. The focus is practical: how firms articulate value, build credibility, and navigate increasingly complex evaluation environments.

Featured Videos

Secondary investing is one of the rare corners of private markets where the strategy’s sophistication is both its strength and its communication barrier. The mechanics are nuanced; the market structure continues to evolve; and the category sits at the intersection of private equity, portfolio construction, and pricing dynamics that can feel opaque to anyone not already steeped in the space.

Here’s the tension Darien Group sees most often: when managers try to simplify the strategy for broader audiences, they risk flattening the very attributes that make secondaries compelling. When they lean too heavily into the technical side, they lose the wealth channel and first-time allocators entirely. Neither outcome serves the category.

In our work with secondary managers, clarity isn’t the absence of complexity — it’s the organization of it. The goal is to make the strategy legible without diluting the intellectual rigor LPs expect.

Why Secondaries Feel Harder to Explain Than Other Private Markets Strategies

Most private market strategies begin with an intuitive idea: acquiring companies, lending capital, developing properties, delivering yield. Secondaries begin with something abstract — a market for existing fund positions — and require audiences to understand:

- the life cycle of a private equity fund,

- how NAVs are marked,

- why sellers transact,

- how pricing reflects future expectations, where visibility is higher.

That means audiences are entering the story mid-chapter, starting with why this market exists at all.

The Three-Layer Framework for Explaining a Complex Strategy

The most effective secondary firms use a narrative architecture that moves from concept → mechanics → application. This sequence anchors the reader before introducing nuance.

Here's the structure we often build:

When these layers are collapsed into one paragraph audiences walk away with partial comprehension and no conviction.

Layer 1: Establish the Concept Without Using Jargon as a Shortcut

At this stage, the audience doesn’t yet need to understand GP-leds, LP-leds, structured solutions, or price-to-NAV dynamics. They need to understand:

- the secondary market exists to transfer fund interests,

- buyers gain exposure to companies further along in their value-creation arcs,

- transactions typically occur at more mature stages of the investment lifecycle.

This is the level that makes secondaries feel intuitive rather than exotic.

An early conceptual table can often replace two pages of text:

This table is scaffolding the audience so later complexity has somewhere to land.

Layer 2: Clarify the Mechanics With Enough Detail to Build Trust

This is the portion that historically gets muddled. Some firms use too much jargon; others avoid it entirely. The goal is precision without overload.

The mechanics that matter most in secondary communication:

- How portfolio visibility informs underwriting

- How pricing reflects the maturity of underlying companies

- How diversification (vintage, sector, manager) shapes risk-adjusted return

- The difference between GP-led and LP-led transactions — at the highest level

- How cash flows behave (earlier yield, smoother return profile)

Layer 3: Show Application Where Clarity Becomes Differentiation

Once the audience understands what secondaries are and how they work, the final question becomes: why does this manager’s approach matter?

This is where specificity builds trust:

- What types of sellers are most relevant to your sourcing approach?

- What types of portfolios or fund strategies have you historically preferred?

- How do you think about concentration, pacing, and exposure limits?

- How consistent is your strategy across cycles?

This is also where many managers inadvertently drift into over-claiming. It’s better to be specific than sweeping.

A simple framework often helps anchor differentiation:

The discipline here is resisting the urge to say everything. Clarity is selective by definition.

Why Oversimplification Is the Greatest Risk in Secondaries Messaging

When a firm reduces the strategy to “J-curve mitigation and diversification,” they accidentally position themselves as interchangeable with the entire category and the category is expanding. Advisors are learning. Platforms are adding new structures. Individual investors are becoming a meaningful audience. LPs are applying sharper differentiation filters.

This is why structured complexity is the real advantage.

Closing Thought

The secondary market is dynamic; it should sound dynamic. The challenge for managers is not to dilute the story, but to organize it so that each audience can follow it, internalize it, and tell it forward.

A legible secondary story does three things:

