.jpg)

Side Letters

Side Letters is a collection of essays, research, and analysis on how investment firms communicate with investors, management teams, and transaction partners. The focus is practical: how firms articulate value, build credibility, and navigate increasingly complex evaluation environments.

Featured Videos

Most emerging managers think design in a pitchbook is about aesthetics — color choices, layout, typography, the general look and feel. LPs don’t experience it that way. They don’t evaluate pitchbooks on beauty; they evaluate them on intent. Design becomes a form of pattern recognition: a quick way to assess whether the GP is organized, credible, and attuned to institutional expectations. Design is not the wrapper around the story. It is the first operational artifact an LP encounters, and it tells them far more than most managers realize.

1. Design Signals Whether the GP Understands the Institutional Environment

LPs have seen thousands of pitchbooks. They know what a mature deck looks like, and they know what an improvised one looks like. When a deck feels under-designed or oddly assembled — misaligned charts, inconsistent fonts, clashing iconography — LPs instinctively read that as a lack of institutional fluency. They don’t think, “This is ugly.” They think, “This manager hasn’t quite internalized the norms of our world.” That inference may be unfair, but it is reliable. Design is not just visual styling; it is an indicator of whether the GP knows the rules of the professional arena they’re entering.

Emerging managers sometimes underestimate this because they have worked in environments where someone else handled the brand infrastructure, and materials arrived pre-structured. When they go solo, they realize how much design literacy they had been absorbing subconsciously. LPs can tell when that literacy is missing.

2. Overdesign Is as Damaging as Underdesign

If one group of emerging managers errs on the side of minimalism, another group errs on the side of ornamentation — especially in real estate. They want the deck to look like a gorgeous property brochure because that’s what they’re used to seeing in the marketing of assets. But a glossy, hyper-stylized pitchbook does not communicate what a fund pitchbook needs to communicate. It doesn’t say, “We are serious stewards of institutional capital.” It says, “We know how to market assets,” which is a different skill entirely.

On the private equity side, overdesign appears in subtler ways: too many color gradients, heavy motion-like effects, fonts that feel like they belong in a consumer brand rather than in institutional finance. These are distractions, not advantages. LPs don’t want to think about design; they want design to make thinking easier.

Good design in a pitchbook is invisible. It creates clarity without calling attention to itself.

3. PowerPoint Is Not a Limitation — It Is an Expectation

Every now and then, a new manager will ask us to build their pitchbook in InDesign because they want it to look “more premium.” And yes, InDesign can produce beautiful documents. But these requests are almost always rooted in misunderstanding. LPs expect pitchbooks in PowerPoint because PowerPoint is editable, familiar, and legible in the context of diligence. A deck that is too glossy or too static can feel like it’s trying to compensate for something. LPs want substance, not spectacle. The format shouldn’t be the memorable part.

This is not to say pitchbooks should be plain. They should simply be aligned with what the category expects. In an emerging manager context, memorability should come from the ideas, not the packaging.

4. Consistency Across Materials Is a Signal of Organizational Maturity

LPs don’t evaluate your pitchbook in isolation. They triangulate it with your website, your bios, your data room, and even your email signature. When these elements are aligned, they signal discipline. When they are not, they signal drift. A pitchbook that looks one way while the website looks another forces the LP to reconcile two versions of the same firm. Most won’t bother.

This is especially true when the deck’s tone diverges from the website’s tone. If the deck is conservative but the website is modern, or the deck is overly technical while the digital presence is clean and straightforward, LPs interpret that inconsistency as a lack of self-understanding. In reality, the GP may simply be iterating quickly. But to LPs, it reads as fragmentation.

The pitchbook is where narrative and design converge most visibly. When it matches the rest of the firm’s digital ecosystem, LPs feel the underlying cohesion. When it doesn’t, they feel the instability.

5. Poor Design Doesn’t Make You Look Unattractive — It Makes You Look Unready

Emerging managers often think bad design will make them look unsophisticated. That’s not the real issue. Bad design makes you look unready. It signals that the GP has not taken the time to structure their story, their visual system, or their materials in a way that supports institutional evaluation. Even something as simple as a mismatched chart or a slide that feels “borrowed” from an old deck sends a quiet signal: this manager is still assembling themselves.

LPs may not consciously register these cues, but subconsciously they draw inferences: If the deck is disjointed, is the process disjointed? If the exhibits are sloppy, are the underwriting memos sloppy? If the narrative is unclear visually, is it unclear operationally? None of this is determinative. But all of it is suggestive.

Emerging managers underestimate how quickly these inferences form and how slowly they dissipate.

Closing Thought

Design in investor materials is not cosmetic. It’s structural. It shapes how LPs absorb your story, how they interpret your maturity, and how they assess your readiness for institutional capital. The goal is not to impress; the goal is to make the narrative unmistakably clear. When a pitchbook feels intentional, coherent, and appropriately restrained, LPs assume the same about the underlying firm. And for emerging managers, that assumption is often the bridge between being viewed as “interesting” and being viewed as “investable.”

There is a juncture in the life of a private equity firm that does not appear on the org chart or in the fundraising timeline, yet it carries enormous strategic weight. It arrives when the internal complexity of the firm surpasses the simplicity of the story it tells about itself.

We see this most clearly in firms that have evolved beyond a single investment style. They add new strategies, expand operator networks, pursue more creative transaction structures, or institutionalize their team. Internally, the firm becomes sharper and more sophisticated. Externally, it still communicates like the earlier version of itself.

The result is an informational mismatch.

This article examines the specific scenarios in which this happens and why the solution requires more than new language. It requires a restructured mental model of how the firm explains itself to the outside world.

1. The Multi-Strategy Drift: When a Firm Builds Two Engines but Describes Only One

A common pattern appears when a firm that built its reputation through platform investing adds a second engine. It might introduce:

- an asset-level solutions strategy

- a structured capital sleeve for operators

- a secondary program designed to purchase equity at a discount

- a co-investment structure that complements the core strategy

Inside the firm, these strategies share logic. They draw on the same operators, the same information pathways, or the same pattern recognition.

Outside the firm, they appear unrelated.

The typical scenario looks like this:

- A firm’s asset-level work depends on insights drawn from its platforms.

- Its platform work benefits from relationships created through solutions-oriented capital.

- Its team learns across strategies in ways that accelerate underwriting.

Yet the external materials describe these strategies in separate silos. The audience cannot see the relationships, so the firm appears more fragmented than it is.

This fragmentation is not a branding problem. It is an architectural problem.

2. The Operator-First Reality: When Your Competitive Advantage Is Invisible Externally

Many firms derive real advantage from their operator relationships. Operators provide early visibility into opportunities, real-time context on market conditions, and nuanced feedback that strengthens underwriting.

Yet this operator-centered model rarely appears in firm messaging. Instead, communication defaults to fund size, sector focus, and geography.

We often see a scenario like this:

A firm sources half its best opportunities from operators long before intermediaries circulate them. Its diligence processes rely on direct conversations with management teams who trust the firm’s approach. Its multi-year relationships lead to repeated opportunities within the same network.

But none of this shows up in the firm’s external explanations. The operator network is treated as incidental rather than central.

Once articulated clearly, this advantage reshapes how intermediaries engage, how operators reach out, and how LPs interpret the strategy. A firm is not differentiated by the existence of an operator network but by the meaning of that network within its investing model.

When the firm finally explains this clearly, the market recalibrates its understanding.

3. The Maturity Gap: When an Institutional Firm Communicates Like an Early-Stage Firm

As firms scale, they adopt new structures. They introduce investment committees, create value-creation frameworks, develop internal reporting cycles, and build differentiated roles across the team.

Yet externally, the firm may still present itself as a small specialist with a simple model.