- Shows the category is understandable

- Shows the strategy is repeatable

- Shows the manager is disciplined

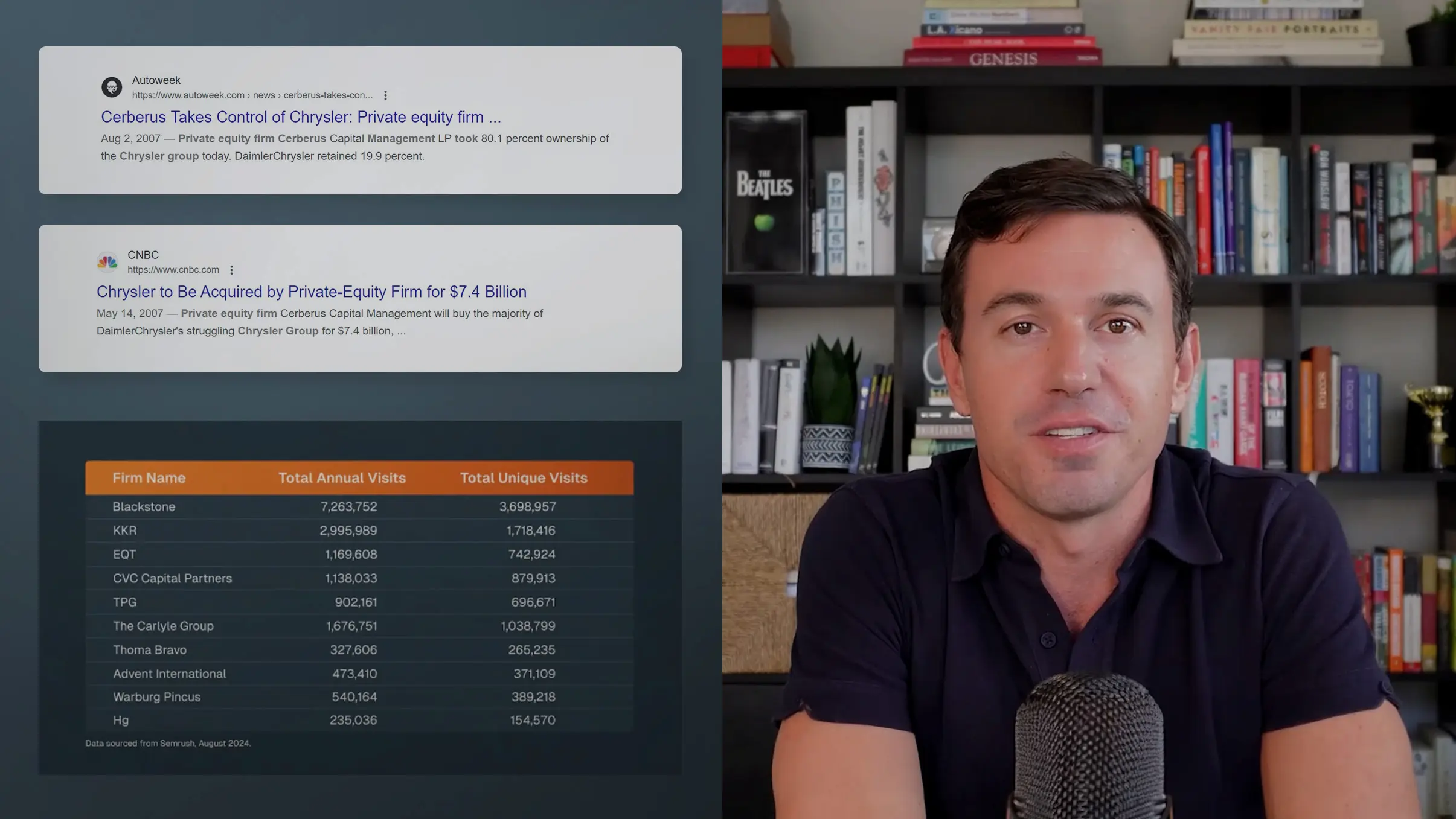

Spend enough time reviewing real estate pitchbooks and you start to see a consistent pattern: there are only two categories. Decks that look and feel institutional, and decks that don’t. And the divide has very little to do with design vocabulary or stylistic preference. It’s about the signals that design quality sends to an audience that reviews hundreds of these materials each year.

Institutional LPs don’t use the language of designers. They don’t talk about kerning or color theory. But they are exceptionally quick at making judgments about professionalism, discipline, and operational maturity. In a pitchbook, design is rarely the story — but it is always part of the psychology.

This creates a strange dynamic in real estate, a category where many managers come from operator or development backgrounds rather than allocator backgrounds. They may be excellent investors, but design is not a natural skill set. And when the pitchbook looks like a 10-year-old template or something assembled by whoever “knows PowerPoint,” LPs draw conclusions far beyond the aesthetic.

Below is a candid look at the design standards that actually matter to institutional LPs, why they matter, and how managers can present themselves with the level of polish investors instinctively expect.

Professional vs. Amateur: LPs Know the Difference Instantly

Most managers underestimate how quickly an LP can tell whether a deck was built professionally. They don’t need to identify the font or critique the color palette; they can simply feel whether the materials look and behave like institutional tools.