This creates a misalignment with consequences:

- LPs cannot fully see the sophistication that now exists

- Operators underestimate the firm’s ability to support them

- Candidates misunderstand what the role will require

- Advisors send opportunities that do not match the evolved mandate

The firm operates at a higher level than its communication suggests. The gap between internal structure and external messaging becomes a source of inefficiency.

The firm is, in effect, outgrowing its own story.

4. The Understatement Paradox: When Restraint Collides With Institutional Expectations

Many firms prefer a restrained identity. They value discretion, focus, and a low-contrast style. They resist anything that feels promotional.

This preference is deeply rooted in the middle market.

However, restraint does not eliminate the need for clarity. It simply constrains the methods available to provide it.

We often hear something like this:

A firm wishes to remain understated while also wanting better recognition among operators, clearer articulation of its strategies, and materials that reflect its maturity.

This is not a contradiction.

It is a structural challenge.

Understated firms do not need more noise. They need sharper explanations. They benefit from organized information, precise framing, and communication that mirrors their temperament without diminishing their sophistication.

5. The Missing Framework: When Everything a Firm Says Is Correct but Not Connected

Many firms share accurate details about themselves. They describe sectors, strategies, geographies, team backgrounds, and values.

Yet what the audience is seeking is the foundational idea that connects these components.

For example:

- A firm may appear diversified across nine asset categories, when in reality its exposure reflects a highly focused operator sourcing model.

- A firm may appear geographically scattered, when in truth its operators create a unified map of where demand exists.

- A firm may appear to run unrelated strategies, when the strategies reinforce one another in ways that improve decision making.

The facts are sound. The interpretation is incomplete.

Without a framework that explains how the parts relate, the message relies on the audience to infer the structure, and most will not.

Conclusion. The Most Strategic Firms Rebuild Their Message When Their Structure Evolves

Private equity firms change. They implement new strategies, deepen relationships with operators, enhance internal processes, and refine their investment discipline. What often remains unchanged is the external message that once served the earlier version of the firm.

Eventually, the firm reaches a point where the old message obscures the current strategy. The organization becomes more sophisticated, but the communication remains static.

The firms that address this inflection point do not simply revise language. They reorganize how they explain themselves. They establish a structured foundation that accurately reflects the firm's actual design. They make the internal logic visible and accessible.

A firm that communicates its structure with precision is interpreted with precision. A firm that expresses its model clearly is understood quickly and accurately. A firm that reorganizes its message to match its evolution operates with fewer barriers and greater momentum.

Private equity and alternative investment firms often come to us at the exact moment when their brand foundation is starting to feel too narrow for where the firm is heading. In these early conversations, we hear a familiar mix of excitement and uncertainty. Some clients arrive with a few potential names already chosen. Others have no formal collateral at all. Most know exactly how they want to be perceived, but are unsure how to translate that into a name, identity, and digital presence that feels intentional, credible, and lasting.

These discussions often surface deeper strategic questions. How should a new firm position itself relative to its legacy. How do you craft a visual identity that feels distinct without drifting into abstraction. How do you build a website that supports fundraising and deal conversations at the same time. Over the years we have noticed patterns in how successful firms navigate these decisions.

This is a look behind the curtain at the conversations that shape a brand before any pixels or pages exist.

Why Naming Is a Strategic Exercise, Not a Creative Guessing Game

We have had many founders say something like, “We have three names we like. Can you tell us which one is strongest.” What they are really asking is whether their instincts align with how the market will interpret the name. We see this across nearly every naming engagement. The debate feels tactical, but the underlying questions are philosophical. What makes a name credible. What makes it durable. What will it signal in a room full of LPs or founders.

We have written before about how naming actually works in investment management, and why the search for the perfect name is often a distraction from the decisions that matter. Read more in our piece, The Myth of the Perfect Name in Investment Management.

Our own experience has shown that naming is not a subjective preference exercise. It is a strategic filter. The categories we explore during discovery determine the types of names that make sense for the firm. The name chosen should reflect how the firm wants to be understood by investors, founders, and partners for years to come.

The Branding Process Firms Respond to Most

Many private equity firms initially approach branding with a desire for speed. They quickly learn that momentum requires structure. When we outline a typical process, clients often say this is the first time branding has felt navigable.

The progression matters. Conversations during discovery shape the takeaways that inform early positioning. That positioning informs creative direction. That direction shapes the first versions of the homepage. Those prototypes give structure to the written narrative. Each step compounds the previous one and reduces revision cycles later.

Firms often tell us that this stage is where they finally see their story reflected back with clarity. The language begins to align with the identity they want to project. The early visuals define the posture they intend to occupy in the market. Branding is not a linear checklist. It is a sequence of calibrations.

How PE Firms Should Think About Website Strategy During a Brand Build

In nearly every early meeting, we hear a version of the same request. A firm needs a first-phase website ready for a capital conversation, or a homepage that can support active deal sourcing. The tension is familiar. Firms want the long-term brand to be thoughtful, but they also need something credible in the near term.

The solution is structured sequencing. We often begin with strategic website planning, even before the full identity is complete. This includes page hierarchy, story architecture, and functional planning. Once those decisions are aligned, we create an interactive prototype that lets the working group experience the site before development begins.

Clients consistently say this is one of the most clarifying steps. Seeing the site in motion, even in grayscale, helps them understand how the brand will behave digitally. It also compresses future revisions because structure, flow, and messaging are already aligned.

What Firms Can Prepare Before a Brand Engagement Begins

Some teams have a library of strategy decks and positioning language ready to share. Others have only a broad idea of how they want to present themselves. Both starting points are workable. What matters more is assembling the reference points that help tune early creative decisions.

Screenshots of sites they admire. A list of attributes they want the brand to convey. A few inspirational materials saved over the years. These clues provide direction for creative range finding and avoid unnecessary exploration.

More important is early access to leadership. Five or six hours of interviews across senior partners, junior team members, and operational leads often produces sharper insights than any written document. Those themes become the foundation of the brand.

The Less Visible Work That Ensures a Smooth Brand Build

Clients often assume the most challenging work lies in the creative expression. In reality, the leverage comes from the operational details. Clear working-group structure. Defined decision-making protocols. Predictable handoffs between strategy, design, and development. A shared Dropbox environment for materials. A scheduling process that eliminates friction.

When firms reflect on successful brand projects, they rarely point to a single deliverable. They point to the experience of the process. They describe predictability, clarity, and momentum.

What These Conversations Tell Us About Successful PE Branding Today

Private equity branding is changing. Firms value substance over theatrics. They want names that reflect intent. They want websites that guide LPs and founders toward meaningful conclusions. They want identities that feel modern and calibrated to their worldview. And they want narratives that reflect the seriousness of their work.

Early branding work often reveals the same underlying desire. Firms want a structure that helps them understand themselves with precision. A strong brand is not decoration. It is a framework for how a firm shows up in the world and the expectations it sets for its partners.

In recent years, we have seen a noticeable shift in how a subset of private equity firms chooses to present itself. While the broader market often rewards volume and visibility, many middle-market managers are taking the opposite route. These firms are opting for a quieter, more intentional brand strategy that mirrors how they operate and how they want to be perceived.

Their goal is not to reduce communication. Rather, it is to communicate with purpose. In an industry defined by relationships, the measured approach can be more effective than traditional forms of self-promotion.

1. Operators are responding to firms that present themselves as true partners

Across conversations with operators, a pattern consistently appears. They prefer investors who feel collaborative, approachable, and grounded in day-to-day realities. They are less interested in firms that rely on high-gloss positioning or the familiar language of financial prestige.

A quieter brand strategy sends a different signal. It tells operators that the firm values consistency over spectacle, clarity over flourish, and long-term partnership over transactional behavior. This aligns with what many operators say they want from their capital providers and often influences how they evaluate potential investment partners.

Quiet, in this sense, communicates steadiness.