The most common red flag is not outdated taste — it’s dated templates. Slides that look like they came from a 2012 PowerPoint file. Generic gradients. Clipart-level icons. Mismatched shapes and colors. Charts pasted in from Excel without any reformatting. Image crops that are slightly off. A deck that looks “stitched together.”

These details may seem trivial, but they accumulate into a very clear impression:

If the manager didn’t invest in presenting their strategy cleanly, where else have they underinvested?

This reaction is not fair in every instance, but it is extremely common.

The good news is that professional design is not difficult or expensive to access. A manager doesn’t need a six-figure agency to create an institutional-grade pitchbook. They simply need someone — internal or external — who understands how to produce clean, modern slides. Someone who knows how to apply basic discipline. Someone who understands that design communicates far more than style.

Institutional Design Isn’t Ornate — It’s Clean

There is a misconception that institutional design means decorative design. In reality, institutional LPs respond to simplicity, not flair.

A premium, mature deck usually has the following characteristics:

- Clean slides with clear hierarchy.

Not walls of text, not ornamental shapes. - Charts that match the visual brand.

Not screenshots from other documents, not mismatched fonts. - Photography that is strong (or intentionally omitted).

Real estate is visual, but bad visuals hurt more than no visuals. - Consistency across slides.

Colors, spacing, image treatments, and layouts should feel coherent.

None of this requires a designer with an MFA. It requires good judgment and discipline. LPs are not looking for beauty — they are looking for maturity.

Photography: A Differentiator When Used Well, a Liability When It Isn’t

Real estate has an inherent advantage over private equity: the asset class is tangible. If the assets photograph well, photography is one of the fastest ways to build connection and credibility.

But this only works when the assets support the story. If the properties are tired, dated, or visually unappealing, showing them hurts more than it helps. Many managers underestimate this dynamic. They assume “showing the real thing” always wins. It doesn’t. LPs form impressions quickly, and mediocre imagery creates subconscious skepticism.

When the assets are strong, show them proudly. When they’re not, build a more abstract visual identity. This is one of the most important judgment calls in real estate materials — and one of the most overlooked.

Design Signals Something Deeper: Discipline

Pitchbooks do not need to be visually innovative. But they do need to be visually disciplined. Discipline is the underlying signal LPs are responding to. Clean decks imply clean thinking. Consistency suggests operational maturity. A professional visual system suggests a manager who is organized, structured, and attentive.

Messy design sends the opposite signal. LPs wonder:

- If the materials look disorganized, what does the underwriting process look like?

- If the visuals are sloppy, how tight is the property management discipline?

- If the pitchbook feels like a patchwork, what does this say about reporting?

None of these implications are necessarily accurate, but LPs make quick, subconscious leaps. In real estate especially — where operator competence is paramount — the leap is hard to avoid.

Avoid the “Broker Memo” Aesthetic at All Costs

Real estate operators often communicate using the same artifacts they use internally: deal memos, OM packets, broker marketing summaries, zoning diagrams, floor plans, maps with arrows. These materials serve a purpose inside the real estate ecosystem, but they are disastrous in fundraising.

Broker memos are dense, cluttered, and unfriendly to non-operators. They assume familiarity with local markets and deal mechanics. They make sense to someone who spends their days touring properties—not someone trying to evaluate an investment strategy across dozens of managers.

When a pitchbook resembles a broker packet, LPs silently categorize the manager as unsophisticated or underprepared. Even if the underlying strategy is compelling, the materials undermine it.

Pitchbooks must be decks, not OMs. They must feel investable, not transactional.

“Institutional Design” Does Not Require Design Vocabulary

Real estate managers sometimes worry they don’t have an eye for design, and they often don’t have a designer in-house. That’s fine. LPs are not grading aesthetic nuance—they’re grading whether the materials feel professional.

Institutional design is not:

- ornate,

- flashy,

- hyper-stylized, or

- filled with dramatic typography.

Institutional design is:

- clean,

- consistent,

- modern,

- unforced.

It is the absence of distraction.

It is the presence of coherence.

A pitchbook that feels effortless is usually the product of someone who knew what to remove, not what to add.

Use Design to Support Skimmability

LPs skim — sometimes aggressively. Good design helps them do this without missing the thread.

A skimmable pitchbook uses:

- clear, thesis-driven headlines,

- visual breathing room,

- layouts that reveal the point quickly,

- and slides that can be understood in a few seconds.

Bad design works against skimming. The eye doesn’t know where to go. Key points get buried. The hierarchy collapses. When LPs skim a messy deck, they lose the narrative — not because the story wasn’t good, but because the design didn’t help them find it.