2. A more restrained brand style helps firms stand out in a crowded middle market

Many middle-market firms struggle to express what makes them distinct. Their strategies, sector interests, and value creation processes often overlap. In this environment, louder communication does not guarantee recognition.

The firms choosing a quieter approach tend to explain their strategies with more precision. They describe their sourcing methods, their focus areas, and the reasoning behind their investment structures in ways that feel accessible and grounded. This simplicity clarifies their position in the market and gives the audience the context it needs to understand the firm’s strengths.

By reducing noise, they sharpen their message.

3. Firms with multiple strategies benefit from a clean, unified explanation of how they operate

Many firms now manage more than one strategy. Platform investing might sit alongside structured solutions, secondaries, or asset-level opportunities. While these approaches may connect internally, they often appear disjointed in external communication.

A quieter brand strategy forces firms to simplify how they explain their platform. Instead of presenting a collection of funds, they articulate a shared philosophy that underpins each strategy. They describe the operators they support, the types of situations they address, and the guiding principles that shape their work. This creates a sense of unity across the firm and allows audiences to understand how the parts fit together.

The approach does not reduce complexity. It organizes it.

4. Culture has become a practical differentiator but requires thoughtful expression

Firms regularly tell us that culture is one of their strongest attributes. They highlight lean teams, open communication, entrepreneurial mindsets, and a willingness to adapt. Yet these qualities often appear only in recruiting material or are expressed using generic language.

A quieter approach allows culture to emerge naturally. It highlights values through tone, through the way the firm describes its work, and through the emphasis placed on people rather than slogans. This helps the firm speak to operators, advisors, and potential hires in a way that reflects its actual working style.

When expressed honestly, culture becomes a competitive advantage.

5. Measured visibility performs better than high-frequency visibility

Many firms wrestle with a familiar tension. They want to be more widely known but do not want to resemble the more theatrical versions of private equity branding. They want materials that feel contemporary but not ostentatious. They want content that carries weight without becoming prolific.

This has led to a focus on selective communication. Firms are publishing fewer pieces, but each one is clearer. Their websites are structured for straightforward navigation rather than maximalist storytelling. Their materials highlight the essentials rather than an exhaustive list of details. Their tone is confident without being elevated for effect.

This form of visibility feels more aligned with how institutional audiences prefer to process information.

6. Quiet does not mean reserved. It means intentional.

The most effective understated brands share several traits. They organize information in a way that reduces friction. They communicate their approach in direct, plain language. They prioritize what the audience needs to know rather than everything the firm could say.

Quiet firms are not withholding details. They are arranging them with care.

This approach also mirrors how these firms behave in practice. They are selective about the situations they pursue. They build long-term relationships with operators. They maintain disciplined internal processes. Their communication strategy is simply an extension of how they work.

Conclusion. A quiet brand strategy can strengthen a firm’s position

For many private equity firms, especially those focused on long-term operator relationships and specialized middle-market strategies, a quieter brand posture aligns with their core identity. It allows them to present themselves in a way that feels accurate, thoughtful, and sustainable.

Quiet brands balance accessibility with professionalism. They emphasize clarity over ornamentation. They create space for the audience to understand the firm on its own terms.

Quiet is not absence. Quiet is structure. Quiet is careful expression. And for firms that succeed through depth rather than volume, it can be a meaningful strategic choice.

Private equity firms spend significant time refining their LP materials, yet founder-facing pitch decks are often treated as a secondary asset. In many cases, the same core presentation is reused across audiences with only minor adjustments. While this approach may feel efficient internally, it rarely aligns with how founders actually evaluate potential partners.

The result is not a lack of professionalism or effort, but a mismatch between intent and impact. Founder pitch decks frequently fail not because they are poorly designed, but because they are built for the wrong audience.

Why Founder Audiences Are Different

Founders do not approach a first meeting with a private equity firm as a financial exercise alone. While financial outcomes matter, the initial evaluation is more qualitative. Founders are assessing whether a firm understands their business, respects the complexity of what they have built, and has a credible perspective on the company’s future.