Skimmability is not just about writing. It is about design that respects how people actually read.

Design Doesn’t Win the Mandate — But It Can Lose It

No LP commits to a fund because the pitchbook is beautiful. But LPs do walk away from managers whose materials feel amateurish or inconsistent. They don’t always say it directly, but you feel it in the lack of follow-up, the muted enthusiasm, or the subtle shift from curiosity to polite disengagement.

Design does not create conviction.

But it does create permission for conviction.

A good deck opens the door wide. A sloppy deck makes the LP second-guess whether they should step through it.

Secondary investing has always carried a messaging complexity. Even among seasoned LPs, the mechanics, pricing logic, and portfolio-construction benefits aren’t as widely internalized as many managers assume. As more secondaries firms expand beyond the traditional institutional base — into wealth channels, intermediary platforms, and newly PE-curious individual investors — the communication burden has multiplied.

In these environments, clarity isn’t about “simplifying” the strategy. It’s about developing a clear narrative system that meets each audience where they are without diluting the intellectual integrity of the category. This is one of the biggest shifts I’ve seen in our work with secondary managers: firms are no longer just articulating what they do; they are architecting explanations that scale across very different levels of financial fluency.

Why Audience Segmentation Matters More in Secondaries Than Most Managers Realize

Multiple types of investors approach secondaries with entirely different mental models. Some anchor on diversification. Some on the J-curve. Some on liquidity, cash yield, downside protection, or the ability to buy into high-quality portfolios at attractive pricing.

In other words: the audience isn’t monolithic, and neither should the narrative be.

Here’s a simplified illustration we often use in early strategy sessions:

A sophisticated investor might want to know how GP-led and LP-led exposures balance across a portfolio; an individual investor might need to understand what a private equity fund is in the first place. If those two explanations are written in the same paragraph, both audiences lose.

Institutions: Reinforcing Selectivity, Process, and Repeatability

Institutional LPs understand private equity. They understand fund cycles, pricing dynamics, and market structure. Yet secondaries still require more explicit communication than many managers expect.

The reason is subtle: institutions know what secondaries are, but they don’t always know how you do them.

For this group, the narrative must quickly clarify:

- How you source opportunities (without over-indexing on volume)

- What selectivity means in practice

- What your underwriting prioritizes at the asset and fund level

- How your portfolio construction has remained consistent across cycles

One institutional LP told a client of ours during discovery: “I just need to know why your process is reliable in every market environment.” That distinction is important. This is where detailed but digestible frameworks — process diagrams, funnel snapshots, exposure maps — do more work than copy alone.

Advisors and RIAs: The Middle Layer With the A High Communication Burden

Advisors sit in a unique place: they are financially sophisticated, but they are not typically secondaries specialists. They need messaging that answers both “What is it?” and “How do I use it?”

Three principles matter most here:

1. Give advisors language they can use with their clients.

If an RIA cannot confidently repeat your explanation to a client, the strategy won’t scale in the wealth channel.

2. Clarify the role of secondaries in a portfolio.

Anchor on relatable frameworks:

- dampening the J-curve,

- smoothing deployment,

- diversification by vintage and strategy,

- earlier cash yield characteristics.

3. Use structured, modular educational content.

We’ve seen firms succeed with a “Core Concepts” section that breaks down fundamentals in 250–300-word modules — enough to be substantive, not so much that it overwhelms.

Check out Pomona Capital's Insights & Education page. Here, the firm takes the opportunity to answer "What is a secondary?" and "Why invest?" With a page like this, Pomona becomes a source of truth and an educational resource for advisors and prospective investors.

Individual Investors: Beginning the Narrative Earlier Than You Think

For individual investors, especially those accessing private markets for the first time through feeder structures or interval funds, the starting point is not the intricacies of secondaries. It’s understanding private equity itself.

This group needs clarity on:

- How private equity works

- Why companies choose PE capital

- What a fund is

- How primary PE investing differs from secondaries

- Risk framing and liquidity expectations

A table like the one below often accelerates comprehension:

The job of the narrative is not to “sell.” It’s to orient.

Closing Thought

The firms that outperform in communication aren’t the ones who simplify the most. They’re the ones who structure the story so each audience can enter at the right level — and graduate into deeper material as their fluency grows.

A well-architected secondaries narrative has three characteristics:

- Accessible without being reductive

- Scalable across audiences without fragmenting the brand

- Sophisticated enough to build conviction among institutions

When these three conditions are met, firms expand their reach to audiences who may not otherwise engage. A strong secondary strategy may generate returns, but a clear secondary narrative generates momentum.

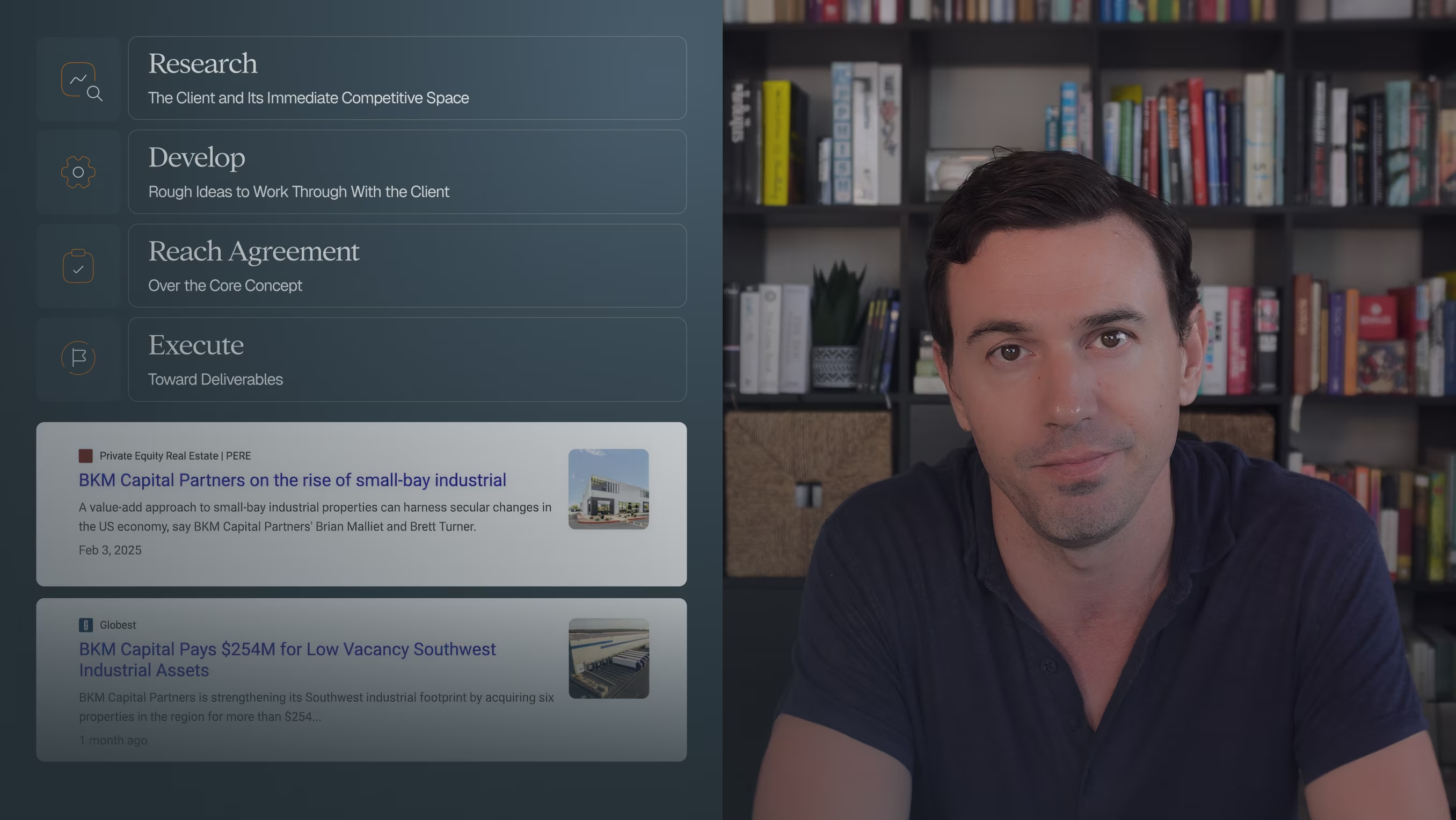

How origin, belief system, and right-to-win sharpen a firm’s first impression

Emerging managers often spend the early months of firm building refining the mechanics: forming an entity, assembling the team, modeling the fund, and building the deck. What doesn't always get actively addressed is the narrative foundation that helps LPs understand why this firm, why now, and why this team is structurally advantaged in its chosen corner of the market.

Across DG’s work with first-time funds or emerging managers, we see one consistent pattern: a clear, three-act story accelerates comprehension, shortens meeting cycles, creates a more consistent experience across all materials, and builds a strong foundation for the future trajectory of the firm.