LP decks are designed to demonstrate discipline, track record, and process. Founder decks must do something else entirely. They need to communicate alignment, judgment, and long-term intent. When firms rely on institutional materials to do that work, the message often falls flat.

The Hidden Gap Between Conversation and Materials

One of the most common issues with founder pitch decks is internal inconsistency. Partners and senior team members tend to lead conversations with a set of themes that feel natural and compelling in person. These points emerge through experience—what resonates, what differentiates the firm, and what founders respond to over time.

However, those themes are often absent from the written materials. Decks become static documents that lag behind how the firm actually presents itself in meetings. Over time, a gap forms between what is said and what is shown. While this disconnect may not be obvious internally, it is immediately apparent to founders encountering the firm for the first time.

What Founder Pitch Decks Are Actually Meant to Do

A founder pitch deck is not meant to be comprehensive. Its purpose is not to explain every capability or document every investment outcome. Instead, it should create clarity around how the firm thinks, how it operates, and what kind of partner it intends to be.

Effective founder decks prioritize narrative over volume. They focus on a small number of ideas that matter and articulate them clearly. Rather than listing services or value creation initiatives, they frame a point of view—about growth, ownership transitions, and partnership dynamics—that founders can engage with.

Rethinking Case Studies for Founder Audiences

Case studies are often included in founder decks, but rarely in a form that serves their intended audience. Traditional case study formats tend to mirror banker materials, emphasizing transaction details and financial metrics. While those elements have their place, they do little to address the questions founders are actually asking.

Founders want to understand how decisions were made, how challenges were handled, and how the relationship between investor and management team evolved over time. Case studies that highlight these qualitative dimensions are more effective, particularly when they are designed to be modular and adaptable across different contexts.

Design as a Supporting Element, Not the Story

Design plays an important role in founder pitch decks, but it is not the differentiator. The most effective decks strike a balance between polish and practicality. They feel current and intentional without appearing overproduced, and they remain fully editable for internal teams.

When design works, it reinforces the narrative rather than distracting from it. It helps structure the conversation, guide attention, and create a sense of cohesion across the materials.

Narrow Engagements Can Drive Meaningful Change

Many firms assume that improving founder materials requires a broad brand initiative. In practice, focused engagements often deliver the most value. A well-structured founder deck, supported by a flexible template and a small set of strong case studies, can significantly improve how a firm is perceived in early conversations.

These projects also tend to surface deeper messaging questions, creating a natural foundation for future work without requiring an immediate, all-encompassing commitment.

A Better Question to Ask Internally

Rather than asking whether a founder deck looks professional, firms should ask whether it accurately reflects how they think and how they speak. If the materials do not capture the firm’s real perspective, founders will sense that disconnect quickly.

Clarity, consistency, and intention matter more than volume. When founder pitch decks are built with those principles in mind, they become a meaningful part of the relationship-building process rather than a formality to get through.