What follows is a repeatable structure that is simple enough to be memorable and sophisticated enough to hold institutional scrutiny.

Act I: The Origin Story — The Inflection Point That Made the Firm Inevitable

Nearly every new manager has a “why we left” moment, but not every manager turns that into a crisp positioning asset. The strongest origin narratives don’t recount one person’s career chronology; they identify the inflection point that made the firm necessary.

A useful framing question: What did we observe — about the market, the model, the culture, or the customers — that made doing things the conventional way no longer make sense?

A client of ours once put it simply: “We weren’t starting a firm — we were responding to a gap we couldn’t unsee.” That framing signals intentionality, clarity of purpose, and a level of self-awareness that LPs consistently respond to.

Components of a Compelling Origin

The goal is coherence. Investors want to see that the firm’s creation is the logical next step.

Act II: The Belief System — The Principles That Drive Judgment

Across emerging manager messaging, belief systems are often implied but rarely articulated. When left unsaid, they force LPs to connect the dots themselves; when stated clearly, they become a stabilizing force across the entire deck and diligence process.

This is where emerging managers have an advantage. Unlike large platforms with extensive histories and deep-rooted philosophies, a first-time fund can anchor itself around a few precise convictions that directly shape its process. A true belief system should be observable in how a team sources, evaluates, makes decisions, and engages with others.

A Belief System That Signals Investment Discipline

When belief systems are well-framed, they create a throughline from origin to strategy. They also give LPs a reference point for evaluating how a team will behave when decisions are ambiguous.

Act III: The Right-to-Win — The Firm’s Unique Combination of Strengths

This is the most scrutinized part of the story, and often the least developed. Many emerging managers default to what sounds differentiating — sector depth, relationship networks, operating experience — but few offer a clear view into why the intersection of those capabilities matters.

What sets strong Fund I narratives apart is their ability to articulate the combined advantage, or the idea that the firm’s strength isn’t any single competency, but the interaction among them. LPs respond not just to the ingredients, but to the way they function together to create repeatability.

A client once noted, “Our edge isn’t that we do one thing exceptionally — it’s that the way we put our strengths to work creates outcomes others don’t naturally reach.” That framing can shift the discussion from table-stakes functions to integrated capabilities.

A Simple Framework for Defining Right-to-Win

By defining the firm’s right-to-win through the interaction of capabilities, emerging managers avoid generic positioning and help LPs understand the specific environments in which the team is most effective.

The Result: Bringing the Three Acts Into Materials

Once the core narrative is developed, the next task is to translate it across all materials. At this stage, the goal is to ensure its logic is legible across every brand touchpoint.

A clear three-act structure strengthens:

- The deck, by giving each section a defined purpose

- The website, by establishing clear positioning and intuitive flow

- The sourcing narrative, by helping founders understand the firm’s intent

- LP meetings, by anchoring conversations in shared language

- Early team alignment, by creating internal consistency

Where the Three Acts Live in a Fund I Deck

For emerging managers, clarity is a key competitive advantage that can define the success of early funds.

Conclusion: Fund I Is a Story of Intent, Not Scale

The most effective first-time managers don’t position themselves as miniature versions of larger funds. They articulate a story grounded in intention, including why they formed, how they think, and where they meaningfully outperform.

That story, when built deliberately, becomes the connective tissue between a manager’s experience, strategy, and eventual track record. It ensures that when LPs evaluate the opportunity, they’re hearing the narrative in a structure that clicks immediately.

How founders demonstrate mastery of their mandate and accelerate trust long before Fund I capital is deployed

Emerging managers face a unique asymmetry at launch: the founding partner and team often have years of relevant experience, but the firm itself has no attributable track record. LPs understand that dynamic, but they still need to calibrate whether the founder has a sufficiently sharp point of view, an ability to articulate it, and a disciplined method for applying it.

This is where thought leadership becomes more than a marketing tool. It becomes a way for the founder to demonstrate mastery of the investment mandate, reveal their worldview, and build confidence in their ability to lead a focused, repeatable strategy.

For Fund I platforms, where the founder is the firm’s core intellectual asset, thought leadership demonstrates a unique point of view and a skill set to capitalize on the opportunity.

1. Thought Leadership Helps Founders Show Their Framework, Not Just Their Background

Founders often carry rich institutional histories, including sourcing patterns, exposure to complex deals, board roles, cross-functional leadership, and thematic research. However, if these experiences remain implicit, LPs are left guessing how they translate into the new strategy.