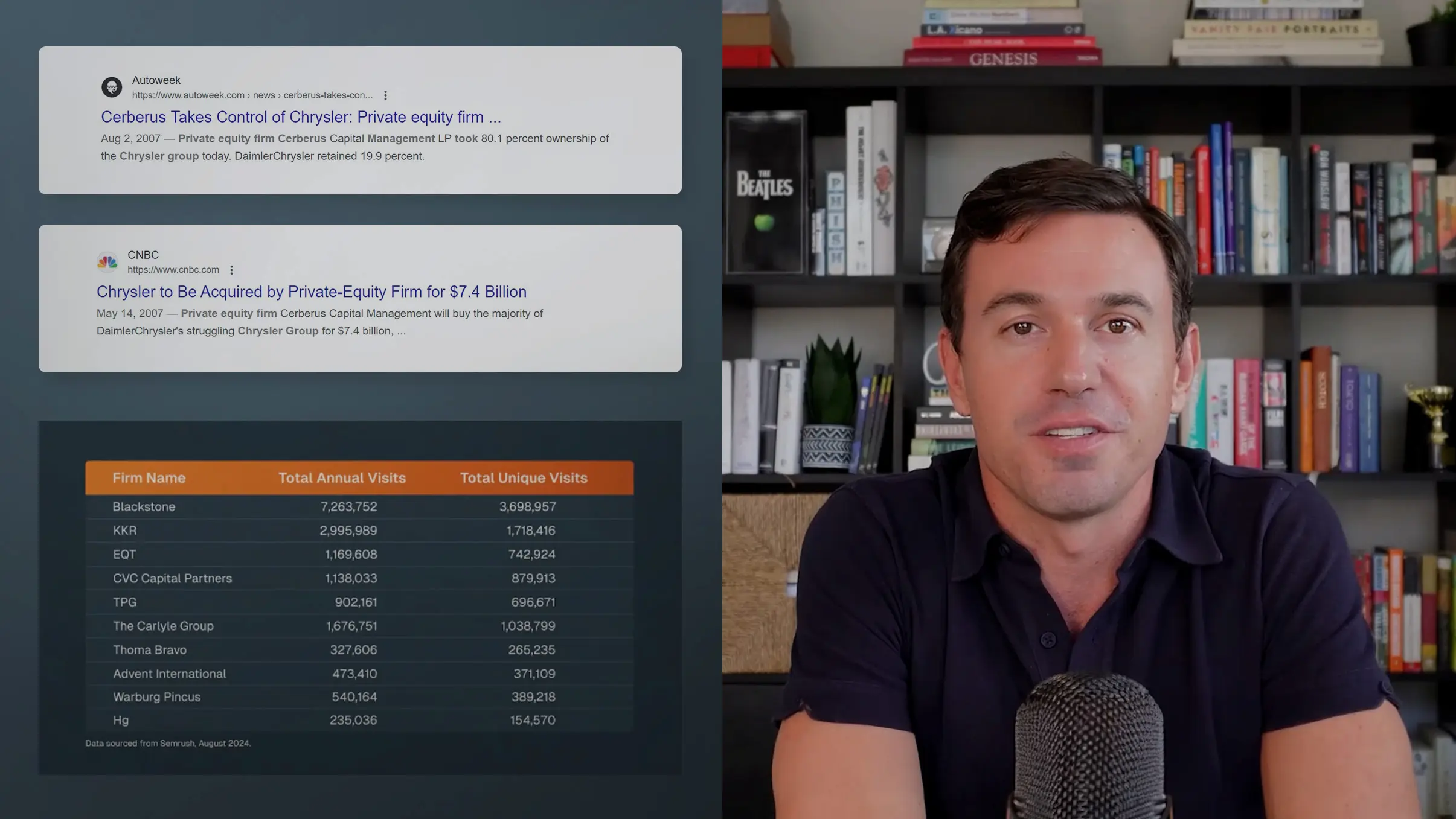

A Practical Perspective on Private Equity Digital Marketing and Thought Leadership

LinkedIn has quietly become one of the most influential digital channels in private equity. It is the only environment where LPs, founders, intermediaries, operating leaders, and potential hires all spend meaningful time in the same ecosystem. Yet it is also the channel the industry uses least effectively.

Most firms treat LinkedIn as an announcement board. Others ignore it entirely. Only a small number use it as a strategic tool for shaping how the market perceives their expertise long before a fundraising meeting or sourcing conversation takes place.

For those firms, LinkedIn is not a visibility tool. It is a memory tool. It reinforces the firm’s thinking at a cadence the market can absorb, with none of the constraints of more formal communication channels.

The Most Valuable Content Is the Content You Already Have

Many private equity firms assume they need to create new content in order to publish regularly. In reality, most already produce more high-quality thinking than they realize.

AGM decks, quarterly letters, white papers, investment committee themes, diligence observations, and even partner conversations often contain insights that can be repurposed into LinkedIn posts with very little friction. One substantial memo can support an entire week of content. One conference panel can yield three or four thoughtful angles.

But not every firm has formal materials. Some have intellectual depth but limited documentation. That is not a barrier. In those cases, the content simply lives in conversation rather than in writing.

Short internal interviews, recorded partner Q&A sessions, and structured prompts about sector themes or market behavior can produce a deep pipeline of ideas. The value is already there. It just needs to be captured and formatted.

For private equity, the hard part is not creativity. It is conversion. LinkedIn success is about translating insight, not inventing it.

LinkedIn Is Not Hard. Prioritizing It Is.

The most common obstacle is not lack of perspective. It is lack of time.

Deal cycles, fundraising, quarterly reporting, and portfolio needs push LinkedIn to the margins. Most teams start strong, publish a few posts, then disappear for weeks because the operational burden was never addressed.

LinkedIn programs collapse not for strategic reasons but for logistical ones.

A sustainable private equity LinkedIn strategy replaces improvisation with process.

It creates a system for:

- sourcing ideas

- repackaging material the firm already has

- designing repeatable templates

- scheduling posts weeks ahead

- maintaining consistency even when the team is deep in deal work

The ideas already exist.The work is organizing them into a cadence that the team can sustain.

Where LinkedIn Fits in the Private Equity Marketing Mix

LinkedIn is not a substitute for investor letters, conference participation, or direct LP conversations. It is a complement. It ties together the firm’s public presence, investor communication, and thought leadership in a cohesive rhythm.

It is not the most targeted channel in private equity. It will never replace the relationship-driven work that defines the industry.

What it does offer is something rare in PE: a low-effort, high-frequency channel that compounds.

Used well, LinkedIn allows a firm to:

- extend the reach of content it already produces

- reinforce its point of view between meetings

- remain visible to LPs, founders, bankers, and talent without being intrusive

- build audience memory one post at a time

Used poorly, it becomes a sporadic news feed. The firms that benefit are the ones that treat LinkedIn as an ongoing narrative, not an announcement channel.

Formats That Actually Work for Private Equity

LinkedIn rewards consistency and clarity over theatrics. Private equity firms do not need to chase trends. They need to choose formats that align with how their audience learns.

Effective formats include:

- short observations drawn from research or sector work

- carousel slides that simplify a complex concept

- commentary on relevant industry news with an actual point of view

- repurposed AGM or portfolio insights

- occasional long form posts that articulate the firm’s philosophy

The variety is intentional. Different audiences engage with different formats, and LinkedIn’s algorithm responds to mixed content far more strongly than repetitive formats.

Why LinkedIn Matters More Than Most Firms Realize

Private equity is a long memory business. Deals, diligence, fundraising, and relationship building often unfold over months or years. LinkedIn is one of the few platforms where firms can create consistent familiarity with minimal bandwidth.

A prospective LP may not remember every detail from a meeting, but they will recognize a firm that appears regularly in their feed with thoughtful insights. A founder may not respond to the first outreach, but repeated exposure builds comfort. Bankers recall firms that demonstrate clarity of thought.

LinkedIn does not create relationships. It accelerates them.

The Role of a Specialized Partner

Executing a structured LinkedIn strategy requires a blend of capabilities that is uncommon inside most private equity firms. The partner must understand investment strategy, LP sensibilities, founder psychology, and how to translate technical content into formats that perform on LinkedIn.

A capable partner helps the firm:

- identify and extract content that already exists

- build a sustainable posting cadence

- design templates that maintain consistency

- repurpose materials without diluting nuance

- manage the operational lift so the team can stay focused on investment work

LinkedIn success in private equity is not defined by frequency or flair. It is defined by judgment, structure, and the ability to express ideas clearly at scale.

The New Competitive Edge

The private equity firms that will stand out over the next decade are not the ones that publish the most. They are the ones that publish consistently, coherently, and credibly.

LinkedIn is becoming the place where firms teach the market how to think about them. The firms that begin now will build the kind of long horizon familiarity that cannot be manufactured later.

In a relationship-driven industry, that familiarity is not cosmetic. It is strategic.