Thought leadership enables the founder to define:

- How they interpret the space

- How they evaluate opportunities within a specific mandate

- What convictions guide their decision-making

- What constraints they take seriously

How Founders Turn Experience Into Demonstrated Judgment

Thought leadership converts experience into something observable, transferable, and evaluable.

2. It Helps Founders Define and Substantiate the Mandate

When a founder enters the market with a new fund, the mandate must feel both deliberate and earned. Thought leadership creates the intellectual scaffolding behind that mandate:

- Why this sector, not adjacent ones

- Why this stage of company maturity

- Why the strategy is sufficiently differentiated

- Why the opportunity exists now

- Why the founder is well suited to pursue it

Without this articulation, LPs may perceive Fund I strategies as broad, flexible, or reactive. With it, the mandate becomes a product of focused, accumulated insight. A well-articulated mandate becomes a core differentiator for the emerging manager.

3. It Allows the Founder’s Voice to Become a Strategic Asset

In emerging platforms, the founder’s voice is the brand. It shapes how LPs understand the strategy, how founders perceive partnership, and how the market categorizes the firm among its peers.

Thought leadership helps the founder build a recognizable and ownable voice by:

- Clarifying tone (measured, analytical, grounded)

- Establishing the firm’s problem-solving posture

- Demonstrating a consistent worldview

- Showing how the founder communicates under uncertainty

- Reassuring LPs that the firm has depth beyond marketing language

This is especially valuable before the first deal, the first board seat, or the first portfolio milestone. The founder’s thinking is the earliest proof of capability.

4. It Speeds Trust Building in a Way Pitch Decks Cannot

Decks show structure. Thought leadership shows substance. Decks show strategy. Thought leadership shows judgment. Decks show the plan. Thought leadership shows how the founder will behave when the plan gets tested.

Stakeholders, including LPs, founders, management teams, talent, and intermediaries, increasingly use published perspectives as a filter:

- Does this founder seek nuance or settle for conventional views?

- Do they demonstrate sector fluency without overconfidence?

- Do they articulate risk realistically?

- Do they reveal how they form conviction?

This is trust-building at scale, before a single meeting is held.

5. It Strengthens Internal Alignment

Publishing forces clarity. It compels the founder to:

- Make implicit beliefs explicit

- Prioritize what the firm actually stands for

- Establish decision-making principles

- Create intellectual guardrails for the team

For small teams, this alignment is invaluable. It increases consistency in sourcing, underwriting, portfolio support, and LP communication.

6. It Creates Early Proof Points — Appropriate for Stage, Authentic to the Firm

Emerging managers should avoid overextending their thought leadership into predictions, claims of proprietary insight, or overly technical analysis. Instead, the strongest content demonstrates:

- Clear market observation

- Practical operator empathy

- Pattern recognition earned over time

- Strategic boundaries

- Realistic assessments of where the firm can uniquely contribute

Founder Thought Leadership That Signals Mastery (Without Overclaiming)

These pieces function as early indicators of how the founder will behave when real capital is at work.

Conclusion: Thought Leadership Is Not About Visibility — It’s About Demonstrated Mastery

Thought leadership for emerging managers is about demonstrating mastery and "right-to-win." The founder’s thinking is the firm’s first real asset. Thought leadership allows that thinking to be seen, evaluated, and understood.

It accelerates credibility by:

- Revealing how the founder interprets the world

- Demonstrating mastery of the mandate

- Establishing a clear and consistent voice

- Building trust with LPs and operators

- Creating internal alignment

- Providing early proof points appropriate for a Fund I platform

Done well, thought leadership amplifies the founder’s judgment and the firm's reason for being.

Real estate investment manager websites are doing more work than they used to. By 2026, they are no longer just digital brochures or portfolio showcases. They are reference points for LPs, lenders, operating partners, sellers, and recruits — often reviewed before a conversation ever takes place and sometimes without context.

This checklist reflects how real estate manager websites are actually being used today, and what they need to do to support credibility, clarity, and long-term durability.

1. Immediate Clarity on Strategy and Asset Focus

Within the first screen, a visitor should understand:

- What type of real estate the firm invests in

- Where it operates geographically

- How it deploys capital (funds, JVs, direct acquisitions, platforms)

Many real estate firms assume this is obvious. It rarely is — especially for multi-asset or multi-market platforms. If clarity requires scrolling or interpretation, the site is underperforming.

2. Clear Separation Between Firm, Strategy, and Assets

A common issue on real estate websites is structural blur. Firm-level positioning, strategy descriptions, and individual assets are often mixed together, making it difficult to understand how the platform actually works.

Best practice includes:

- A firm-level overview that explains the platform

- Dedicated strategy pages for each investment approach

- Asset or portfolio pages that support — but don’t define — the firm

The goal is to show how assets roll up into a coherent investment strategy, not to let the portfolio speak in isolation.

3. Strategy Pages That Explain How Capital Is Deployed

Real estate investors care as much about process as outcome.

Each strategy page should clearly articulate:

- Asset types and risk profile

- Typical deal size and capital structure

- Role of operating partners or in-house teams

- Where value is created (development, repositioning, operations, structuring)

Avoid generic language. Precision builds confidence.

4. Portfolio Presentation That Prioritizes Insight Over Volume

Large portfolio grids rarely communicate much beyond scale.

Effective portfolio sections:

- Curate assets selectively rather than exhaustively

- Highlight relevance (strategy, geography, thesis)

- Use concise descriptions that explain why an asset matters

By 2026, portfolio sections that feel indiscriminate or purely visual are easy to dismiss.

5. Team Pages That Signal Execution Capability

For real estate managers, team pages are especially important. LPs, partners, and sellers want to know who is actually executing deals and managing assets.

Strong team pages:

- Clearly distinguish leadership, investment, and operating roles

- Avoid résumé-style biographies

- Emphasize experience that aligns with strategy

The objective is confidence, not comprehensiveness.

6. Clear Positioning for Capital Partners and Counterparties

Real estate managers are evaluated by more than LPs.

The website should work equally well for:

- Institutional investors

- Joint venture partners

- Lenders

- Sellers and brokers

If the site only speaks to one audience, others are left to infer — and inference often leads to misinterpretation.

7. Messaging That Reflects the Current Platform, Not the Origin Story

Many real estate firms evolve quickly — new markets, new strategies, larger capital bases — but their websites lag behind.

Review the site for:

- Language that undersells scale or sophistication

- Strategy descriptions that no longer reflect how deals are done

- Positioning that assumes a single-market or single-asset focus

A website that reflects an earlier version of the firm creates friction rather than trust.

8. Durable Language That Doesn’t Depend on Market Cycles

Real estate is cyclical, but websites shouldn’t be.

Favor:

- How the firm approaches risk and execution

- Structural advantages rather than short-term performance claims

- Principles that hold across market environments

This reduces the need for constant rewrites as conditions change.

9. Design That Supports Structure and Readability

Design should make complex information easier to absorb.

Effective real estate sites prioritize:

- Clear hierarchy across pages

- Consistent layouts for strategies and assets

- Restraint in animation and visual effects

A site that looks polished but feels hard to navigate will not age well.

10. Performance, Security, and Accessibility as Baseline Requirements

By 2026, technical standards are table stakes.

Ensure:

- Fast load times across devices

- Secure hosting and regular updates

- Accessibility compliance

- A CMS that allows internal updates without breaking structure

These elements are rarely praised when done well — and immediately noticed when they aren’t.

11. Hosting and Maintenance Ownership Is Clearly Defined

A real estate website should not depend on a single vendor or individual.

Confirm:

- Who controls hosting and CMS access

- How updates are handled

- What maintenance is covered ongoing

Operational clarity prevents delays and dependency issues, particularly during active deal cycles.

12. Preparedness for AI-Assisted Reading

Increasingly, real estate manager websites are parsed by tools that summarize, compare, and extract meaning.

To support this:

- Use clear headings and structured content

- Avoid vague or purely aspirational language

- Make key facts explicit and easy to identify

- Implement backend schema and other AI optimization tools

Clarity benefits both human readers and systems.

13. Consistency Across All Firm Materials

The website should align with every other touchpoint, whether public-facing or shared privately.

This includes:

- Pitch decks and investment memos

- One-pagers and factsheets

- ESG reports, year-in-review pieces, and lender materials

Anyone who encounters the website should expect the same narrative, positioning, and visual system across all other materials.

14. Flexibility to Evolve Without a Full Rebuild

A well-built real estate website should accommodate:

- New markets or strategies

- Portfolio turnover

- Team growth

- Additional disclosures

If every change requires a redesign, the underlying structure is too rigid.

Final Thought: The Website as Infrastructure

By 2026, a real estate investment manager website should be treated as infrastructure — not a marketing exercise. It should reduce friction, answer common questions early, and support confidence across audiences without constant explanation.

Darien Group works with real estate investment managers to design and maintain websites that do exactly that — building narrative and visual systems that hold together as platforms grow, strategies evolve, and market conditions change.